History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

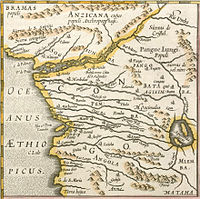

[1] The Atlantic slave trade occurred from approximately 1500 to 1850, with the entire west coast of Africa targeted, but the region around the mouth of the Congo suffered the most intensive enslavement.

Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba tried to suppress secession with the aid of the Soviet Union as part of the Cold War, causing the United States to support a coup led by Colonel Joseph Mobutu.

The report of the British Consul Roger Casement led to the arrest and punishment of white officials who had been responsible for cold-blooded killings during a rubber-collecting expedition in 1900, including a Belgian national who caused the shooting of at least 122 Congolese natives.

The interests of the government and private enterprise became closely tied; the state helped companies break strikes and remove other barriers imposed by the indigenous population.

[8] The country was split into nesting, hierarchically organized administrative subdivisions, and run uniformly according to a set "native policy" (politique indigène)—in contrast to the British and the French, who generally favored the system of indirect rule whereby traditional leaders were retained in positions of authority under colonial oversight.

Large numbers of white immigrants who moved to the Congo after the end of World War II came from across the social spectrum, but were nonetheless always treated as superior to blacks.

While there were no universal criteria for determining évolué status, it was generally accepted that one would have "a good knowledge of French, adhere to Christianity, and have some form of post-primary education.

[14] Since opportunities for upward mobility through the colonial structure were limited, the évolué class institutionally manifested itself in elite clubs through which they could enjoy trivial privileges that made them feel distinct from the Congolese "masses".

[20] That year the association was taken over by Joseph Kasa-Vubu, and under his leadership, it became increasingly hostile to the colonial authority and sought autonomy for the Kongo regions in the Lower Congo.

[22] The Belgian government was not prepared to grant the Congo independence and even when it started realizing the necessity of a plan for decolonization in 1957, it was assumed that such a process would be solidly controlled by Belgium.

[28] In October 1958 a group of Léopoldville évolués including Patrice Lumumba, Cyrille Adoula and Joseph Iléo established the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC).

[29] The MNC drew most of its membership from the residents of the eastern city of Stanleyville, where Lumumba was well known, and from the population of the Kasai Province, where efforts were directed by a Muluba businessman, Albert Kalonji.

[30] Belgian officials appreciated its moderate and anti-separatist stance and allowed Lumumba to attend the All-African Peoples' Conference in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958 (Kasa-Vubu was informed that the documents necessary for his travel to the event were not in order and was not permitted to go[31]).

The party advocated for a strong unitary state, nationalism, and the termination of Belgian rule and began forming alliances with regional groups, such as the Kivu-based Centre du Regroupement Africain (CEREA).

[36] Though the Belgians supported a unitary system over the federal models suggested by ABAKO and CONAKAT, they and more moderate Congolese were unnerved by Lumumba's increasingly extremist attitudes.

With the implicit support of the colonial administration, the moderates formed the Parti National du Progrès (PNP) under the leadership of Paul Bolya and Albert Delvaux.

[38] Following the riots in Leopoldville (4–7 January 1959) and in Stanleyville (31 October 1959), the Belgians realised they could not maintain control of such a vast country in the face of rising demands for independence.

Beginning in 1964, in the east of the country, Soviet and Cuban backed rebels called the Simbas rose up, taking a significant amount of territory and proclaiming a communist "People's Republic of the Congo" in Stanleyville.

[43] Unrest and rebellion plagued the government until November 1965, when Lieutenant General Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, by then commander in chief of the national army, seized control of the country and declared himself president for the next five years.

Embarking on a campaign of cultural awareness, President Mobutu renamed the country the "Republic of Zaire" in 1971 and required citizens to adopt African names and drop their French-language ones.

Although Mobutu successfully maintained control during this period, opposition parties, most notably the Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS), were active.

The conference gave itself a legislative mandate and elected Archbishop Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya as its chairman, along with Étienne Tshisekedi, leader of the UDPS, as prime minister.

The ensuing stalemate produced a compromise merger of the two governments into the High Council of Republic-Parliament of Transition (HCR-PT) in 1994, with Mobutu as head of state and Kengo Wa Dondo as prime minister.

There were reports that the conflict is being prolonged as a cover for extensive looting of the substantial natural resources in the country, including diamonds, copper, zinc, and coltan.

A survey conducted in 2009 by the ICRC and Ipsos shows that three-quarters (76%) of the people interviewed have been affected in some way–either personally or due to the wider consequences of armed conflict.

After the results were announced on 9 December, there was violent unrest in Kinshasa and Mbuji-Mayi, where official tallies showed that a strong majority had voted for the opposition candidate Étienne Tshisekedi.

[69] The political allies of former president Joseph Kabila, who stepped down in January 2019, maintained control of key ministries, the legislature, judiciary and security services.

In April 2012, the leader of the CNDP, Bosco Ntaganda and troops loyal to him mutinied, claiming a violation of the peace treaty and formed a rebel group, the March 23 Movement (M23), which was believed to be backed by Rwanda.

[78] Since 2017, fighters from M23, most of whom had fled into Uganda and Rwanda (both were believed to have supported them), started crossing back into DRC with the rising crisis over Kabila's extension of his term limit.

[108] After disagreements over negotiating with the government and the killing of CODECO's leader, Ngudjolo Duduko Justin, in March 2020, the group splintered and violence spread into new areas.