Hubbert peak theory

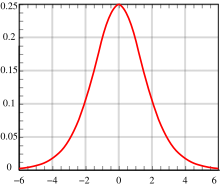

The Hubbert peak theory says that for any given geographical area, from an individual oil-producing region to the planet as a whole, the rate of petroleum production tends to follow a bell-shaped curve.

The Hubbert peak theory is based on the observation that the amount of oil under the ground in any region is finite; therefore, the rate of discovery, which initially increases quickly, must reach a maximum and then decline.

[1][2] The theory is named after American geophysicist M. King Hubbert, who created a method of modeling the production curve given an assumed ultimate recovery volume.

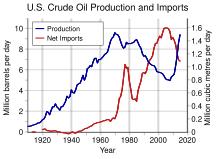

Oil production peaked at 10.2 million barrels (1.62×10^6 m3) per day in 1970 and then declined over the subsequent 35 years in a pattern that closely followed the one predicted by Hubbert in the mid-1950s.

Production from Wells utilizing these advances extraction techniques, exhibit a rate of decline far greater than traditional means.

Based on his theory, in a paper[4] he presented to the American Petroleum Institute in 1956, Hubbert correctly predicted that production of oil from conventional sources would peak in the continental United States around 1965–1970.

Hubbert further predicted a worldwide peak at "about half a century" from publication and approximately 12 gigabarrels (GB) a year in magnitude.

In a 1976 TV interview[5] Hubbert added that the actions of OPEC might flatten the global production curve but this would only delay the peak for perhaps 10 years.

reaches the half of the total available resource: The Hubbert equation assumes that oil production is symmetrical about the peak.

This process allows the for an outward manipulation of the curve, simply by purposefully neglecting to rework the well until the operator's desired market conditions are present.

He concluded that the ultimate recoverable oil resource of the contiguous 48 states was 170 billion barrels, with a production peak in 1966 or 1967.

Neither is there any reason to assume that the peak will occur when half the ultimate recoverable resource has been produced; and in fact, empirical evidence appears to contradict this idea.

The assumption of inevitable declining volumes of oil and gas produced per unit of effort is contrary to recent experience in the US.

The peaking of global oil along with the decline in regional natural gas production may precipitate this agricultural crisis sooner than generally expected.

Dale Allen Pfeiffer claims that coming decades could see spiraling food prices without relief and massive starvation on a global level such as never experienced before.

In a paper in 1956,[32] after a review of US fissionable reserves, Hubbert notes of nuclear power: There is promise, however, provided mankind can solve its international problems and not destroy itself with nuclear weapons, and provided world population (which is now expanding at such a rate as to double in less than a century) can somehow be brought under control, that we may, at last, have found an energy supply adequate for our needs for at least the next few centuries of the "foreseeable future.

[33] Technologies such as the thorium fuel cycle, reprocessing and fast breeders can, in theory, extend the life of uranium reserves from hundreds to thousands of years.

[41] Lithium availability is a concern for a fleet of Li-ion battery using cars but a paper published in 1996 estimated that world reserves are adequate for at least 50 years.

The total global mine supply has dropped by 10 percent as ore quality erodes, implying that the roaring bull market of the last eight years may have further to run.

Output fell a further 14 percent in South Africa in 2008 as companies were forced to dig ever deeper – at greater cost – to replace depleted reserves.

Lands, perceived as marginal because of remoteness, but with very high phosphorus content, such as the Gran Chaco[51] may get more agricultural development, while other farming areas, where nutrients are a constraint, may drop below the line of profitability.

This turns much of the world's underground water[53] and lakes[54] into finite resources with peak usage debates similar to oil.

[58] However, the authors reanalyzed their data with better calibrations and found plankton abundance dropped globally by only a few percent over this time interval (Boyce et al. 2014) Economist Michael Lynch[59] argues that the theory behind the Hubbert curve is simplistic and relies on an overly Malthusian point of view.

[61][62] Leonardo Maugeri, vice president of the Italian energy company Eni, argues that nearly all of peak estimates do not take into account unconventional oil even though the availability of these resources is significant and the costs of extraction and processing, while still very high, are falling because of improved technology.

He also notes that the recovery rate from existing world oil fields has increased from about 22% in 1980 to 35% today because of new technology and predicts this trend will continue.

[64] Edward Luttwak, an economist and historian, claims that unrest in countries such as Russia, Iran and Iraq has led to a massive underestimate of oil reserves.

[65] The Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas (ASPO) responds by claiming neither Russia nor Iran are troubled by unrest currently, but Iraq is.

[66] Cambridge Energy Research Associates authored a report that is critical of Hubbert-influenced predictions:[67] Despite his valuable contribution, M. King Hubbert's methodology falls down because it does not consider likely resource growth, application of new technology, basic commercial factors, or the impact of geopolitics on production.

[69] Alfred J. Cavallo, while predicting a conventional oil supply shortage by no later than 2015, does not think Hubbert's peak is the correct theory to apply to world production.

According to some economists, though, the amount of proved reserves inventoried at a time may be considered "a poor indicator of the total future supply of a mineral resource.