History of sound recording

Many pioneering attempts to record and reproduce sound were made during the latter half of the 19th century – notably Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville's phonautograph of 1857 – and these efforts culminated in the invention of the phonograph by Thomas Edison in 1877.

These recorders typically used a large conical horn to collect and focus the physical air pressure of the sound waves produced by the human voice or musical instruments.

A sensitive membrane or diaphragm, located at the apex of the cone, was connected to an articulated scriber or stylus, and as the changing air pressure moved the diaphragm back and forth, the stylus scratched or incised an analog of the sound waves onto a moving recording medium, such as a roll of coated paper, or a cylinder or disc coated with a soft material such as wax or a soft metal.

Sound recording now became a hybrid process — sound could now be captured, amplified, filtered, and balanced electronically, and the disc-cutting head was now electrically powered, but the actual recording process remained essentially mechanical – the signal was still physically inscribed into a wax master disc, and consumer discs were mass-produced mechanically by stamping a metal electroform made from the wax master into a suitable substance, originally a shellac-based compound and later polyvinyl plastic.

The Western Electric system greatly improved the fidelity of sound recording, increasing the reproducible frequency range to a much wider band (between 60 Hz and 6000 Hz) and allowing a new class of professional – the audio engineer – to capture a fuller, richer, and more detailed and balanced sound on record, using multiple microphones connected to multi-channel electronic amplifiers, compressors, filters and mixers.

This device typically consists of a shallow conical diaphragm, usually of a stiff paper-like material concentrically pleated to make it more flexible, firmly fastened at its perimeter, with the coil of a moving-coil electromagnetic driver attached around its apex.

When an audio signal from a recording, a microphone, or an electrified instrument is fed through an amplifier to the loudspeaker, the varying electromagnetic field created in the coil causes it and the attached cone to move backwards and forward, and this movement generates the audio-frequency pressure waves that travel through the air to our ears, which hear them as sound.

Magnetic tape fueled a rapid and radical expansion in the sophistication of popular music and other genres, allowing composers, producers, engineers and performers to realize previously unattainable levels of complexity.

CDs are small, portable and durable, and they could reproduce the entire audible sound spectrum, with a large dynamic range (~96 dB), perfect clarity and no distortion.

Because CDs were encoded and read optically, using a laser beam, there was no physical contact between the disc and the playback mechanism, so a well-cared-for CD could be played over and over, with absolutely no degradation or loss of fidelity.

The uploading and downloading of large volumes of digital media files at high speed was facilitated by freeware file-sharing technologies such as Napster and BitTorrent.

In the field of consumer-level digital data storage, the continuing trend towards increasing capacity and falling costs means that consumers can now acquire and store vast quantities of high-quality digital media (audio, video, games and other applications), and build up media libraries consisting of tens or even hundreds of thousands of songs, albums, or videos — collections which, for all but the wealthiest, would have been both physically and financially impossible to amass in such quantities if they were on 78 or LP, yet which can now be contained on storage devices no larger than the average hardcover book.

To make this process as efficient as possible, the diaphragm was located at the apex of a hollow cone that served to collect and focus the acoustical energy, with the performers crowded around the other end.

Edison's invention of the phonograph soon eclipsed this idea, and it was not until 1887 that yet another inventor, Emile Berliner, actually photoengraved a phonautograph recording into metal and played it back.

Rather than using rough 19th-century technology to create playable versions, they were scanned into a computer and software was used to convert their sound-modulated traces into digital audio files.

The stylus vibration was at a right angle to the recording surface, so the depth of the indentation varied with the audio-frequency changes in air pressure that carried the sound.

The sound could be played back by tracing the stylus along the recorded groove and acoustically coupling its resulting vibrations to the surrounding air through the diaphragm and a so-called amplifying horn.

When entertainment use proved to be the real source of profits, one seemingly negligible disadvantage became a major problem: the difficulty of making copies of a recorded cylinder in large quantities.

Still, a single take would ultimately yield only a few hundred copies at best, so performers were booked for marathon recording sessions in which they had to repeat their most popular numbers over and over again.

The spiral groove on the flat surface of a disc was relatively easy to replicate: a negative metal electrotype of the original record could be used to stamp out hundreds or thousands of copies before it wore out.

The first electronically amplified record players reached the market only a few months later, around the start of 1926, but at first, they were much more expensive and their audio quality was impaired by their primitive loudspeakers; they did not become common until the late 1930s.

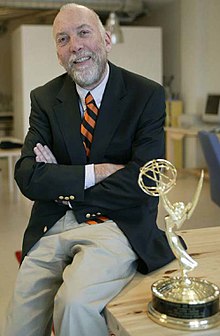

American audio engineer John T. Mullin served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps and was posted to Paris in the final months of World War II.

Mullin's unit soon amassed a collection of hundreds of low-quality magnetic dictating machines, but it was a chance visit to a studio at Bad Neuheim near Frankfurt while investigating radio beam rumors that yielded the real prize.

By luck, Mullin's second demonstration was held at MGM studios in Hollywood and in the audience that day was Bing Crosby's technical director, Murdo Mackenzie.

He had asked NBC to let him pre-record his 1944–45 series on transcription discs, but the network refused, so Crosby had withdrawn from live radio for a year, returning for the 1946–47 season only reluctantly.

Much of the credit for the development of multitrack recording goes to guitarist, composer and technician Les Paul, who also helped design the famous electric guitar that bears his name.

This led to a number of attempts to reduce tape hiss through the use of various forms of volume compression and expansion, the most notable and commercially successful being several systems developed by Dolby Laboratories.

The Dolby systems were very successful at increasing the effective dynamic range and signal-to-noise ratio of analog audio recording; to all intents and purposes, audible tape hiss could be eliminated.

In the late 1950s, the cinema industry, desperate to provide a theatre experience that would be overwhelmingly superior to television, introduced widescreen processes such as Cinerama, Todd-AO and CinemaScope.

The ADAT machine, followed by the Tascam equivalent, the DA-88, using a smaller Hi-8 video cassette, was a common fixture in professional and home studios around the world until approximately 2000 when it was supplanted by various interfaces and 'DAWs' (digital audio workstations) which allowed a computer's hard drive to be the recording medium..