Homiletics

In religious studies, homiletics (Ancient Greek: ὁμιλητικός[1] homilētikós, from homilos, "assembled crowd, throng"[2]) is the application of the general principles of rhetoric to the specific art of public preaching.

The sermons to the faithful in the early ages were of the simplest kind, being merely expositions or paraphrases of the passage of scripture that was read, coupled with extempore effusions of the heart.

A regular structure arose: the speaker first quoted a verse from the Bible, then expounded on it, and finally closed with a summary and a prayer of praise.

A custom springing from this had spread to the north of Africa; but Valerius, Bishop of Hippo, broke through it, and had St. Augustine, as yet a priest, to preach before him, because he himself was unable to do so with facility in the Latin language – "cum non satis expedite Latino sermone concionari posset".

This was against the custom of the place, as Possidius relates; but Valerius justified his action by an appeal to the East – "in orientalibus ecclesiis id ex more fieri sciens".

Even during the time of the prohibition in Alexandria, priests from Socrates and Sozomen, interpreted the Scriptures publicly in Cæsarea, in Cappadocia, and in Cyprus, candles being lighted the while – accensis lucernis.

Then for the first time, if, perhaps, we except St. Cyprian, the art of oratory was applied to preaching, especially by St. Gregory of Nazianzus, the most florid of Cappadocia's triumvirate of genius.

He was already a trained orator, as were many of his hearers, and it is no wonder, as Otto Bardenhewer[13] expresses it, "he had to pay tribute to the taste of his own time which demanded a florid and grandiloquent style".

Quite the contrary; St. Chrysostom's homilies were models of simplicity, and he frequently interrupted his discourse to put questions in order to make sure that he was understood; while St. Augustine's motto was that he humbled himself that Christ might be exalted.

An edict was issued by King Guntram stating that the assistance of the public judges was to be used to bring to the hearing of the word of God, through fear of punishment, those who were not disposed to come through piety.

As to style, it was simple and majestic, possessing little, perhaps, of so-called eloquence as at present understood, but much religious power, with an artless simplicity, a sweetness and persuasiveness all its own, and such as would compare favourably with the hollow declamation of a much-lauded later period.

And, even in this appeal, philosophy, while, like algebra, speaking the formal language of intellect, is likely to be wanting from the view-point of persuasiveness, inasmuch as, from its nature, it makes for condensation rather than for amplification.

[4] In the eighteenth century, the Austrian Jesuit Ignaz Wurz was often considered the standard author; he taught at the University of Vienna and his Anleitung zur geistlichen Beredsamkeit (Ministers' manual for eloquence) was published in several editions beginning in 1770.

The power of Lacordaire as an orator was beyond question; but the conférences, as they have come down to us, while possessing much merit, are an additional proof that oratory is too elusive to be committed to the pages of a book.

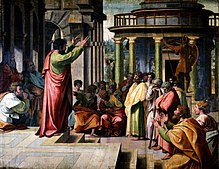

It was used by Christ Himself, by St. Paul, by Cyril of Jerusalem, by Clement and Origen at Alexandria, by Augustine, who wrote a special treatise thereon (De catechizandis rudibus), also, in later times, by Gerson, chancellor of the University of Paris, who wrote "De parvulis ad Christum trahendis"; Clement XI and Benedict XIV gave to it all the weight of their authority, and one of the greatest of all catechists was Charles Borromeo.

There is the danger, however, from the very nature of the subject, of this form of preaching becoming too dry and purely didactic, a mere catechesis, or doctrinism, to the exclusion of the moral element and of Sacred Scripture.

In the United States, particularly, this form of religious activity has flourished; and the Paulists, amongst whom the name of Isaac Hecker is deserving of special mention, are to be mainly identified with the revival.

Special facilities are afforded at the central institute of the organization for the training of those who are to impart catechetical instruction, and the non-controversial principles of the association are calculated to commend it to all earnestly seeking after religion.

[4] In the Roman Catholic Church, the Holy See, through the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (headed as of February 2015 by Robert Sarah), has published an official guide and directory for use by bishops, priests, and deacons, who are charged with the ministry of preaching by virtue of their ordination, and for those studying the subject, among others seminarians and those in diaconal formation, called the Homiletic Directory.

[22] The Directory was developed in response to a request made by participants in the Synod of Bishops held in 2008 on the Word of God, and in accordance with the instructions of Pope Benedict XVI.

He describes it practically in relation to the classical theory of oratory, which has five parts: inventio (the choice of the subject and decision of the order), dispositio (the structure of the oration), elocutio (the arrangement of words and figure of speech), memoria (learning by heart), and pronuntiatio (the delivery).

[23] Hugh of St. Victor (died 1141) in the Middle Ages laid down three conditions for a sermon: that it should be "holy, prudent and noble", for which, respectively, he required sanctity, knowledge and eloquence in the preacher.

[4] In the ninth century Rabanus Maurus (died 856), Archbishop of Mainz, wrote a treatise De institutione clericorum, in which he depends much on Augustine.

[4] In the twelfth century Guibert, Abbot of Nogent (died 1124), wrote a famous work on preaching entitled "Quo ordine sermo fieri debet".

Humbert of Romans, General superior of the Dominicans, in the second book of his work, "De eruditione prædicatorum", claims that he can teach "a way of promptly producing a sermon for any set of men, and for all variety of circumstances".

He insists very strongly [25] on the importance of preaching, and says that it belongs principally to bishops, and baptizing to priests, the latter of whom he regards as holding the place of the seventy disciples.

His first book gives for material of preaching the usual order credenda, facienda, fugienda, timenda, appetenda and ends by saying: "Congrua materia prædicationis est Sacra Scriptura."

At his request Valerio, Bishop of Verona, wrote a systematic treatise on homiletics entitled "Rhetorica Ecclesiastica" (1575), in which he points out the difference between profane and sacred eloquence and emphasizes the two principal objects of the preacher, to teach and to move (docere et commovere).

In the nineteenth century homiletics took its place as a branch of pastoral theology, and many manuals have been written thereon, for instance in German compendia by Brand, Laberenz, Zarbl, Fluck and Schüch; in Italian by Gotti and Guglielmo Audisio; and many in French and English.

The upholders of this view point to passages in Scripture and in the Fathers, notably to the words of Paul;[29] and to the testimony of Cyprian,[30] Arnobius,[31] Lactantius,[32] and to Gregory of Nazianzus, Augustine of Hippo, Jerome and John Chrysostom.