Hoplite

[4] The hoplites were primarily represented by free citizens – propertied farmers and artisans – who were able to afford a linen or bronze armour suit and weapons (estimated at a third to a half of its able-bodied adult male population).

Some states maintained a small elite professional unit, known as the epilektoi or logades ('the chosen') because they were picked from the regular citizen infantry.

The Persian archers and light troops who fought in the Battle of Marathon failed because their bows were too weak for their arrows to penetrate the wall of Greek shields of the phalanx formation.

The fragmented political structure of Ancient Greece, with many competing city-states, increased the frequency of conflict, but at the same time limited the scale of warfare.

The Lacedaemonian citizens of Sparta were renowned for their lifelong combat training and almost mythical military prowess, while their greatest adversaries, the Athenians, were exempted from service only after the age of 60.

Battles were fought on level ground, and hoplites preferred to fight with high terrain on both sides of the phalanx so the formation could not be flanked.

An example of this was the Battle of Thermopylae, where the Spartans specifically chose a narrow coastal pass to make their stand against the massive Persian army.

At least in the early classical period, when cavalry was present, its role was restricted to protection of the flanks of the phalanx, pursuit of a defeated enemy, and covering a retreat if required.

[10] At this point, the phalanx would put its collective weight to push back the enemy line and thus create fear and panic among its ranks.

In earlier Homeric, Dark Age combat, the words and deeds of supremely powerful heroes turned the tide of battle.

With friends and family pushing on either side and enemies forming a solid wall of shields in front, the hoplite had little opportunity for feats of technique and weapon skill, but great need for commitment and mental toughness.

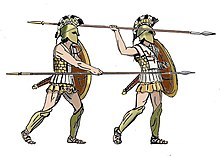

Hoplites had customized armour, the shield was decorated with family or clan emblems, although in later years these were replaced by symbols or monograms of the city states.

Their armour, also called panoply, was sometimes made of full bronze for those who could afford it, weighing nearly 32 kilograms (70 lb), although linen armor now known as linothorax was more common since it was cost-effective and provided decent protection.

By contrast with hoplites, other contemporary infantry (e.g., Persian) tended to wear relatively light armour, wicker shields, and were armed with shorter spears, javelins, and bows.

Hoplites carried a large concave shield called an aspis (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a hoplon), measuring between 80 and 100 centimetres (31 and 39 inches) in diameter and weighing between 6.5 and 8 kg (14 and 18 lb).

This very short xiphos would be very advantageous in the press that occurred when two lines of hoplites met, capable of being thrust through gaps in the shieldwall into an enemy's unprotected groin or throat, while there was no room to swing a longer sword.

[25] The large amounts of hoplite armour needed to then be distributed to the populations of Greek citizens only increased the time for the phalanx to be implemented.

[26] Rapid adoptionists propose that the double grip shield that was required for the phalanx formation was so constricting in mobility that once it was introduced, Dark Age, free-flowing warfare was inadequate to fight against the hoplites, only escalating the speed of the transition.

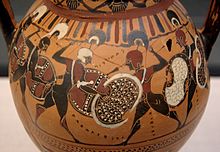

Van Wees depicts iconography found on pots of the Dark Ages believing that the foundation of the phalanx formation was birthed during this time.

Some other evidence of a transitional period lies within the text of Spartan poet Tyrtaios, who wrote, "…will they draw back for the pounding [of the missiles, no,] despite the battery of great hurl-stones, the helmets shall abide the rattle [of war unbowed]".

[28] At no point in other texts does Tyrtaios discuss missiles or rocks, making another case for a transitional period in which hoplite warriors had some ranged capabilities.

The exact time when hoplite warfare was developed is uncertain, the prevalent theory being that it was established sometime during the 8th or 7th century BC, when the "heroic age was abandoned and a far more disciplined system introduced" and the Argive shield became popular.

[29] Peter Krentz argues that "the ideology of hoplitic warfare as a ritualized contest developed not in the 7th century [BC], but only after 480, when non-hoplite arms began to be excluded from the phalanx".

[30] Anagnostis Agelarakis, based on recent archaeo-anthropological discoveries of the earliest monumental polyandrion (communal burial of male warriors) at Paros Island in Greece, unveiled a last quarter of the 8th century BC date for a hoplitic phalangeal military organization.

Fought between leagues of cities, dominated by Athens and Sparta respectively, the pooled manpower and financial resources allowed a diversification of warfare.

Often small, numbering around 6000 at its peak to no more than 1000 soldiers at lowest point,[35] divided into six mora or battalions, the Spartan army was feared for its discipline and ferocity.

These tactics inspired the future king Philip II of Macedon, who was at the time a hostage in Thebes, to develop a new type of infantry, the Macedonian phalanx.

These forces defeated the last major hoplite army, at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), after which Athens and its allies joined the Macedonian empire.

Many Greek hoplite mercenaries fought in foreign armies, such as Carthage and Achaemenid Empire, where it is believed by some that they inspired the formation of the Cardaces.

Though they mostly fielded Greek citizens or mercenaries, they also armed and drilled local natives as hoplites or rather Macedonian phalanx, like the Machimoi of the Ptolemaic army.