Hoti (tribe)

In its long history, Hoti played an important role in regional politics as a leading community in the northern Albanian tribal structure and as a semi-autonomous area in the borderlands between the Ottoman and Austrian empires and later Montenegro.

In Albania, the settlements of the region and the historical tribe are Rrapshë, Brigjë, Dacaj, Dajç, Firkuqe, Goca, Grykë, Kolçekaj, Deçkaj, Lecaj, Lulashpepaj, Peperan, Stare, Shegzë and Hot.

[5] Oral traditions and fragmentary stories were collected and interpreted by writers who travelled in the region in the 19th century about the early history of the Hoti tribe.

According to this account, the first direct male ancestor of the Hoti was Geg Lazri,[6] son of Lazër Keqi, son of a Catholic Albanian named Keq (around 1520) (according to a Hoti family tree document, the father of Keq, or Keqa, was Preka) who fleeing from Ottoman conquest settled in the Slavic-speaking area that would become the historical Piperi tribal region in what is now Montenegro.

A similar story has been collected in the area of Vasojevići, where their direct ancestor was recorded as brother of a Pipo (Piperi), Ozro (Ozrinići), Krasno (Krasniqi) and Otto (Hoti), who all fled from Herzegovina.

[8] Edith Durham in her own travels in 1908 in High Albania recorded a story about a Gheg Lazar, who arrived thirteen generations prior, fleeing from Ottoman conquest from an unknown region of Bosnia.

[9] The old man (Marash Uci) who recounted the story, did not know the date of the settlement of Hoti, but described it as after the building of the church of Gruda, which Durham matched to the year 1528.

[13] Later full translations of Ottoman defters also showed that despite chronological discrepancies and other errors, oral folk tradition was indeed based on actual historical figures.

[16] Venetian documents about the pronoia (grant) that the Hoti tribe was given over a few villages in the Shkodra area provide some more information about the early stages of this process.

[11] From this period onwards, historical records and details provide a much clearer view on the Hoti tribe, its socio-economic status and its relations with its neighbours.

Under the act of their fealty to Venice, land properties in Bratosh and Bodishë were given to them in addition to the pronoia in Podgora, which provided the pastoral mountaineers with access to grain and wine.

As Hoti was only nominally under Balša III in a border region between him and Venice, this influenced the balance of power and was also one of the events that preluded the Second Scutari War two years later.

The self-governing rights of northern Albanian tribes like Hoti and Kelmendi increased when their status changed from florici to derbendci, a position which required only nominal recognition of central authority.

Its military and political counterpart were the meetings of tribes in northern Albania and Montenegro in order to discuss cooperation against the Ottomans under the banner of one of the Catholic powers.

One such meeting, the Convention of Kuçi, was held on 15 July 1614 in Kuči, where that tribe, Hoti, Kelmendi and others decided to ask papal aid against the Ottomans as was reported by the patrician of Kotor, Francesco Bolizza.

Such an assembly is reported also in 1658, when the seven tribes of Kuči, Vasojevići, Bratonožići, Piperi, Kelmendi, Hoti and Gruda declared their support for the Republic of Venice, establishing the so-called "Seven-fold barjak" or "alaj-barjak", against the Ottomans.

In regard to villages of Hoti, he also noted, "30 houses - Tusi (Tuz), commanded by Gie Giecco (Gje Gjeko), 70 men in arms."

Additionally, in regard to villages of Roman rite, "212 houses - Hotti (Hoti), commanded by Maras Pappa (Marash Papa), 600 men in arms.

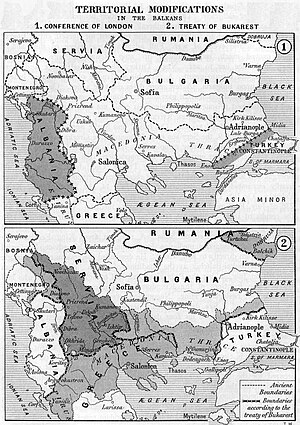

In April 1880, Italy suggested that the Ottoman Empire give Montenegro the Tuz district with its Catholic Gruda and Hoti populations that would have left the tribes split between both countries.

To help the defenders of Ulcinj, Hoti and Gruda decided to attack Montenegrin positions and captured Mataguži on July 12, but lost control over it eleven days later.

[34] Ded Gjo Luli of Hoti, Smajl Martini of Gruda and Dod Preçi of Kastrati did not surrender and hid in the mountains as fugitives.

As Nicholas made more and more open statements about annexation under Montenegro and was also called upon by the Great Powers to remain neutral and not risk a general war, the rebels chose to move forwards and start the attack on March 24, 1911.

Seven rebels from Koja and thirty Ottomans died in the battle but it became known because after victory was secured, Ded Gjo Luli raised the Albanian standard on the peak of Bratila.

The phrase Tash o vllazën do t’ju takojë të shihni atë që për 450 vjet se ka pa kush (Now brothers you have earned the right to see that which has been unseen for 450 years) has been attributed to Ded Gjo Luli by later memoirs of those who were present when he raised the flag.

[34][38] Hoti's representation included Ded Gjo Luli and Gjeto Marku and its three parish priests, Karl Prenushi (Vuksanlekaj), Sebastian Hila (Rrapsha) and Luigj Bushati (Traboin).

In the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the Albanian delegation at first headed by Turhan Pasha and then Luigj Bumçi presented their case for Hoti and other territories to be returned to Albania, but borders remained unchanged.

In this political context, documents from the British Foreign Office describe a situation where, from Hoti and Grude in what used to be Montenegro, right along the Yugoslav frontier down to Dibra and Ochrida, no inconsiderable area and population await the crusade of an Albanian or Italian Liberator..[42] Yugoslavia's capitulation to Germany in WWII led to a reshaping of borders and Hoti became a part of Albania under Italian and later German hegemony in 1941–4 to win support for the Axis among Albanians.

He annually funded the feast of St. John the Baptist (Albanian: Shën Gjoni or Shnjoni), the patron saint of Hoti, and observed mass on that day.

[46] From Pjetër Gega, founder of Traboin, trace their descent: Gjelaj, Gojçaj, Dedvukaj, Nicaj, Lekvukaj, Camaj, Gjokë-Camaj, Dushaj, Dakaj.

From Junç Gega trace their descent: Lucgjonaj (the bajraktars of Hoti from whom the Çunmulaj descend), Frangaj, Dojanaj, Palaj, Çekaj, Gegaj, Prekaj.