Peking Man

Peking Man lived in a cool, predominantly steppe, partially forested environment, alongside deer, rhinos, elephants, bison, buffalo, bears, wolves, big cats, and other animals.

In 1918, while in Beijing (then referred to in the West as Peking), he was pointed towards a potentially interesting fossil deposit in the mining town of Zhoukoudian in the Fangshan District, about 50 kilometres (31 miles) southwest, by the American chemistry teacher John McGregor Gibb.

[4] As part of his world tour, the then-crown prince of Sweden (and the chairman of the Swedish China Research Committee, Andersson's benefactor) Gustaf VI Adolf visited Beijing on 22 October 1926.

At a meeting planned for the prince, Andersson presented lantern slides of Zdansky's fossil teeth, and was able to convince his friend, the Canadian palaeanthropologist Davidson Black (who worked for the Peking Union Medical College, which was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation), the Chinese geologist Weng Wenhao (the head of the China Geological Survey), and the prominent French palaeoanthropologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin to jointly take over study of Zhoukoudian.

[7] On 16 October, Bohlin extracted another fossil human tooth (specimen K11337),[8] which Black made the holotype of a new genus and species called Sinanthropus pekinensis a few weeks later, accrediting the authority to both himself and Zdansky.

[9] According to the biological anthropologist Noel T. Boaz and the paleoanthropologist Russell Ciochon, his decision to so quickly name a new genus may have been politically motivated—to secure further funding of the site, which had produced no anthropologically relevant finds for nearly a year—especially since Teilhard questioned whether Peking Man was actually a human or some carnivore.

[12] In 1929, Black persuaded the Peking Union Medical College, the Geological Survey of China, and the Rockefeller Foundation to found and fund the Cenozoic Research Laboratory and ensure further study of Zhoukoudian.

According to Mr. Wang Qingpu, who had written a report for the Chinese government on the history of the port, if Bowen's story is accurate, the most probable location of the fossils is 39°55′4″N 119°34′0″E / 39.91778°N 119.56667°E / 39.91778; 119.56667, underneath roads, a warehouse, or a parking lot.

[40] The productivity of Zhoukoudian elicited strong palaeoanthropological interest in China, and 14 other H. erectus sites have since been discovered across the country as of 2016 in the Yuanmou, Tiandong, Jianshi, Yunxian, Lantian, Luonan, Yiyuan, Nanzhao, Nanjing, Hexian, and Dongzhi counties.

Among them was Ernst Haeckel, who argued that the first human species (which he proactively named "Homo primigenius") evolved on the now-disproven hypothetical continent "Lemuria" in what is now Southeast Asia, from a genus he termed "Pithecanthropus" ("ape-man").

[13] In regard to the ancestry of Far Eastern peoples, the French orientalist Albert Terrien de Lacouperie advanced the now discredited theory of Sino-Babylonianism, which placed the origin of Chinese civilisation in the Near East, namely Babylon.

These ideologies not only aimed to remove imperialist influences, but also to replace ancient Chinese traditions and superstitions with western science to modernise the country, and lift its standing on the world stage to that of Europe.

In the West, this was aided by a popularising hypothesis for the origin of humanity in Central Asia,[16] championed primarily by the American palaeontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn and his apprentice William Diller Matthew.

This required them to reject Sir Raymond Dart's far more ancient South African Taung child (Australopithecus africanus) as a human ancestor when he described it in 1925, favouring Charles Dawson's 1912 hoax "Piltdown Man" from Britain.

Peking Man's importance in human evolution was championed by Grabau in the 1930s, who (much like Osborn) contended that the lifting of the Himalayas caused the emergence of proto-humans ("Protanthropus") in the Miocene, who then dispersed during the Pliocene into the Tarim Basin in Northwest China where they learned to control fire and make stone tools, and then went out to colonise the rest of the Old World where they evolved into "Pithecanthropus" in Southeast Asia, "Sinanthropus" in China, "Eoanthropus" (Piltdown Man) in Europe, and Homo (Kanam Mandible)[j] in Africa.

[13] Peking Man became an important matter of national pride, and was used to extend the antiquity of the Chinese people and the occupation of the region to 500,000 years ago, with discussions of human evolution becoming progressively Sinocentric even in Europe.

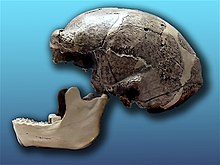

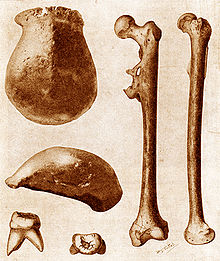

[93] Because the archaeological record of East Asia is comparatively poor, the post-cranial anatomy of H. erectus is largely based on the adolescent African specimen Turkana Boy, as well as a few other isolated skeletons from Africa and Western Eurasia.

It is debated if Peking Man occupied the region during colder glacial periods or only took residence during warmer interglacials, tied to the uncertain chronology of Zhoukoudian, as well as arguments regarding fire usage, clothing technology, and hunting ability.

In 1986, the American archaeologist Lewis Binford and colleagues reported a few horse fossils with cutmarks left by stone tools, and two upper premolars from Layer 4 appearing to him to have been burned while still fresh, which he ascribed to horse-head roasting.

[110] From Marine Isotope Stages 12–10, (roughly 500 to 340 thousand years ago), the Chinese archaeological record becomes dominated by "late-archaic" non-erectus fossils, potentially representing multiple species including the Denisovans,[111] H. longi, and H.

[41] Because human remains (encompassing males, females, and children), tools, and potential evidence of fire were found in so many layers, it has often been assumed Peking Man lived in the cave for hundreds of thousands of years.

The majority of the remains bear evidence of scars or injuries which he ascribed to attacks from clubs or stone tools; all the skulls have broken-in bases which he believed was done to extract the brain; and the femora have lengthwise splits, which he supposed was done to harvest the bone marrow.

They further proposed that deer remains, earlier assumed to have been Peking Man's prey, were instead predominantly carried in by the giant hyena Pachycrocuta, and that ash was deposited by naturally occurring wildfires fueled by bat guano, as they did not believe any human species had yet mastered hunting or fire at this time.

[33] In 2016, Shuangquan Zhang and colleagues were unable to detect significant evidence of animal, human, or water damage to the few deer bones collected from Layer 3, and concluded they simply fell into the cave from above.

In the Mao era, Peking Man was consequently often painted as leading a dangerous life in the struggle against nature, organised into simple, peaceful tribes which foraged, hunted, and made stone tools in cooperative groups.

In order to gather the fruits of the forest, to catch fish, to build some sort of habitation, men were obliged to work in common if they did not want to die of starvation, or fall victim to beasts of prey or to neighbouring societies.

[134] The crudely fractured pieces of stone from Choukoutien would never, in the vast majority of instances, have been recognized as showing traces of artificial work had they been recovered isolated in a geological deposit.The tool assemblage is otherwise characterised by mainly large, dull choppers and simple, sharp flakes.

[134] Brueil also postulated that Peking Man predominantly relied on bone tools made of prey animals' antlers, jaws, and isolated teeth, but this idea did not receive wide support.

[133] In 1929, Pei oversaw the excavation of Quartz Horizon 2 (Layer 7, Locus G) of Zhoukoudian, and reported burned bones and stones, ash, and redbud charcoal, which was interpreted as evidence of early fire usage by Peking Man.

[142] In 2001, Goldberg, Weiner, and colleagues concluded the ash layers are reworked loessic silts, and that blackened carbon-rich sediments that have been traditionally interpreted as charcoal are instead deposits of organic matter left to decompose in standing water.