Hollywood blacklist

Although the blacklist had no official end date, it was generally recognized to have weakened by 1960, the year when Dalton Trumbo – a CPUSA member from 1943 to 1948,[3] and also one of the "Hollywood Ten" – was openly hired by director Otto Preminger to write the screenplay for Exodus (1960).

The first systematic Hollywood blacklist was instituted on November 25, 1947, the day after ten left-wing screenwriters and directors were cited for contempt of Congress for refusing to answer questions before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

The ten men—Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott and Dalton Trumbo—had been subpoenaed by the committee in late September to testify about their Communist affiliations and associates.

After Leech repeated his charges in supposed confidence to a Los Angeles grand jury, many of the names were leaked to the press, including those of stars Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Katharine Hepburn, Melvyn Douglas and Fredric March, among other Hollywood figures.

In 1945, Gerald L. K. Smith, founder of the neofascist America First Party, began giving speeches in Los Angeles assailing the "alien minded Russian Jews in Hollywood.

"[16] Mississippi congressman John E. Rankin, an HUAC member, held a press conference to declare that "one of the most dangerous plots ever instigated for the overthrow of this Government has its headquarters in Hollywood ... the greatest hotbed of subversive activities in the United States."

The growth of conservative political influence and the Republican triumph in the 1946 midterm elections, which saw the GOP take control of both the House and Senate, led to a major revival of institutional anti-communist activity, publicly spearheaded by the HUAC but with an investigative push by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI.

[24] In late September 1947, drawing upon the lists provided in The Hollywood Reporter, the House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenaed 42 persons working in the film industry to testify at hearings.

"[29] Unlike the friendly witnesses, other leading Hollywood figures—including directors John Huston, Billy Wilder, and William Wyler; and actors Lauren Bacall, Lucille Ball, Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis, Henry Fonda, John Garfield, Judy Garland, Sterling Hayden, Katharine Hepburn, Danny Kaye, Gene Kelly, Myrna Loy, and Edward G. Robinson—protested the HUAC and formed the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA).

[42] In light of the Hollywood Ten's defiance of the HUAC – in addition to refusing to answer questions, they also tried unsuccessfully to read opening statements decrying the House committee's investigation as unconstitutional – political pressure mounted on the film industry to demonstrate its "anti-subversive" bona fides.

Late in the hearings, Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), vowed to the committee that he would never "employ any proven or admitted Communist because they are just a disruptive force, and I don't want them around.

The next day, after a meeting of nearly 50 film industry executives at New York City's Waldorf-Astoria hotel, MPAA President Johnston issued a press release that is today referred to as the Waldorf Statement.

Humphrey Bogart, who had been a key member of the Committee for the First Amendment, felt compelled to write an essay, printed in the May 1948 issue of Photoplay magazine, that vigorously denied he was a Communist sympathizer.

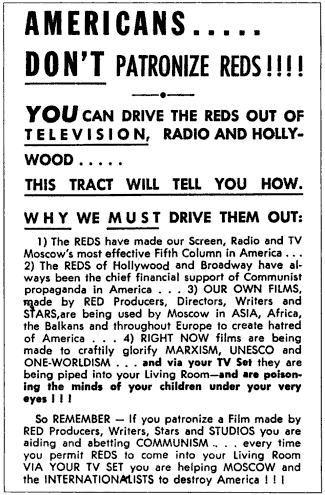

[50] A number of non-governmental organizations participated in enforcing and expanding the blacklist; in particular, the American Legion, the conservative war veterans' group, was instrumental in pressuring the studios to ban Communists and fellow travelers.

[56] Historians sometimes distinguish between (a) the "official blacklist" – i.e., the names of those who were called by the HUAC and, in whatever manner, refused to cooperate or were identified as Communists in the hearings – and (b) the graylist – those who were denied work because of their political or personal affiliations, real or imagined.

The graylist also refers more specifically to those who were denied work by the major studios but could still find jobs on Poverty Row: Composer Elmer Bernstein, for instance, was called before the HUAC when it was discovered he had written some music reviews for a Communist newspaper.

[57] While there were film artists like Parks and Dmytryk who eventually cooperated with the HUAC, other friendly witnesses gave damaging testimony with less apparent hesitation or reluctance, most notably director Elia Kazan and screenwriter Budd Schulberg.

According to historians Paul Buhle and David Wagner, "premature strokes and heart attacks were fairly common [among blacklistees], along with heavy drinking as a form of suicide on the installment plan.

"Another noted that screenwriter Lester Cole had inserted lines from a famous pro-Loyalist speech by La Pasionaria about it being 'better to die on your feet than to live on your knees' into a pep talk delivered by a football coach.

In a Reason magazine article entitled "Hollywood's Missing Movies", Kenneth Billingsley cites a case where Trumbo "bragged" in the Daily Worker about quashing films with anti-Soviet content: among them were proposed adaptations of Arthur Koestler's anti-totalitarian books Darkness at Noon and The Yogi and the Commissar, which described the rise of communism in Russia, and Victor Kravchenko's I Chose Freedom.

That's when the blacklisted Dalton Trumbo inadvertently received screen credit for having written, years earlier, the story on which the screenplay for Columbia Pictures' Emergency Wedding was based.

[70] As William O'Neill notes, pressure was maintained even on those who had ostensibly been cleared: On December 27, 1952, the American Legion announced that it disapproved of a new film, Moulin Rouge, starring José Ferrer, who used to be no more progressive than hundreds of other actors and had already been grilled by HUAC.

[73] During this same period, a number of powerful newspaper columnists covering the entertainment industry, including Walter Winchell, Hedda Hopper, Victor Riesel, Jack O'Brian, and George Sokolsky, regularly suggested names that should be added to the blacklist.

[74] Actor John Ireland received an out-of-court settlement to end a 1954 lawsuit against the Young & Rubicam advertising agency, which had ordered him dropped from the lead role in a TV series it sponsored.

Variety described it as "the first industry admission of what has for some time been an open secret – that the threat of being labeled a political non-conformist, or worse, has been used against show business personalities, and that a screening system is at work determining these [actors'] availabilities for roles.

Fund-raising for once-popular humanitarian efforts became difficult, and despite the sympathies of many in the industry there was little open support in Hollywood for causes such as the Civil Rights Movement and the opposition to nuclear weapons testing.

For this project, he and the newly formed Independent Productions Corporation worked in New Mexico, outside the studio system, with a group of blacklisted professionals: producer Paul Jarrico, writer Michael Wilson, and actor Will Geer.

[88] On November 30, 1958, a live CBS production of Wonderful Town, based on short stories written by then-Communist Ruth McKenney, appeared with the proper writing credit of blacklisted Edward Chodorov, along with his literary partner, Joseph Fields.

[91] Six and a half months later, with Exodus still to debut, The New York Times reported that Universal Pictures would give Trumbo screen credit for his writing work on Spartacus, a decision now recognized as being largely made by the film's star/producer Kirk Douglas.

Others, like actor Lee J. Cobb and director Michael Gordon, who gave friendly testimony to HUAC after suffering on the blacklist for a time, "concede[d] with remorse that their plan was to name their way back to work.