Horatio Alger

Horatio Alger Jr. (/ˈældʒər/; January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was an American author who wrote young adult novels about impoverished boys and their rise from humble backgrounds to middle-class security and comfort through good works.

Alger secured his literary niche in 1868 with the publication of his fourth book, Ragged Dick, the story of a poor bootblack's rise to middle-class respectability.

[4] The 14-member, full-time Harvard faculty included Louis Agassiz and Asa Gray (sciences), Cornelius Conway Felton (classics), James Walker (religion and philosophy), and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (belles-lettres).

[11] Alger's classmate Joseph Hodges Choate described Harvard at this time as "provincial and local because its scope and outlook hardly extended beyond the boundaries of New England; besides which it was very denominational, being held exclusively in the hands of Unitarians".

[14] He began reading Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, Herman Melville, and other modern writers of fiction and cultivated a lifelong love for Longfellow, whose verse he sometimes employed as a model for his own.

[16] He briefly attended Harvard Divinity School in 1853, possibly to be reunited with a romantic interest,[17] but he left in November 1853 to take a job as an assistant editor at the Boston Daily Advertiser.

[24] His first novel, Marie Bertrand: The Felon's Daughter, was serialized in the New York Weekly in 1864, and his first boys' book, Frank's Campaign, was published by A. K. Loring in Boston the same year.

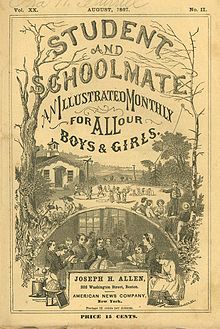

[28][29] He submitted stories to The Student and Schoolmate, a boys' monthly magazine of moral writings, edited by William Taylor Adams and published in Boston by Joseph H.

Church officials reported to the hierarchy in Boston that Alger had been charged with "the abominable and revolting crime of gross familiarity with boys".

[37] In 1866, Alger relocated to New York City where he studied the condition of the street boys, and found in them an abundance of interesting material for stories.

He attended a children's church service at Five Points, which led to "John Maynard", a ballad about an actual shipwreck on Lake Erie, which brought Alger not only the respect of the literati but a letter from Longfellow.

[42] In spite of the series' success, Alger was on financially uncertain ground and tutored the five sons of the international banker Joseph Seligman.

[44][46] He enjoyed a reunion with his brother James in San Francisco and returned to New York late in 1877 on a schooner that sailed around Cape Horn.

[44][47] He wrote a few lackluster books in the following years, rehashing his established themes, but this time the tales were played before a Western background rather than an urban one.

[44] In 1881, he wrote a biography of President James A. Garfield[44] but filled the work with contrived conversations and boyish excitements rather than facts.

Alger continued to produce stories of honest boys outwitting evil, greedy squires and malicious youths.

His literary work was bequeathed to his niece, to two boys he had casually adopted, and to his sister Olive Augusta, who destroyed his manuscripts and his letters, according to his wishes.

[65][66] Since 1947, the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans has bestowed an annual award on "outstanding individuals in our society who have succeeded in the face of adversity" and scholarships "to encourage young people to pursue their dreams with determination and perseverance".

[67] In Maya Angelou's 1969 autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, she describes her childhood belief that he was "the greatest writer in the world" and envy that all his protagonists were boys.

Ranging from the Bible and William Shakespeare (half of Alger's books contain Shakespearean references) to John Milton and Cicero, the allusions he employed were a testament to his erudition.

The first, the Rise to Respectability, he observes, is evident in both his early and his late books, notably Ragged Dick, whose impoverished young hero declares, "I mean to turn over a new leaf, and try to grow up 'spectable."

All of Alger's novels have similar plots: a boy struggles to escape poverty through hard work and clean living.

Scharnhorst writes, "Financially insecure throughout his life, the younger Alger may have been active in reform organizations such as those for temperance and children's aid as a means of resolving his status-anxiety and establish his genteel credentials for leadership.

[50] Although he continued to write for boys, Alger explored subjects like violence and "openness in the relations between the sexes and generations"; Hoyt attributes this shift to the decline of Puritan ethics in America.

Geck observes that Alger's themes have been transformed in modern America from their original meanings into a "male Cinderella" myth and are an Americanization of the traditional Jack tales.

[79] Scharnhorst writes that Alger "exercised a certain discretion in discussing his probable homosexuality" and was known to have mentioned his sexuality only once after the Brewster incident.

Alger wrote, for example, that it was difficult to distinguish whether Tattered Tom was a boy or a girl and in other instances, he introduces foppish, effeminate, lisping "stereotypical homosexuals" who are treated with scorn and pity by others.

"He learned to consult the boy in himself", Trachtenberg writes, "to transmute and recast himself—his genteel culture, his liberal patrician sympathy for underdogs, his shaky economic status as an author, and not least, his dangerous erotic attraction to boys—into his juvenile fiction".

[81] He observes that it is impossible to know whether Alger lived the life of a secret homosexual, "[b]ut there are hints that the male companionship he describes as a refuge from the streets—the cozy domestic arrangements between Dick and Fosdick, for example—may also be an erotic relationship".

Such images, Trachtenberg believes, may imply "a positive view of homoeroticism as an alternative way of life, of living by sympathy rather than aggression".