Horses in Brittany

[21] In 1225, Alain III de Rohan donated half of Quénécan's semi-feral horses to the Abbey du Bon Repos, which he had founded near Gouarec in 1184.

[30] A few wealthy landowners made their stallions available free of charge to their farmers and sharecroppers to perpetuate the species, but the attraction of court life in Paris led to the abandonment of these stud farms.

[34] Le Boucher du Crosco, a member of Brittany's Royal Academy of Agriculture, was highly critical of Breton horses, finding them undistinguished and too small (between 1.15 m and 1.52 m[36]).

In 1689, Desclouzeaux, intendant of the Brest stud farm, spoke of the "light fines" he imposed on owners of "mediocre" bidets caught roaming and covering mares.

[39] Statistics compiled in 1690 show that 334 national stallions were distributed,[37] including 109 in the bishoprics of Saint-Pol-de-Léon, Tréguier and Nantes, resulting in the birth of 8,500 foals in the same year.

[42] In 1758, the main roads were established in the province, and in June 1776, a regular horse-drawn transport service provided stagecoach connections between various towns in Brittany.

[37] In his memoirs, the Duc d'Estrées refers to the birth of 24,000 horses each year in Brittany, and to the French government's annual investment of 30,000 pounds in this breeding program until 1717.

[50] The regulations governing the administration of provincial stud farms were published in 1717, with the preamble stating that Brittany was the region of the kingdom of France "most suitable for breeding and feeding horses".

[31] French state intervention was very strict towards local breeders, who were fined if their mares were not presented to inspectors, or if their own stallions were caught roaming free.

The 1.65 m stallions acquired abroad were unable to breed with local "bidettes" averaging 1.32 men, ruining farmers whose foals sold poorly.

On Ventôse 24, Year XII (March 14, 1804), the Morbihan Agricultural Society requested four stallions for the department, in view of the ruinous state of equine breeding.

Whereas they were left in a semi-feral state in the Léon region at the beginning of the previous century, their proximity to man coincided with the development of ploughing teams, to the detriment of oxen.

In his Traité complet de l'élève du cheval en Bretagne (1842), he testifies to the central place this animal occupies in Breton life.

[102] In 1817, as a result of Napoleon's seizures, the stallions stationed at Langonnet were on the whole very varied and of poor quality: "this is no longer a stud farm, but an acclimatization park for the world's equine fauna".

[87] The officers in charge of recruiting artillery horses discriminated against light-gray coats and favored dark-coated animals, notably imposing crossbreeding with Norman half-bloods.

[110] The Haras Nationaux, the French authority on equine breeding, is constantly at odds with Breton breeders as they try to impose their own standard for lighter horses.

[114] The addition of Arab and Thoroughbred blood to the Breton breed from the central mountains, at the instigation of the national stud farms, led to the creation of the so-called "Corlay horse" type, to supply the army cavalry.

[115] According to Yann Brekilien, "the stud farms could not tolerate the existence of equines that did not conform to official standards, and began a merciless battle against the brave bidets.

[89] In 1842, according to Houël, "Brittany's particular breed of draft horse possesses qualities that make it sought-after throughout France and abroad, for road, stagecoach, postal and artillery train services".

Some traffickers inflate the animal's rump with a bicycle pump and hypodermic needle, or introduce ginger or pepper into the anus to make them look more vigorous.

There are also techniques for calming nervous horses by tying their tongues together for the duration of the sale, or for depreciating an animal by mixing finely chopped horsehair into its food, causing it to cough.

[141] Brittany horses put to work are often given supplementary feed based on gorse, beet, rutabaga and coarse bran, cut and pounded at night.

The Haras National de Lamballe became more involved, pursuing a policy of supporting leisure breeding, much to the chagrin of Breton beef horse breeders.

[45] The differences between types of horse are due to soil and feed: the northern coast generally produces abundant food, while the central mountains offer a difficult environment for breeding.

[170] The Corlay horse is a nineteenth-century creation, and the Centre-Montagne is a descendant of the mountain bidets, which had a short official existence from 1927 to the 1980s, essentially originating in inland Brittany.

The climate, location and soil of Léon meant that the horse trade was the main source of income for its inhabitants in the mid-19th century, with each farm owning six to seven mares.

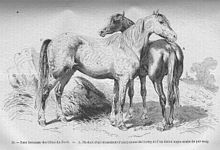

The head is square and a little heavy, the bridge of the nose straight or cambered, the gaskets pronounced, the neck thick and short, the mane often double, the withers slightly protruding and fleshy, the shoulders fleshy and slightly sloping, the rump rounded, broad, generally swallowed, hollowed out on the median line by a deep furrow, the tail set low and the manes long.

Bay-colored, sometimes dappled gray, their height varies from 1.48 m to 1.58 m. The square head is fairly light, the bridge of the nose straight and sometimes arched, the neck well proportioned, the withers quite high, the shoulders less loaded and a little more sloping than in the Leon horse, the body more elongated, the rump rounded and separated by a small furrow, the tail set higher, the limbs a little spindly compared to the other parts of the body, the fetlocks less covered with hair, the feet less splayed, less flat.

Following the publication of an article in the magazine Paysan Breton and contact with the director of the Haras National de Lamballe, an import activity began, involving a total of around one hundred animals over several years.

The Haras National de Lamballe (Côtes-d'Armor), historically created to serve the north of Brittany, is the cradle of Breton Postier breeding and a tourist site, managed by a mixed syndicate since 2006.