History of the Palace of Westminster

[3] Edward the Confessor, the penultimate Anglo-Saxon king, began the building of Westminster Abbey and a neighbouring palace to oversee its construction.

In 1512, during the early years of the reign of King Henry VIII, fire destroyed the royal residential ("privy") area of the palace.

[15] In 1534, Henry VIII acquired York Place from Cardinal Thomas Wolsey,[16] a powerful minister who had lost the King's favour.

Important state ceremonies were held in the Painted Chamber which had been originally built in the 13th century as the main bedchamber for King Henry III.

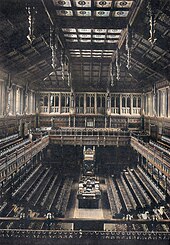

Alterations were made to St Stephen's Chapel over the following three centuries for the convenience of the lower House, gradually destroying, or covering up, its original mediaeval appearance.

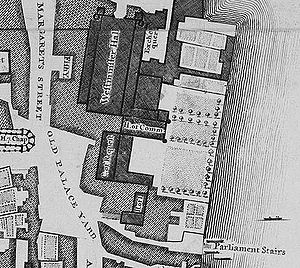

The Palace of Westminster as a whole began to see significant alterations from the 18th century onwards, as Parliament struggled to carry out its business in the limited available space and ageing buildings.

A new west façade, known as the Stone Building, facing onto St Margaret's Street was designed by John Vardy built in the Palladian style between 1755 and 1770, providing more space for document storage and committee rooms.

The House of Commons Engrossing Office of Henry (Robert) Gunnell (1724–1794) and Edward Barwell was on the lower floor beside the corner tower at the west side of Vardy's western façade.

The neo-Gothic architect James Wyatt also carried out works on both the House of Lords and Commons between 1799 and 1801, including alterations to the exterior of St Stephen's Chapel and a much-derided new neo-Gothic building, referred to by Wyatt's critics as "The Cotton Mill" adjoining the House of Lords and facing onto Old Palace Yard.

The medieval House of Lords chamber, which had been the target of the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, was demolished as part of this work in order to create a new Royal Gallery and ceremonial entrance at the southern end of the palace.

Soane's work at the palace also included new library facilities for both Houses of Parliament and new law courts for the Chancery and King's Bench.

[18] Immediately after the fire, King William IV offered the almost-completed Buckingham Palace to Parliament, hoping to dispose of a residence he disliked.

[19] Proposals to move to Charing Cross or St James's Park had a similar fate; the allure of tradition and the historical and political associations of Westminster proved too strong for relocation, despite the deficiencies of that site.

[27] Decimus Burton and his pupils commended the purchase of the Elgin Marbles for the nation, and the erection of a neoclassical gallery in which they could be displayed to the same, and subsequently contended that the destruction of the Houses of Parliament by the fire of 1834 was an opportunity for the creation of a splendid neoclassical replacement of the Houses of Parliament, in which the Elgin Marbles could be displayed: they expressed their aversion that the new seat of the British Empire would ‘be doomed to crouch and wither in the groinings [sic], vaultings, tracery, pointed roof, and flying buttresses of a Gothic building…’:[28] a building of a style that they contended to be improper ‘to the prevailing sentiment of an age so enlightened’.

[32] The Architectural Magazine summarised Barry's winning plan as "a quadrangular pile, with the principal front facing the Thames, and a tower in the centre, 170ft high".

[38] Pugin attempted to popularize advocacy of the neo-gothic, and repudiation of the neoclassical, by composing and illustrating books that contended the supremacy of the former and the degeneracy of the latter, which were published from 1835.

[40] In a process overseen by a Royal Fine Art Commission under the presidency of Prince Albert, a Select Committee which included Sir Robert Peel started to take witness accounts from experts in 1841.

Those experts included Sir Martin Archer Shee, P.R.A., and Charles Lock Eastlake, painter and acknowledged authority on art history, soon to be first director of the National Gallery and de facto administrator of the whole Westminster decoration project.

One bomb fell into Old Palace Yard on 26 September 1940 and severely damaged the south wall of St Stephen's Porch and the west front.

[41] The statue of Richard the Lionheart was lifted from its pedestal by the force of the blast, and its upheld sword bent, an image that was used as a symbol of the strength of democracy, "which would bend but not break under attack".

[41] The worst raid took place in the night of 10–11 May 1941, when the Palace took at least twelve hits and three people (two policemen and the Resident Superintendent of the House of Lords, Edward Elliott[43]) were killed.

The work was undertaken by John Mowlem & Co.,[48][full citation needed] and construction lasted until 1950, when King George VI opened the new chamber in a ceremony which took place in Westminster Hall on 26 October.