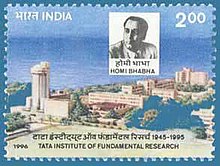

Homi J. Bhabha

He often visited his paternal aunt Meherbai Tata, who owned a Western classical music collection which included the works of Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn and Schubert.

There, he was privy to conversations Dorabji had with national leaders of the independence movement, like Mahatma Gandhi and Motilal Nehru, as well as business dealings in industries like steel, heavy chemicals and hydroelectric power which the Tata Group invested in.

This was due to the insistence of his father and his uncle Dorabji, who planned for Bhabha to obtain a degree in mechanical engineering from Cambridge and then return to India, where he would join the Tata Steel mills in Jamshedpur as a metallurgist.

He also designed the sets for a student performance of Pedro Calderón de la Barca's play Life is a Dream and Mozart's Idomeneo for the Cambridge Musical Society.

During his studentship, Bhabha also visited Hans Kramers, who was then a professor conducting theoretical research in the interaction of electromagnetic waves with matter at Utrecht University.

In 1933, Bhabha was selected for the Isaac Newton scholarship, which he held for the next three years and used to fund his time working with Enrico Fermi at the Institute of Physics in Rome.

Bhabha later concluded that observations of the properties of the meson would lead to the straightforward experimental verification of the time dilation phenomenon predicted by Albert Einstein's theory of relativity.

War prompted him to remain in India, where he accepted a post of reader in physics at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru headed by Nobel laureate C.V.

[35][36] As late as 1940, Bhabha was listing his affiliation as "at present at the Department of Physics, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore", suggesting that he viewed his time in India as a temporary period before his return to the UK.

[38] In a 1944 letter, he expressed a change of mind and a desire to stay in India:I had the idea that after the war I would accept a job in a good university in Europe or America.

[39]In a letter to the astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Bhabha described that his ambition was to "bring together as many outstanding scientists as possible … so as to build up in time an intellectual atmosphere approaching what we knew in places like Cambridge and Paris.

"[34] The scholar George Perkovich argues that due to this secrecy and the AEC's relative freedom from government control, the "Nehru-Bhabha relationship constituted the only potentially real mechanism to check and balance the nuclear programme".

[54] When Bhabha realised that technology development for the atomic energy programme could no longer be carried out within TIFR he proposed to the government to build a new laboratory entirely devoted to this purpose.

[57] In a 1957 paper in Nature summarizing the Indian nuclear energy programme's ambitions and work, Bhabha claimed that "[a]lthough the Atomic Energy Commission was established as an advisory body in 1948 in the Ministry of Natural Resources and Scientific Research, no important effort to develop this work was made until a separate department of the Government of India with the full powers of a ministry was established in August 1954.

Running on enriched natural uranium fuel supplied by the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Commission and thorium, APSARA represented the first stage of Bhabha's plan: it would be useful in producing plutonium.

Bhabha was able to secure favourable terms for India partly due to his friendship with Sir John Cockcroft, who had been his colleague at the Cavendish laboratory in Cambridge.

[69][70][71] That year, India and Canada signed an agreement for the construction of a natural uranium, heavy water-moderated National Research Experimental (NRX) reactor in Trombay.

[33] According to the IAEA's 10 September 1956 draft statute, plutonium and other special fissionable materials would be deposited with the agency, which would have the discretion to provide states with quantities deemed suitable for nonmilitary use under safeguards.

Bhabha successfully lobbied against the agency's broad authority, arguing in a 27 September 1956 conference that it was the "inalienable right of States to produce and hold the fissionable material required for the peaceful power programmes".

However, M. G. K. Menon, the new director of TIFR, pushed back against Cockcroft's statement, arguing that the motivation behind setting up the Indian plutonium reprocessing plant "has sometimes been misunderstood".

"[91] This repudiated Shastri's policy preferences, who, as a Gandhian, showed a strong moral revulsion to building nuclear weapons, and did not wish to increase defence spending during the nation's ongoing food crisis.

In a remark likely aimed at Bhabha's All India Radio broadcast, Shastri added that "scientists should realise that it was the responsibility of the Government to defend the country and adopt appropriate measures".

As "the majority of speakers [had come] out strongly and frankly in favour of India manufacturing atom bombs" at the meeting, the Hindustan Times called Shastri's successful opposing address "nothing short of a miracle".

This group produced artists like F. N. Souza, M. F. Husain, Tyeb Mehta, K. H. Ara and S. H. Raza, some of whose early works Bhabha selected for the TIFR collection.

He was elected a Foreign Honorary Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1958,[120] and appointed the President of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics from 1960 to 1963.

[121] Bhabha received several honorary doctoral degrees in science throughout his career: Patna (1944), Lucknow (1949), Banaras (1950), Agra (1952), Perth (1954), Allahabad (1958), Cambridge (1959), London (1960) and Padova (1961).

In a ceremony mourning his death, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi quoted:To lose Dr Homi Bhabha at this crucial moment in the development of our atomic energy programme is a terrible blow for our nation.

[124]Many possible theories have been advanced for the air crash, including a claim that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was involved in paralysing India's nuclear program.

According to Douglas, Crowley claimed that the CIA was responsible for assassinating Homi Bhabha and Prime Minister Shastri in 1966, thirteen days apart, to thwart India's nuclear programme.

[131] Douglas asserted that Crowley told him a bomb in the cargo section of the plane exploded mid-air, bringing down the commercial Boeing 707 airliner in Alps with few traces.

![[[Air India Flight 101]] crash site](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Air_India_Flight_101_VT-DMN_crashsite.jpg/220px-Air_India_Flight_101_VT-DMN_crashsite.jpg)