Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Russian Civil War broke out in late 1917 after the Bolshevik Revolution and Vladimir Lenin, the first leader of the new Soviet Russia, recognised the independence of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

His response to the political checkmate would later be heard at a rally in Wilhelmshaven: "No power on earth would be able to break German might, and if the Western Allies thought Germany would stand by while they marshalled their 'satellite states' to act in their interests, then they were sorely mistaken".

[43] On 31 March 1939, in response to Germany's defiance of the Munich Agreement and the creation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia,[44] Britain pledged its support and that of France to guarantee the independence of Poland, Belgium, Romania, Greece and Turkey.

[50][51][52] The Soviet Union, which feared Western powers and the possibility of "capitalist encirclements", had little hope of preventing war and wanted nothing less than an ironclad military alliance with France and Britain[53] to provide guaranteed support for a two-pronged attack on Germany.

[58] The contrasting attitudes partly explain why the Soviets have often been charged with playing a double game in 1939 of carrying on open negotiations for an alliance with Britain and France but secretly considering propositions from Germany.

[68] The ensuing discussion of a potential political deal between Germany and the Soviet Union had to be channeled into the framework of economic negotiations between the two countries, since close military and diplomatic connections that existed before the mid-1930s had been largely severed.

[69] In May, Stalin replaced his foreign minister from 1930 to 1939, Maxim Litvinov, who had advocated rapprochement with the West and was also Jewish,[70] with Vyacheslav Molotov to allow the Soviet Union more latitude in discussions with more parties, instead of only Britain and France.

After stepping off the plane and shaking hands, Ribbentrop and Gustav Hilger along with German ambassador Friedrich-Werner von der Schulenburg and Stalin's chief bodyguard, Nikolai Vlasik, entered a limousine operated by the NKVD to travel to Red Square.

[80][81][82][83] At the same time, British, French, and Soviet negotiators scheduled three-party talks on military matters to occur in Moscow in August 1939 that aimed to define what the agreement would specify on the reaction of the three powers to a German attack.

[50][89] The same day, Stalin received assurances that Germany would approve secret protocols to the proposed non-aggression pact that would place the half of Poland east of the Vistula River as well as Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Bessarabia in the Soviet sphere of influence.

[97] The same day, the New York Times also reported from Montreal, Canada, that American Professor Samuel N. Harper of the University of Chicago had stated publicly his belief that "the Russo-German non-aggression pact conceals an agreement whereby Russia and Germany may have planned spheres of influence for Eastern Europe".

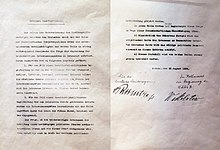

[99] On 23 August, a ten-year non-aggression pact was signed with provisions that included consultation, arbitration if either party disagreed, neutrality if either went to war against a third power and no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other".

The article "On Soviet–German Relations" in the Soviet newspaper Izvestia of 21 August 1939, stated: Following completion of the Soviet–German trade and credit agreement, there has arisen the question of improving political links between Germany and the USSR.

[104] They characterised Britain as always attempting to disrupt Soviet–German relations and stated that the Anti-Comintern Pact was aimed not at the Soviet Union but actually at Western democracies and "frightened principally the City of London [British financiers] and the English shopkeepers.

[106] The news was met with utter shock and surprise by government leaders and media worldwide, most of whom were aware of only the British–French–Soviet negotiations, which had taken place for months;[50][106] by Germany's allies, notably Japan; by the Comintern and foreign Communist parties; and Jewish communities all around the world.

[132]In the opinion of Robert Service, Stalin did not move instantly but was waiting to see whether the Germans would halt within the agreed area, and the Soviet Union also needed to secure the frontier in the Soviet–Japanese Border Wars.

[136] On 18 September, The New York Times published an editorial arguing that "Hitlerism is brown communism, Stalinism is red fascism...The world will now understand that the only real 'ideological' issue is one between democracy, liberty and peace on the one hand and despotism, terror and war on the other.

[145] On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and German Reich issued a joint declaration in which they declared: After the Government of the German Reich and the Government of the USSR have, by means of the treaty signed today, definitively settled the problems arising from the collapse of the Polish state and have thereby created a sure foundation for lasting peace in the region, they mutually express their conviction that it would serve the true interest of all peoples to put an end to the state of war existing at present between Germany on the one side and England and France on the other.

[146]On 3 October, Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg, the German ambassador in Moscow, informed Joachim Ribbentrop that the Soviet government was willing to cede the city of Vilnius and its environs.

[157][158][159][160] The leader of the Leningrad Military District, Andrei Zhdanov, commissioned a celebratory piece from Dmitri Shostakovich, Suite on Finnish Themes, to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army would be parading through Helsinki.

"[211] Gunther wrote, however, that some knew "communism and Fascism were more closely allied than was normally understood", and Ernst von Weizsäcker had told Nevile Henderson on 16 August that the Soviet Union would "join in sharing in the Polish spoils".

When the various departments of the Foreign Office in Berlin were evacuated to Thuringia at the end of the war, Karl von Loesch, a civil servant who had worked for the chief interpreter Paul Otto Schmidt, was entrusted with the microfilm copies.

[244] Both documents were discovered as part of the microfilmed records in August 1945 by US State Department employee Wendell B. Blancke, the head of a special unit called "Exploitation German Archives" (EGA).

Later, Seidl obtained the German-language text of the secret protocols from an anonymous Allied source and attempted to place them into evidence while he was questioning witness Ernst von Weizsäcker, a former Foreign Office State Secretary.

[214] On 23 August 1986, tens of thousands of demonstrators in 21 western cities, including New York, London, Stockholm, Toronto, Seattle, and Perth participated in Black Ribbon Day Rallies to draw attention to the secret protocols.

[260][261] Both successor states of the pact parties have declared the secret protocols to be invalid from the moment that they were signed: the Federal Republic of Germany on 1 September 1989 and the Soviet Union on 24 December 1989,[262] following an examination of the microfilmed copy of the German originals.

"[274][270][275] Given Litvinov's prior attempts to create an anti-fascist coalition, association with the doctrine of collective security with France and Britain and a pro-Western orientation[276] by the standards of the Kremlin, his dismissal indicated the existence of a Soviet option of rapprochement with Germany.

[290] On the other hand, Soviet-born Australian historical writer Alex Ryvchin characterized the pact as "a Soviet deal with the devil, which contained a secret protocol providing for the remaining independent states of East-Central Europe to be treated as courses on some debauched degustation menu for two of the greatest monsters in history.

[293] A number of German historians have debunked the claim that Operation Barbarossa was a preemptive strike, such as Andreas Hillgruber, Rolf-Dieter Müller, and Christian Hartmann, but they also acknowledge that the Soviets were aggressive to their neighbors.

[309] In connection with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe parliamentary resolution condemned both communism and fascism for starting World War II and called for a day of remembrance for victims of both Stalinism and Nazism on 23 August.