History of the Jews in Atlanta

The community was deeply impacted by the Leo Frank case in 1913–1915, which caused many to re-evaluate what it meant to be Jewish in Atlanta and the South, and largely scarred the generation of Jews in the city who lived through it.

In 1958, one of the centers of Jewish life in the city, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, known as The Temple, was bombed because of its rabbi's support for the Civil Rights Movement.

Unlike decades prior when Leo Frank was lynched, the bombing spurred an outpouring of support from the broader Atlanta community.

[1] By 1850, 10% of Atlanta stores were run by Jews, who only made up 1% of the population[3] and largely worked in retail, especially in the sale of clothing and dry goods.

[2] The community was also very present in politics – two Jews from the Atlanta area were elected to the state legislature in the late 1860s and early 1870s, and in 1875 Aaron Haas was the city's mayor pro tem.

In 1887, Congregation Ahavath Achim was founded to fit this new portion of the community, and in 1901 their synagogue was built in the middle of the south side area where most Yiddish-speaking Jews lived.

In one such instance, the local Jewish paper remarked, "we want to make good American citizens out of our Russian brothers" and called the Yiddish speaking immigrants "ignorant."

It was not until the Great Depression that the Standard Club stopped discriminating on this basis, and by and large, it was not until World War II that the barriers between German and Yiddish Jews fell.

The Federation was (and remains) the umbrella organization for funding the community's institutions and charitable programs, while the Hebrew Orphans' Home served nearly 400 children in the first 25 years, later transitioning toward aiding foster care and supporting widows, and ultimately closing in 1930.

The case quickly became a major story in Atlanta, and the death brought tensions about child labor and the grievances of the rural working class to the fore, increasing pressure for someone to be held responsible.

[8][7] As to the atmosphere that led to Frank's prosecution, historian Nancy MacLean said it "[could] be explained only in light of the social tensions unleashed by the growth of industry and cities in the turn-of-the-century South.

"[9] Meanwhile, Frank's trial received full coverage in Atlanta's three competing newspapers, and public outrage only continued to grow over the murder.

The case was then appealed by his lawyers at every level, and it was during this time that Frank's plight became national news and galvanized the Jewish community across the country.

[2] The focus then largely shifted onto progressive and popular Georgia Governor John Slaton, then in his last days in office, to commute the death sentence.

[11] The case has been called the "American Dreyfus affair", as both centered around falsely accused wealthy assimilated Jewish men whose trials, based on minimal evidence, were the catalysts of anti-Semitic fervor in the masses which then led to their convictions.

[10] Even over 100 years later, the subject remains a touchy one for some, and how important what happened to Leo Frank is in the broader history of the Jewish community in Atlanta is still an open question.

Others in the community assign more lasting importance to what happened, and continue to call for political action to absolve and remember Frank, who in 1986 received a posthumous pardon based on the state's culpability in his death, rather than his innocence.

It was not until the 1920s that support for Zionism began to grow in the community, although there were a few small, frequently inactive Zionist organizations that started years prior.

A gathering celebrating the Allies of World War I’s support for a “Jewish national home” in Palestine at the San Remo conference amassed over 2,000 people in 1920.

This idea, however, was problematic as Rabbi Marx held very liberal Reform views, and was primarily representative only of the smaller but established and influential German Jewish community.

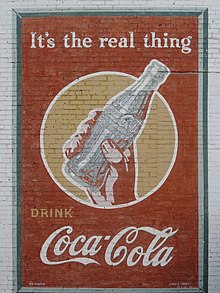

[15] Rabbi Geffen sought permission to view Coca-Cola's closely guarded secret formula in order to assess whether it could be deemed kosher, and was eventually granted it after being sworn to secrecy.

When he took over leading the synagogue, it was in a time when its membership and community had a growing fracture between its older, founding, Yiddish-speaking immigrants and the less traditional English-speaking next generation.

Gradually, changes were implemented in the synagogue, such as the women's section, which went from being in the balcony to part of the sanctuary floor, and eventually was eliminated in favor of mixed gender seating.

[2] Under the 51-year tenure of Rabbi David Marx, the members of The Temple were used to the idea that if it wanted acceptance, it could not afford to rock the boat in non-Jewish/Christian Atlanta society or cause conflict.

Not long after the explosion, United Press International (UPI) staff received a call from “General Gordon of the Confederate Underground”, a white supremacist group saying they carried out the bombing, that it would be the last empty building they bomb, and Jews and African Americans were aliens in the U.S.[19] The damage to the synagogue was estimated at $100,000,[18] or roughly $868,000 today adjusted for inflation.

The editor of the Atlanta Constitution newspaper, Ralph McGill, wrote a powerful editorial in the paper denouncing the bombing and any tolerance for hatred in the city, for which he won a Pulitzer Prize.

The sweeping outpouring of support and sympathy from the broader Atlanta society, and the swift action taken by officials, showed that they could feel secure now, decades after what happened to Leo Frank.

[17] At the same time, for many in the African American community, the public and official reactions to the bombing were deeply frustrating, as such terror was inflicted on them more frequently and without support or effective investigations.

Responding to Ralph McGill's piece about the bombing, the daughter of slain Florida NAACP director Henry T. Moore lamented the lack of similar outcry or care on the part of the government at the state or federal levels in investigating the crime.

When Jimmy Carter, who had been Governor of Georgia, was elected President in 1976 several Atlanta Jews such as Stuart E. Eizenstat and Robert Lipshutz moved to Washington with him to work in the administration.