Homelessness in Greece

[3] Favouritism of the free market became more prevalent in Southern Europe in the late 1980s as well as 1990s, manifesting as cuts to social welfare and deregulation of urban development.

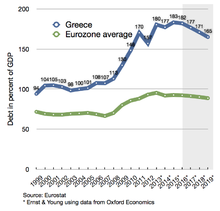

[5] The conditions of structural reform and austerity measures meant that income, pensions, unemployment, savings, and other economic factors were all impacted.

Expenditure on the National Health System and reductions in pensions and welfare benefits also took place, eroding the level of disposable income for many Greeks.

[5] The non-profit organisation Klimaka introduced the term "neo-homelessness" as a descriptor[3] of the diverse population of people rendered homeless by the fiscal crisis in Greece.

Homeless people who have experienced unemployment and low income, a lack of supportive networks, and mental health issues (often coupled with gambling, drug, or alcohol abuse) are placed in this category.

[2] The National Company of Electricity released a statement in 2016 estimating that 350,000 clients had debts valued at a total of approximately 1 billion euros.

[2] Refugees crossing the Greek-Macedonian borders after the 2016 EU-Turkey deal were displaced[8] and sought accommodation in camps, athletic fields, airports, and ports.

[3] During the transpiration of the economic crisis, an increase in calls relating to domestic violence and welfare issues as well as unexpected crises were made to the National Centre for Social Solidarity.

[5] Demand for unaffordable urban space has led to informal construction and unplanned residential development in areas traditionally intended for agricultural and forest land use.

[11] Homelessness and the inability to pay for formal dwellings in major cities such as Athens has contributed to this urban sprawling process which incurs threats to biodiversity, desertification, and local water contamination.

[12] The Housing and Reintegration Program was created in the pressurised fiscal environment in 2013, with €9.25 million allocated to local municipalities, NGOs, regional authorities, and church foundations.

[12] Since then, a National Strategy for Homelessness was established in 2018 with the aims of recording annual reduction targets, updating relevant legislation, and creating a separate sub-mechanism for stakeholder collaboration.

[2] At a local level, authorities have started to become operational centres for a variety of social services including public space regulation, recognition of beneficiaries for housing assistance, and support for financially vulnerable people.

[2] Municipalities have cooperated with non-profit organisations to create ‘Day Centres’ and ‘Night Shelters’, as well as integrate homeless services into their plans.

[2] Other practices that municipalities provide include issuing health cards for those who are uninsured, granting allowances, and investigating the living conditions of children with juvenile court orders.

The charity Emfasis facilitates around 110 volunteers in Athens who give advice on welfare access and distribute food, blankets, books, and other essential goods.

[13] Another NGO called Praksis runs a day centre which allows people to wash their clothes, take a shower, and sleep in a bed.