Horse culture in Mongolia

Herdsman prefer to make long journeys during seasons when horses are well fed so as to spare tired or thin animals from exertion.

An observer reported, "The animal does not appear to experience much pain during the operation, but tends to be in a state of confusion when let loose on the steppe.

Giovanni de Carpini, a Franciscan friar who visited Mongolia during the 1240s, observed that "their children begin as soon as they are two or three years old to ride and manage horses and to gallop on them, and they are given bows to suit their stature and are taught to shoot; they are extremely agile and also intrepid.

Indeed, he found that Mongols who had been to China and observed their use of horses typically came back "filled with righteous wrath and indignation over the heavy loads and cruel treatment that human beings there deal out to their animals.

The Khan instructed his general Subutai, "See to it that your men keep their crupper hanging loose on their mounts and the bit of their bridle out of the mouth, except when you allow them to hunt.

This allowed the rider greater freedom of movement; with a minimal saddle, a mounted archer could more readily swivel his torso to shoot arrows towards the rear.

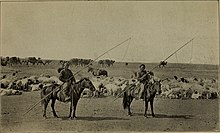

[15] The design of the stirrups makes it possible for the rider to control the horse with his legs, leaving his hands free for tasks like archery or holding a catch-pole.

"[2] The Mongols, who ride hundreds of kilometres on horseback across the roadless steppe, place a very high value on horses with a smooth gait.

The Mongol soldier relied on his horses to provide him with food, drink, transportation, armor, shoes, ornamentation, bowstring, rope, fire, sport, music, hunting, entertainment, spiritual power, and in case of his death, a mount to ride in the afterlife.

In the Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis Khan is recorded as urging his general Subutai to pursue his enemies as though they were wild horses with a catch-pole loop around their neck.

Their ability to forage beneath the snow and find their own fodder allowed the Mongols freedom to operate without long supply trains, a factor that was key to their military success.

Matthew Paris, an English writer in the 1200s, described the small steeds as, "big, strong horses, which eat branches and even trees, and which they [the Mongols] have to mount by the help of three steps on account of the shortness of their thighs."

For they are inhuman and beastly, rather monsters than men, thirsting for and drinking blood..."[24] The Mongol armies did not have long supply trains; instead, they and their horses lived off the land and the people who dwelt there.

Ibn al-Athir observed, "Moreover they [the Mongols] need no commissariat, nor the conveyance of supplies, for they have with them sheep, cows, horses, and the like quadrupeds, the flesh of which they eat, naught else.

Genghis Khan, concerned that his soldiers would use up the strength of their horses before reaching the battlefield, instructed general Subutai that he should set limits on the amount of hunting his men did.

Elizabeth Kendall observed, "These Mongolian wolves are big and savage, often attacking the herds, and one alone will pull down a good horse or steer.

[30] When the Mongols wished to conceal their movements or make themselves appear more numerous, they would sometimes tie a tree branch to their horse's tail to raise dust, obscuring their position and creating the illusion of a larger group of horsemen.

Then they tie the boat thus made to the tail of a horse, and a man swims along ahead leading it; or they sometimes have two oars, and with them they row across the water, thus crossing the river.

Since his forces did not travel on a direct beeline but made various diversions en route, the 5,000 kilometers actually translates to a horseback ride that has been estimated at 8,000 km in total length.

Elizabeth Kendall described it as follows: "Under the treaties of 1858 and 1860 a post-route between the Russian frontier and Kalgan was established, and in spite of the competing railway through Manchuria, a horse-post still crosses the desert three times a month each way.

In "The Secret History of the Mongols," it is recorded that Genghis Khan sprinkled mare's milk on the ground as a way to honor a mountain for protecting him.

The frequently recurring motif of the young foal who becomes separated from his family and must make his way in the world alone is a type of story that has been described as endemic to Mongolian culture.

They have titles like: 'The little black with velvet back,' 'The dun with lively ears,' and they are all full of touching evidences of the Mongol's love for his horses.

For example, when Jangar stops to drink at a cool stream and delights in the beauty of nature, the poet also notes that Aranjagaan grazes and enjoys a roll in the grass.

On another occasion, Sanale's red horse neighs loudly to wake his master from a deep, drunken slumber, then rebukes him for sleeping when he should be killing devils.

During an exhausting battle, Sabar's maroon horse gasps, "Master, we have fought for seven days, and I feel dizzy and giddy due to lack of food and water.

Sabar leaves the battlefield, finds fodder for his horse, takes a nap while it eats its fill, then returns to the battle and continues fighting.

Sanale is almost seduced by a hungry devil disguised as a beautiful temptress, but his horse snorts and blows up her skirt, revealing shaggy legs.

On another occasion, a different hero warns Aranjagaan that the horse will suffer a similar fate if he doesn't arrive in time to help in a critical battle.

During the communist era, Mongolian factories and mines continued to maintain herds of horses specifically for the purposes of providing airag for their workers, which was considered necessary for health and productivity.