Homosexuality in medieval Europe

[3] In the 11th century, the Doctor of the Church, St. Peter Damian, wrote the Liber Gomorrhianus, an extended attack on both homosexuality and masturbation.

[4] He portrayed homosexuality as a counter-rational force undermining morality, religion, and society itself,[5] and in need of strong suppression lest it spread even and especially among clergy.

[6] Hildegard of Bingen, born seven years after the death of St. Peter Damian, reported seeing visions and recorded them in Scivias (short for Scito vias Domini, "Know the Ways of the Lord"[7]).

The emerging Church, which gained social and political sway by the mid-third century, had two approaches to sexuality.

For instance, the Roman tradition of forming a legal union with another male by declaring a "brother" persisted during the early medieval years.

[13] By the end of the Middle Ages, most of the Catholic churchmen and states accepted and lived with the belief that sexual behavior was, according to Natural Law[14][15][16] aimed at procreation, considering purely sterile sexual acts, i.e. oral and anal sex, as well as masturbation, sinful.

Most civil law codes had punishments for such "unnatural acts", especially in regions which were heavily influenced by the Church's teachings.

The Council of Nablus in 1120, in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, enacted severe penalties for Sodomy in the aftermath of the defeat of the Antiochene army at the Field of Blood the year before.

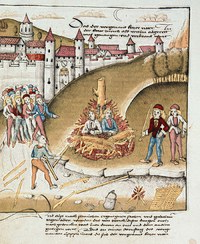

Lesbian (a term never used in the Middle Ages) behavior was punished with specific mutilations for the first two offenses and burning on the third as well.

This also led to the fact that although the Renaissance traced its origins to ancient Greece, none of the literary masters dared to publicly proclaim "males' love".

From poet German Roswitha of Gandersheim/Hrotsvitha there exist the Passio S. Pelagic, in which homosexuality as sodomy is dictated a practice of foreign lands, Arabic to be precise.

Within its content, championed was the Christian protagonist, Pelagius, for sticking to his faith against pursuits of the caliph of Cordoba, Abderrahmann, denying his embrace and becoming a martyr.

[23] Placed within the poetry of the 11th and 12th century of the medieval world laid a contradiction to the damnation of homoeroticism of the church.

As Latin was pushed into practice in the French realm, the poetry produced in this time had elements of homosexuality and Christianity.

Marbod's work as it has been studied has been found to have the most homoerotic and explicit themes, though he has been found on record denying such accusation citing his writing as more metaphorical[24] The depiction of homosexuality in art saw a rise in the Late Middle Ages, beginning with the Renaissance of the twelfth century, when Latin and Greek influences were revitalized in Europe.

[26] Noteworthy here, according to Sahar Amer, is that every stanza seems to decry the lack of a penis; Robert Clark Aldo notes "the ever-present but always absent phallus".

[28] Typically commissioned by someone of royal status, they existed as a reinventing of the ancient literary text of the bible and Greek literature.

[22] With this in mind, typically works within them that portrayed homosexual love were then reinvented to instead condemn the happening inside of the manuscript.

This is one of the earliest descriptions of lesbianism that details how early Church leaders felt about what were described as "unnatural" relations.

One such penitential that mentions the consequences for lesbian activity was the Paenitentiale Theodori, attributed to Theodore of Tarsus (the eighth Archbishop of Canterbury).

[26] Religious figures throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries continued to ignore the concept of lesbianism but in St. Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologiae discusses in his subject of lust that female homosexuality falls under one of the four categories of unnatural acts.

Some scholars argue that she was writing on behalf of a man, others that she was simply playing with the format and using the same register of affectionate language common in everyday society at the time: the poem never mentions "kissing" Mary but only praising her character, making it unclear if the "love" that Beatrice was expressing was romantic or platonic.