History of the Jews in Leipzig

[3] The first documentation of the existence of a Jewish community within Leipzig came from a collection of responsa between 1250 and 1285 that was compiled by Rabbi Yitshak ben Moshe of Vienna, the famous Isaac Or Zarua or Riaz.

[1] The documentation of his answer to the dispute indicated that the Jews of Leipzig already had a synagogue at this time, and their main source of income appeared to come from finance.

Starting with a ban on public prayers within synagogues, the regulations reached a radical peak in 1430, when the Jews of Leipzig were expelled from Saxony, and their property was also confiscated.

[4] As Jews were, for the most part, only allowed short stays in the city between the 16th and 18th century, a permanent Jewish community was virtually non-existent.

[8] Due to the overwhelming number of Jews temporarily staying in Leipzig during fair periods, many merchants established prayer rooms.

Jews were once again allowed to hold public prayer services, and in 1815 the municipal council agreed to open Leipzig's first Jewish cemetery.

Several Antisemitic newspapers began to appear around this time, and the frequency of targeted harassment and discrimination against Jews increased.

[4] During this peak in the Jewish population, many Leipzig Jews were members of the upper-middle-class, which included businessmen, craftspeople, white-collar workers, physicians, and lawyers.

[9] The Jewish community of Leipzig established several programs to help the needy, and by the start of World War I there were 48 active charities.

The German Reich completed a population census on May 19, 1939, in which they determined that 0.5% of Leipzig's citizens were Jewish, where 4,470 were Jews by descent and 4,113 by religion.

[15] The NSDAP regional administrative authority, along with the head revenue office and state police, were responsible for the implementation of Anti-Jewish policies.

In the fall of 1939, the NSDAP created Judenhauser, in which Jewish residents and non-Jewish spouses of "mixed-marriages" were forced to live in close quarters.

[19] The department worked closely with Palastina-Ami to ensure safe arrival to Erez Israel, and with Hilfsverein der Juden in Deutschland for emigration to all other countries.

Because many of Leipzig's Jews worked in business and the fur trade which was not needed in the country they wished to emigrate to, many of them enrolled in re-training courses where they learned blue-collar jobs such as bricklaying or carpentry.

[24] As the group of Jews headed toward the Polish border, SS men whipped them, and those who fell faced severe beatings.

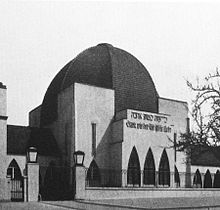

[26] The Brody Synagogue and the mourning hall of the Jewish cemetery, built according to a design by Wilhelm Haller, were also damaged heavily on this night.

Meanwhile, Jewish men and women were deported from various German-occupied countries to subcamps of the Buchenwald concentration camp, operated in the city.

[31] They were subjected to slave labour there, and sick and pregnant women and those considered unable to work were deported to other concentration camps.

[31][32] Following the deportation of Leipzig's Jews, the Germany's Revenue office visited the abandoned homes to confiscate any furniture, jewelry, and clothing that was left behind.

[38] Following this confrontation, only a few employees received a termination of their contracts, but internal pressure was starting to bubble up beneath the board of members.

[40] The Nazis urged the public to boycott Jewish furs, which made it difficult for many Jews in Leipzig to make a living.

Vulnerable on purely economic grounds, the Leipzig fur trade collapsed slightly before the Nazi crisis and during the world depression.

In Leipzig, most of the trading took place in medium-sized specialty shops where its owners were regularly held responsible for macroeconomic forces such as drastic increases in inflation.

Although these businesses were not subjects of the later systemic "aryanization" used by the Nazis in which legislation was the driving force, and, instead, were harassed, in the early stages, by party functionaries and competitors, they were often still sold or even destroyed by these factors.

[42] Henri, a successful businessman and philanthropist soon became a target of discrimination and exclusion carried out by the Berufs- und Standesorganisationen der Musikverleger (Music Publisher's Association).

[42] The process was executed by SS regiment leader Gerhard Noatzke and in July 1939, a sales contract was finalized and the property, along with its buildings such as the Peters Music Library, were sold for one million Reichsmarks.

By the end of the next year, 1939, the German economy had essentially been successfully "cleansed" of Jewish influence and movements now shifted towards residential areas.

[43] Confiscation of belongings and assets soon followed, and on January 21, 1942, deportations began in Leipzig to relocate Jews to newly marked Jewish homes.

[46] The decrease in Leipzig's Jewish community from 1935 to 1939 may be attributed to Nazi persecution and emigration, however, the population is still significant in size at this time.

The Tora Zentrum organizes weekly classes, Shabbat meals, and social events and activities for Jewish students between ages 18 and 32.