History of secularism in France

In the 19th century, secularization laws gradually freed the State from its historical ties with the Catholic Church and created new political and social norms based on the principle of republican universalism.

This process, part of a broader movement associated with modernity, entrusted the sovereign populace with the redefinition of political and social foundations—such as legislative power, civil rites, and the evolution of law and morality—independently of any religious dogma.

[5] For Jean-Michel Ducomte, professor of public law, secularism, far from finding its source in religion, "is first and foremost a process of emancipation from the pretensions of the Churches to found the social and political order".

[6] Historian Georges Weill distinguishes four currents that contributed to the secular conception of the State:[7] "Catholics, heirs to the Gallican tradition of the Ancien Régime monarchy; liberal Protestants; deists of all persuasions; and freethinkers and atheists".

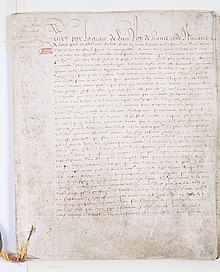

[10] Between the 15th and 16th centuries, Gallicanism was formalized in a series of texts (notably the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges) that affirmed the theological and legal dependence of the French Church on the State, and the superiority of royal power over the Papacy.

However, it was tempered in 1516 by the Concordat of Bologna, signed between King Francis I and Pope Leo X, which allowed widespread royal control over episcopal and abbatial appointments, giving rise to the commendation system.

To a certain extent (notably excluding Jews), it guaranteed freedom of religious conscience throughout the kingdom, allowing Protestants to worship freely in places where they had established communities prior to 1597.

Although the term itself is more recent, the philosophical and political idea of secularism appeared in England at the end of the 17th century, with King James II's notion of "indulgence" as universal freedom of conscience.

Voltaire, an admirer of Locke and Newton who had also contributed to the Glorious Revolution, wrote his Traité sur la Tolérance (Treatise on Toleration) on the occasion of the trial of Jean Calas, in which he argued that the political order could do without religious constraints, as did Montesquieu in De l'Esprit des Lois (The Spirit of Law).

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in Du contrat social, expounded on the concept of popular sovereignty and the notion of general interest, asserting that individuals must consent to surrender part of their "natural rights" for the benefit of the collective.

In 1766, the Chevalier de La Barre was condemned to ordinary and extraordinary torture, which included having his fist and tongue cut off, followed by decapitation and the burning of a copy of Voltaire 's Dictionnaire philosophique found in his home.

At the instigation of Louis XVI, Malesherbes published his Mémoire sur le mariage des protestants in 1785,[16] and in 1787 pushed through the Édit de Tolérance (Edict of Tolerance),[17] which organized the civil status of non-Catholics, thus initiating the beginning of legal recognition of the plurality of mores stemming from different faiths.

When the Constituent Assembly was formed, the starting point of the French Revolution, the clergy joined forces with the Third Estate and voted with them for the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of August 26, 1789.

Although inciting de-Christianization through the action of certain representatives on mission, the Revolution remained alien to the notion of secularism and wished to preserve the idea of basing the country's unity on a national religion.

[...] Anyone who violently disturbs the ceremonies of any religion, or outrages its objects, will be punished.This decree allowed churches - some of which had been transformed into temples of Reason, or even warehouses - to reopen, marking the end of repression of religious expression.

An organic law of 18 Germinal An X (April 8, 1802), intended to clarify the terms of the Concordat, further limited the Pope's role by reaffirming Louis XIV 's charter of the Gallican Church and restricting the freedom of movement of bishops, who were forbidden to assemble.

This document, which condemns the principles of secularism acquired since the French Revolution, states in particular:Each man is free to embrace and profess the religion he has deemed true according to the light of reason.

The condemnation of liberal Catholicism, freedom of the press and the revolutions of 1830 by the encyclical Mirari Vos[35] gave rise to what came to be known as the modernist crisis among many Catholics, and prompted governments to take retaliatory measures, including the German Kulturkampf (1864) and its Swiss counterpart (1873).

That same year, Leo XIII called for a rapprochement between Catholics and republicans in his encyclical letter Nobilissima Gallorum Gens,[n 3] lamenting that France had "forgotten its traditions and its mission".

Léon Gambetta declared:We must drive back the enemy, clericalism, and bring the layman, the citizen, the scholar, the Frenchman, into our educational establishments, raise schools for him, create teachers, masters.In the last quarter of the 19th century, France achieved a notable literacy rate, with 72% of newlyweds able to sign the marriage register.

Jules Ferry, a lawyer with a passion for public affairs and a sincere republican streak, radically reformed the school system of the Third Republic, making him an emblematic figure of French secularism.

His influence can be seen in the following stages: In February 1880, ecclesiastics were excluded from the Conseil supérieur de l'Instruction publique; in March, Catholic teaching was excluded from university juries and congregations were asked to leave their teaching institutes (Jesuits, Marists, Dominicans, Assumptionists); in December, Camille Sée passed a law creating colleges and lycées for girls; in June 1881, Paul Bert, former Minister of Public Instruction during the brief Gambetta government, reported that primary education was to become free.

Without doubt, its primary aim was to separate the school from the Church, to ensure freedom of conscience for both teachers and pupils, and to distinguish between two domains that had been confused for too long: that of beliefs, which are personal, free and variable, and that of knowledge, which everyone admits is common and indispensable to all.

But there's more to the March 28 law: it expresses our determination to found a national education system, and to base it on the notions of duty and right, which the legislator does not hesitate to include among the first truths that no one can ignore.

During the summer of 1904, a series of measures were taken to combat the influence of the Church: the de-naming of streets bearing the name of a saint, the closure of 2,500 religious schools, the systematic promotion of anti-clerical civil servants and the dismissal of Catholics.

Supporters of secularism were divided into two camps: the first, in the Jacobin tradition, hoped to eradicate the hold of religion on the public sphere, and promoted a clearly anticlerical (Émile Combes) or even anti-religious (Maurice Allard) policy; the second wanted to affirm the neutrality of the State, on the one hand, and guarantee freedom of conscience for everyone, on the other.

Generally well received by Jews and Protestants (including Wilfred Monod), the law was opposed by Pope Pius X, notably in his encyclical Vehementer Nos:[50]That it is necessary to separate the State from the Church is an absolutely false thesis, a very pernicious error.

[n 6] Bishop Louis Duchesne referred to this encyclical as Digitus in Oculo ("finger in the eye"), indicating that some members of the French clergy and laity had accepted the principles of secularism.

However, local authorities are required to provide housing for ministers of religion, to cover any budget shortfalls of the public establishment and to contribute to the financing of construction or major repairs to places of worship.

After being called into question under the Vichy regime (which favored Catholic education, recognized congregations and subsidized private schools), the secular nature of the State was affirmed in the 1946 and 1958 Constitutions.