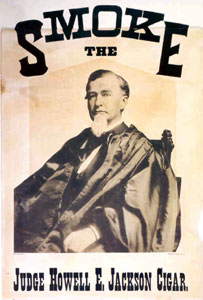

Howell E. Jackson

Howell Edmunds Jackson (April 8, 1832 – August 8, 1895) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1893 until his death in 1895.

His brief tenure on the Supreme Court is most remembered for his opinion in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., in which Jackson argued in dissent that a federal income tax was constitutional.

While on the circuit court, he sided with businesses in a major antitrust dispute and supported an expansive view of constitutional freedoms in a civil rights case.

Shortly after President Harrison – Jackson's former Senate colleague – lost reelection, Supreme Court Justice Lucius Q. C. Lamar died.

Not long after assuming office, Jackson developed tuberculosis, preventing him from playing a major role in Supreme Court affairs.

While Jackson's opinion in Pollock kept him from total obscurity in the annals of history, the journey to Washington also worsened his health considerably: he died on August 8, 1895, only eleven weeks after the ruling was handed down.

[7]: 317 Judge West H. Humphreys appointed Jackson to enforce Confederate sequestration law in western Tennessee, placing him in charge of confiscating and selling the property of Union loyalists.

[8]: 357–359 Extant newspaper accounts show Jackson auctioned off a wide variety of property, including almonds, pickles, chairs, alcohol, tobacco and dried peaches.

[8]: 362 Arguing that his role in the Confederate civil service was small, Jackson claimed in his petition that no formal sequestration orders had ever been issued under his tenure.

[12]: 407 In 1875, however, he was appointed a judge of the temporary Court of Arbitration for Western Tennessee, which heard cases stemming from the large backlog created by the Civil War.

[10]: 340 After the legislature's session began in January 1881, he was appointed by Speaker Henry B. Ramsey to the finance, ways and means; judiciary; penitentiary; public grounds and buildings; incorporations; and privileges and elections committees.

[4]: 69 Incumbent Senator James E. Bailey's state-credit policies alienated the low-tax faction of the Democratic caucus, but Republican candidate Horace Maynard also failed to garner majority support.

[17] After a special election, he was succeeded later in the month by Hugh C. Anderson, who represented the district composed of Haywood, Hardeman, and Madison counties in the previous legislative session.

[20]: 106 Cleveland asked his friend Jackson, who was still serving in the Senate, to recommend potential replacements, but the President ignored his advice and instead offered the seat to him.

[22]: 37–38 Jackson's narrow interpretation of the Act set the stage for later consequential antitrust cases, including United States v. E. C. Knight Co. (1895), and it continued to influence interstate commerce law for half a century.

[10]: 343 A lower federal court threw out the indictments, holding the officers were not exercising any legally protected civil right while they were carrying out their duties.

[10]: 342 At this point, President Harrison was a lame duck: Grover Cleveland had won the 1892 presidential election and would take office in six weeks.

[20]: 109 Not long after Lamar's death, Justice Brown, whom Jackson had recommended to Harrison a few years prior, paid a visit to the White House.

[25]: 40 Professor Richard D. Friedman concludes their acquiescence was understandable: Democrats "could not very well vote against one of their own", while "Republicans, after initial disgruntlement, understood the logic of Harrison's move.

"[25]: 40–41 Chief Justice Melville Fuller swore in Jackson on the morning of March 4, just hours before administering the presidential oath to Harrison's successor.

[26]: 285––286 When Jackson suggested he could return to Washington, the Court agreed to rehear the case to make a more conclusive ruling on the income tax's legality.

[10]: 338 Experts were uncertain how he would rule: his Southern background suggested he might support the tax, but his pro-business judicial views meant he might be inclined to strike it down.

[20]: 118 During the three days of arguments, lawyers aimed their contentions at the violently coughing Jackson, often ignoring other justices in their zeal to persuade the swing vote.

[26]: 286 Jackson joined Brown and justices John Marshall Harlan and Edward Douglass White in dissenting from the Court's holding.

[20]: 118–119 Numerous coughing fits interrupted Jackson's ardent turns of phrase, stopping the seriously ill justice several times during his forty-five-minute delivery of the dissent.

[3]: 243 Newspapers at the time identified George Shiras as the "vacillating Justice"; biographer Willard King notes that "great obloquy was heaped on him" by outlets that opposed the Court's decision.

[28]: 220 Jackson's dissent eventually won vindication from the court of history: the Sixteenth Amendment passed eighteen years after Pollock revised the Constitution to authorize an income tax.

[10]: 345 Finally, he joined a five-justice majority in Fong Yue Ting v. United States (1893) to hold the federal government could deport Chinese immigrant laborers without providing them with due process protections.

[10]: 337 The journey did substantial harm to Jackson's health, and Schiffman notes that his failure in Pollock "provided little incentive with which to uplift the spirit beyond the pains of the body".

[19]: 217 Scholar Roger D. Hardaway, while conceding that the justice "is not a giant" in the annals of the Supreme Court, argues that Jackson's accomplished if brief work deserves a prominent place in Tennessee history.