Homo ergaster

There are later African fossils, some younger than 1 million years ago, that indicate long-term anatomical continuity, though it is unclear if they can be formally regarded as H. ergaster specimens.

[6] In early palaeoanthropology and well into the twentieth century, it was generally assumed that Homo sapiens was the end result of gradual modifications within a single lineage of hominin evolution.

[8] In 1975, palaeoanthropologists Colin Groves and Vratislav Mazák designated KNM ER 992 as the holotype specimen of a distinct species, which they dubbed Homo ergaster.

[12] A nearly complete fossil, interpreted as a young male (though the sex is actually undetermined), was discovered at the western shore of Lake Turkana in 1984 by Kenyan archaeologist Kamoya Kimeu.

[13] Turkana Boy was the first discovered comprehensively preserved specimen of H. ergaster/erectus found and constitutes an important fossil in establishing the differences and similarities between early Homo and modern humans.

[24] The most "iconic" fossil of H. ergaster is the KNM ER 3733 skull, which is sharply distinguished from Asian H. erectus by a number of characteristics, including that the brow ridges project forward as well as upward and arc separately over each orbit and the braincase being quite tall compared to its width, with its side walls curving.

In addition to this, the facial structure of Turkana Boy is narrower and longer than that of the other skulls, with a higher nasal aperture and likely a flatter profile of the upper face.

[26] Furthermore, KNM ER 3733 is presumed to have been the skull of a female (whereas Turkana Boy is traditionally interpreted as male), which means that sexual dimorphism may account for some of the differences.

specimen overall, showing clear similarities to KNM ER 3733, and demonstrates that early H. ergaster coexisted with other hominins such as Paranthropus robustus and Australopithecus sediba.

[10] Because H. ergaster is thought to have been ancestral to these later Homo, it might have persisted in Africa until around 600,000 years ago, when brain size increased rapidly and H. heidelbergensis emerged.

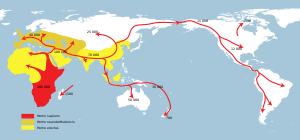

[20] Discoveries in Georgia and China push the latest possible date further back, before 2 million years ago, also casting doubt on the idea that H. ergaster was the first hominin to leave Africa.

[34] The main reason for leaving Africa is likely to have been an increasing population periodically outgrowing their resource base, with splintering groups moving to establishing themselves in neighboring, empty territories over time.

The mixture of skulls at Dmanisi suggests that the definition of H. ergaster (or H. erectus) might most appropriately be expanded to contain fossils that would otherwise be assigned to H. habilis or that two separate species of archaic humans left Africa early on.

[34] An alternative hypothesis historically has been that Homo evolved in Asia from earlier ancestors that had migrated there from Africa, and then expanded back into Europe, where it gave rise to H. sapiens.

[36] Various fossil discoveries have been used to support it through the years, including a massive set of jaws from Indonesia which were perceived to be similar to those of australopithecines and dubbed Meganthropus (now believed to be an unrelated hominid ape).

erectus first evolved in Asia before expanding back into Africa was substantially weakened by the dating of the DNH 134 skull as approximately 2 million years old, predating all other known H. ergaster/H.

[42] It is doubtful if australopithecines and earlier Homo were sufficiently mobile to make hair loss an advantageous trait, whereas H. ergaster was clearly adapted for long-distance travel and noted for inhabiting lower altitudes (and open, hot savannah environments) than their ancestors.

Genetic analysis suggests that high activity in the melanocortin 1 receptor, which produces dark skin, dates back to about 1.2 million years ago.

Though this would have been possible, it is considered unlikely, especially since the jaws and teeth of H. ergaster are reduced in size compared to those of the australopithecines, suggesting a shift in diet away from fibrous and difficult-to-chew foods.

Modern African hunter-gatherers who rely heavily on meat, such as the Hadza and San peoples, also use cultural means to recover the maximum amount of fat from the carcasses of their prey, a method that would not have been available to H.

[58] H. ergaster would thus likely have consumed large quantities of meat, vastly more than their ancestors, but would also have had to make use of a variety of other food sources, such as seeds, honey, nuts, invertebrates,[58] nutritious tubers, bulbs and other underground plant storage organs.

[40] The relatively small chewing capacity of H. ergaster, in comparison to its larger-jawed ancestors, means that the meat and high quality plant food consumed would likely have required the use of tools to process before eating.

Defense against predators would likely have come through H. ergaster living in large groups, possessing stone (and presumably wooden) tools and effective counter-attack behaviour having been established.

Cooperative behaviours such as opportunistic hunting in groups, predator defense and confrontational scavenging would have been critical for survival which means that a fundamental transition in psychology gradually transpired.

With the typical "competitive cooperation" behaviour exhibited by most primates no longer being favored through natural selection and social tendencies taking its place, hunting, and other activities, would have become true collaborative efforts.

[64] Early H. ergaster inherited the Oldowan culture of tools from australopithecines and earlier Homo, though quickly learnt to strike much larger stone flakes than their predecessors and contemporaries.

[71][72] Two of the earliest sites commonly claimed to preserve evidence of fire usage are FxJj20 at Koobi Fora and GnJi 1/6E near Lake Baringo, both in Kenya and both dated as up to 1.5 million years old.

[74] The spinal cord of Turkana Boy would have been narrower than that of modern humans, which means that the nervous system of H. ergaster, and their respiratory muscles, may not have been developed enough to produce or control speech.

[39] In 2001, anthropologists Bruce Latimer and James Ohman concluded that Turkana Boy was afflicted by skeletal dysplasia and scoliosis, and thus would not have been representative of the rest of his species in this respect.

[76] In 2013 and 2014, anthropologist Regula Schiess and colleagues concluded that there was no evidence of any congenital defects in Turkana Boy, and, in contrast to the 2001 and 2006 studies, considered the specimen to be representative of the species.