Homestead strike

It now became possible to make steel suitable for structural beams and for armor plate for the United States Navy, which paid far higher prices for the premium product.

Carnegie installed vastly improved systems of material-handling, like overhead cranes, hoists, charging machines, and buggies.

Although victorious, the union agreed to significant wage cuts that left tonnage rates less than half those at the nearby Jones and Laughlin works, where technological improvements had not yet been made.

The union contract contained 58 pages of footnotes defining work rules at the plant and strictly limited management's ability to maximize output.

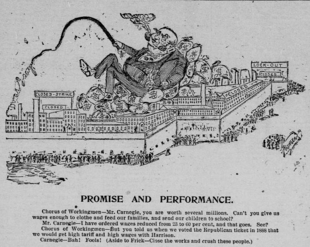

[14] But Carnegie agreed with Frick's desire to break the union and "reorganize the whole affair, and ... exact good reasons for employing every man.

[16] With the collective bargaining agreement due to expire on June 30, 1892, Frick and the leaders of the local AA union entered into negotiations in February.

Frick immediately countered with a 22% wage decrease that would affect nearly half the union's membership and remove a number of positions from the bargaining unit.

Then Frick offered a slightly better wage scale and advised the superintendent to tell the workers, "We do not care whether a man belongs to a union or not, nor do we wish to interfere.

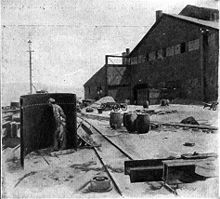

Sniper towers with searchlights were constructed near each mill building, and high-pressure water cannons (some capable of spraying boiling-hot liquid) were placed at each entrance.

Carnegie corporation attorney Philander Knox gave the go-ahead to the sheriff on July 5, and McCleary dispatched 11 deputies to the town to post handbills ordering the strikers to stop interfering with the plant's operation.

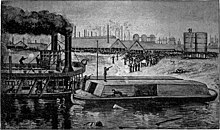

Three hundred Pinkerton agents assembled on the Davis Island Dam on the Ohio River about five miles below Pittsburgh at 10:30 p.m. on the night of July 5, 1892.

[29] The Pinkertons attempted to land under cover of darkness about 4 a.m. A large crowd of families had kept pace with the boats as they were towed by a tug into the town.

[34] The strikers then huddled behind the pig and scrap iron in the mill yard, while the Pinkertons cut holes in the side of the barges so they could fire on any who approached.

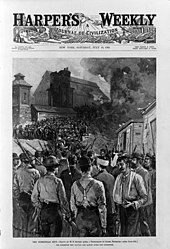

The burgess of Homestead, John McLuckie, issued a proclamation at 6:00 a.m. asking for townspeople to help defend the peace; more than 5,000 people congregated on the hills overlooking the steelworks.

Six miles away in Pittsburgh, thousands of steelworkers gathered in the streets, listening to accounts of the attacks at Homestead; hundreds, many of them armed, began to move toward the town to assist the strikers.

At 9:00 a.m., outgoing AA international president William Weihe rushed to the sheriff's office and asked McCleary to convey a request to Frick to meet.

In a telegram to Governor Pattison, he described how his deputies and the Carnegie men had been driven off, and noted that the workers and their supporters actively resisting the landing numbered nearly 5,000.

Weihe tried to speak again, but this time his pleas were drowned out as the strikers bombarded the barges with fireworks left over from the recent Independence Day celebration.

The press expressed shock at the treatment of the Pinkerton agents, and the torrent of abuse helped turn media sympathies away from the strikers.

[48] But when the Pinkerton agents arrived at their final destination in Pittsburgh, state officials declared that they would not be charged with murder (per the agreement with the strikers) but rather simply released.

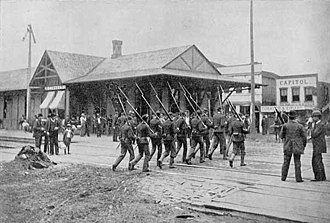

[63] On July 7, the strike committee sent a telegram to Governor Pattison to attempt to persuade him that law and order had been restored in the town.

Pattison's refusal to act rested largely on his concern that the union controlled the entire city of Homestead and commanded the allegiance of its citizens.

Despite the presence of AFL pickets in front of several recruitment offices across the nation, Frick easily found employees to work the mill.

The company quickly built bunk houses, dining halls and kitchens on the mill grounds to accommodate the strikebreakers.

[69] Desperate to find a way to continue the strike, the AA appealed to Whitelaw Reid, the Republican candidate for vice president, on July 16.

[71] National attention became riveted on Homestead when, on July 23, Alexander Berkman, a New York anarchist with no connection to steel or to organized labor, plotted with his lover Emma Goldman to assassinate Frick.

Hugh O'Donnell was removed as chair of the strike committee when he proposed to return to work at the lower wage scale if the unionists could get their jobs back.

Hugh Dempsey, the leader of the local Knights of Labor District Assembly, was found guilty of conspiring to poison[76] nonunion workers at the plant—despite the state's star witness recanting his testimony on the stand.

[citation needed] De-unionization efforts throughout the Midwest began against the AA in 1897 when Jones and Laughlin Steel refused to sign a contract.

[citation needed] In 1999 the Bost Building in downtown Homestead, AA headquarters throughout the strike, was designated a National Historic Landmark.