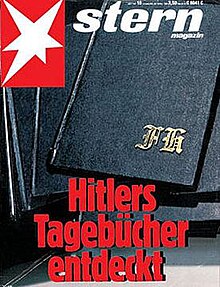

Hitler Diaries

[1][2] The final flight out was a Junkers Ju 352 transport plane, piloted by Major Friedrich Gundlfinger—on board were ten heavy chests under the supervision of Hitler's personal valet, Sergeant Wilhelm Arndt.

[4] When Baur told Hitler what had happened, the German leader expressed grief at the loss of Arndt, one of his most favoured servants, and added: "I entrusted him with extremely valuable documents which would show posterity the truth of my actions!

[7] In the decades following the war, the possibility of a hidden cache of private papers belonging to Hitler became, according to the journalist Robert Harris, a "tantalizing state of affairs [that] was to provide the perfect scenario for forgery".

[12] By 1963 the bar had begun to suffer financial difficulties, and Kujau started his career as a counterfeiter, forging 27 Deutsche Marks' (DM) worth of luncheon vouchers;[b] he was caught and sentenced to five days in prison.

He saw an opportunity to buy the material cheaply on the black market, and make a profit in the West, where the increasing demand among Stuttgart collectors was raising memorabilia prices up to ten times the amount he would pay.

He forged passable imitations of his subjects' genuine handwriting, but the rest of the work was crude: Kujau used modern stationery such as Letraset to create letterheads, and he tried to make his products look suitably old by pouring tea over them.

[24] Having found success in passing off his forged notes as those of Hitler, Kujau grew more ambitious and copied, by hand, the text from both volumes of Mein Kampf, even though the originals had been completed by typewriter.

[32] The purchase of the yacht caused Heidemann financial problems, and in 1976 he agreed terms with Gruner + Jahr, Stern's parent company, to produce a book based on the conversations he was having with the former soldiers and SS men.

[33] When the book went unwritten—the material provided by the former SS officers was not sufficiently interesting or verifiable for publication—Heidemann borrowed increasingly large sums from his employers to pay for the boat's upkeep.

In his place Stern had three editors: Peter Koch, Rolf Gillhausen and Felix Schmidt, who were aided by others including the journal's head of contemporary history, Thomas Walde.

The pair did not show the prospectus to anyone at Stern, but instead presented it to Gruner + Jahr's deputy managing director, Jan Hensmann, and Manfred Fischer; they also requested a 200,000 mark deposit from the publisher to secure the rights with Kujau.

Kujau claimed ignorance, saying he was only the middleman, but told them that Heidemann, a reputed journalist, had seen the crash site from which the papers originated; Jäckel advised Stiefel to have his collection forensically examined,[63] and passed 26 suspect poems to the Hamburg district attorney for investigation.

It contained a deal for him to publish books through the company at a generous royalty rate, and agreed that ten years after publication the original diaries would be given to Heidemann for research purposes, to be handed on to the West German government on his death.

[78] Heidemann visited Maser in June 1981 and came to a deal that enabled the journalist and Stern, for a payment of 20,000 DMs, to retain "the rights to all the discovered or purchased documents or notes in the hand of Adolf Hitler ... which have so far not yet been published".

The journalist was starting to lead a profligate lifestyle on his illicit profits, including two new cars (a BMW convertible and a Porsche, for a combined total of 58,000 DMs), renting two new flats on Hamburg's exclusive Elbchaussee and jewellery.

[86][o] In April 1982 Walde and Heidemann contacted Josef Henke and Klaus Oldenhage of the Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archives) and Max Frei-Sulzer, the former head of the forensic department of the Zürich police, for assistance in authenticating the diaries.

To ensure wide readership and to maximise their returns, Stern issued a prospectus to potentially interested parties, Newsweek, Time, Paris Match and a syndicate of papers owned by Murdoch.

[95] As the background to the acquisition was explained to him he became less doubtful; he was falsely informed that the paper had been chemically tested and been shown to be pre-war, and he was told that Stern knew the identity of the Wehrmacht officer who had rescued the documents from the plane and had stored them ever since.

"[97] In an article in The Times on 23 April 1983 he wrote: I am now satisfied that the documents are authentic; that the history of their wanderings since 1945 is true; and that the standard accounts of Hitler's writing habits, of his personality, and even, perhaps, of some public events may, in consequence, have to be revised.

[105] On hearing the news from Stern, Jäckel stated that he was "extremely sceptical" about the diaries, while his fellow historian, Karl Dietrich Bracher of the University of Bonn also thought their legitimacy unlikely.

[107] The following day The Times published the news that their Sunday sister paper had the serialisation rights for the UK; the edition also carried an extensive piece by Trevor-Roper with his opinion on the authenticity and importance of the discovery.

"[109][110] On the afternoon of the 24 April, in Hamburg for the press conference the following day, Trevor-Roper asked Heidemann for the name of his source: the journalist refused, and gave a different story of how the diaries had been acquired.

[114] Irving, who had been described in the introductory statement by Koch as a historian "with no reputation to lose", stood at the microphone for questions, and asked how Hitler could have written his diary in the days following the 20 July plot, when his arm had been damaged.

[118] While the debate on the diaries' authenticity continued, Stern published its special edition on 28 April, which provided Hitler's purported views on the flight of Hess to Scotland, Kristallnacht and the Holocaust.

[122] The same day Hagen visited the Bundesarchiv and was told of their findings: ultraviolet light had shown a fluorescent element to the paper, which should not have been present in an old document, and that the bindings of one of the diaries included polyester which had not been made before 1953.

Harris describes how a bunker mentality descended on the Stern management as, instead of accepting the truth of the Bundesarchiv's findings, they searched for alternative explanations as to how post-war whitening agents could have been used in the wartime paper.

The initial results were ready on 6 May, which confirmed what the forensic experts had been telling the management of Stern for the last week: the diaries were poor forgeries, with modern components and ink that was not in common use in wartime Germany.

[132][133][q] Despite the seriousness of the charges facing the two men, Hamilton considers that "it also appeared clear that the trial was going to be a farce, a real slapstick affair that would enrage the judge and amuse the entire world.

In September one of the supporting magistrates overseeing the case was replaced after he fell asleep;[138] three days later the court were "amused" to see pictures of Idi Amin's underpants, which Heidemann had framed on his wall.

It starred Jonathan Pryce as Heidemann, Alexei Sayle as Kujau, Tom Baker as Fischer, Alan Bennett as Trevor-Roper, Roger Lloyd-Pack as Irving, Richard Wilson as Nannen and Barry Humphries as Murdoch.