Cinema of Hong Kong

As a former Crown colony, Hong Kong had a greater degree of political and economic freedom than mainland China and Taiwan, and developed into a filmmaking hub for the Chinese-speaking world (including its worldwide diaspora).

Many, if not most, movie stars have recording sidelines, and vice versa; this has been a key marketing strategy in an entertainment industry where American-style, multimedia advertising campaigns have until recently been little used.

[11][page needed] In the current commercially troubled climate, the casting of young Cantopop idols (such as Ekin Cheng and the Twins) to attract the all-important youth audience is endemic.

Occasional blockbuster projects by the very biggest stars (Jackie Chan or Stephen Chow, for example) or international co-productions ("crossovers") aimed at the global market, can go as high as US$20 million or more, but these are rare exceptions.

In the hectic and low-budget industry, this method was faster and more cost-efficient than recording live sound, particularly when using performers from different dialect regions; it also helped facilitate dubbing into other languages for the vital export market (for example, Standard Mandarin for mainland China and Taiwan).

Opera scenes were the source for what are generally credited as the first movies made in Hong Kong, two 1909 short comedies entitled Stealing a Roasted Duck and Right a Wrong with Earthenware Dish.

The producer was an American, Benjamin Brodsky (sometimes transliterated 'Polaski'), one of a number of Westerners who helped jumpstart Chinese film through their efforts to crack China's vast potential market.

[19][page needed] The following year, the outbreak of World War I put a large crimp in the development of cinema in Hong Kong, as Germany was the source of the colony's film stock.

[28] The books City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema (1999) and "Yang, 2003" falsely claim that the British authorities passed a law in 1963 requiring the subtitling of all films in English, supposedly to enable a watch on political content.

[30] In Mandarin production, Shaw Brothers and Motion Picture and General Investments Limited (MP&GI, later renamed Cathay) were the top studios by the 1960s, and bitter rivals.

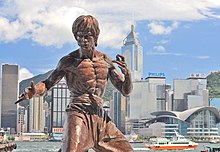

Chow and Ho landed contracts with rising young performers who had fresh ideas for the industry, like Bruce Lee and the Hui Brothers, and allowed them greater creative latitude than was traditional.

By the end of the 1970s, Golden Harvest was the top studio, signing with Jackie Chan, the kung fu comedy actor-filmmaker who would spend the next 20 years as Asia's biggest box office draw.

Such material did not suffer as much of a stigma in Hong Kong as in most Western countries; it was more or less part of the mainstream, sometimes featuring contributions from major directors such as Chor Yuen and Li Han Hsiang and often crossbreeding with other popular genres like martial arts, the costume film and especially comedy.

Director Lung Kong blended these trends into the social-issue dramas which he had already made his speciality with late 1960s Cantonese classics like The Story of a Discharged Prisoner (1967) and Teddy Girls (1969).

In the 1970s, he began directing in Mandarin and brought exploitation elements to serious films about subjects like prostitution (The Call Girls and Lina), the atomic bomb (Hiroshima 28) and the fragility of civilised society (Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (1970), which portrayed a plague-decimated, near-future Hong Kong).

[21][page needed] The brief career of Tang Shu Shuen, the territory's first noted woman director, produced two films, The Arch (1968) and China Behind (1974), that were trailblazers for a local, socially critical art cinema.

They are also widely considered forerunners of the last major milestone of the decade, the so-called Hong Kong New Wave that would come from outside the traditional studio hierarchy and point to new possibilities for the industry.

[11][page needed] The 1980s and early 1990s saw seeds planted in the 1970s come to full flower: the triumph of Cantonese, the birth of a new and modern cinema, superpower status in the East Asian market, and the turning of the West's attention to Hong Kong film.

The regional audience had always been vital, but now more than ever Hong Kong product filled theatres and video shelves in places like Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and South Korea.

[11][page needed] They even found a foothold in Japan, with its own highly developed and well-funded cinema and strong taste for American movies; Jackie Chan and Leslie Cheung were some of the stars who became very popular there.

[50][51] Other hallmarks of this era included the gangster or "Triad" movie trend launched by director John Woo, producer and long-time actor Alan Tang and dominated by actor Chow Yun-fat; romantic melodramas and martial arts fantasies starring Brigitte Lin; the comedies of stars like Cherie Chung and Stephen Chow; traditional kung fu movies dominated by Jet Li; and contemporary, stunt-driven kung fu action epitomised by the work of Jackie Chan.

[20][page needed] A definitive example of a mainstream Category III hit was Michael Mak's Sex and Zen (1991), a period comedy inspired by The Carnal Prayer Mat, the seventeenth century classic of comic-erotic literature by Li Yu.

These younger directors included names like Stanley Kwan, Clara Law and her partner Eddie Fong, Mabel Cheung, Lawrence Ah Mon and Wong Kar-wai.

[21][page needed] These artists began to earn Hong Kong unprecedented attention and respect in international critical circles and the global film festival circuit.

By the decade's end, the number of films produced in a typical year dropped from an early 1990s high of well over 200 to somewhere around 100 (a large part of this reduction was in the "Category III" softcore pornography area.

Numerous, converging factors have been blamed for the downturn: The greater access to the Mainland that came with the July 1997 handover to China, was not as much of a boom as hoped, and presented its own problems, particularly with regard to censorship.

In addition to the continuing slump, a SARS virus outbreak kept many theatres virtually empty for a time and shut down film production for four months; only fifty-four movies were made.

Successful genre cycles in the late 1990s and early 2000s have included: American-styled, high-tech action pictures such as Downtown Torpedoes (1997), Gen-X Cops and Purple Storm (both 1999), The Legend of Zu, Gen-Y Cops, The Avenging Fist (all three were released in 2001), the "Triad kids" subgenre launched by Young and Dangerous (1996–2000); yuppie-centric romantic comedies like The Truth About Jane and Sam (1999), Needing You... (2000), Love on a Diet (2001); and supernatural chillers like Horror Hotline: Big-Head Monster (2001) and The Eye (2002), often modelled on the Japanese horror films then making an international splash.

Milkyway Image, founded by filmmakers Johnnie To and Wai Ka-Fai in the mid-1990s, has had considerable critical and commercial success, especially with offbeat and character-driven crime films like The Mission (1999) and Running on Karma (2003).

[61] Critics like professor Kenny Ng and filmmaker Kiwi Chow voice concerns of its political censorship, spurring fears the new law would dampen the film industry.