Hubert Humphrey 1968 presidential campaign

Johnson withdrew after an unexpectedly strong challenge from anti-Vietnam War presidential candidate, Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, in the early Democratic primaries.

Nixon led in most polls throughout the campaign, and successfully criticized Humphrey's role in the Vietnam War, connecting him to the unpopular president and the general disorder in the nation.

Humphrey experienced a surge in the polls in the days prior to the election, largely due to incremental progress in the peace process in Vietnam and a break with the Johnson war policy.

In 1960, he mounted a full-scale run, winning primaries in South Dakota and Washington D.C.; ultimately losing the Democratic nomination to Massachusetts Senator and future President John F. Kennedy.

As vice president, Humphrey oversaw turbulent times in America, including race riots and growing frustration and anger over the large number of casualties in the Vietnam War.

Late in 1967, building upon anti-war sentiment, Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota entered the race with heavy criticism of the President's Vietnam War policies.

[9] That task proved difficult following the Tet Offensive, which despite being a tactical victory, resulted in the deaths of thousands of American and South Vietnamese soldiers.

[10] The offensive included an invasion of the United States Embassy in Saigon,[11] which changed the American public perception of North Vietnamese strength and the projected length of the war.

[19] A week prior to the primary, on March 31, the President publicly announced he would not seek or accept the Democratic Party nomination,[20] thus setting the stage for Humphrey's presidential run.

His aides Max Kampelman and Bill Connell began to set up an organization and held meetings with Humphrey and his advisors, encouraging him to start a campaign.

[28] Governors Harold Hughes of Iowa and Philip H. Hoff of Vermont, each advised Humphrey to resign as vice president to separate himself from Johnson, but he declined.

The President advised Humphrey that his biggest obstacle as a candidate would be money and organization, and that he must focus on the Midwest and Rust Belt states in order to win.

Labor Secretary W. Willard Wirtz, White House staffers Harry McPherson and Charles Murphy, and journalists Norman Cousins and Bill Moyers all contributed to the speech.

Republicans, feeling that the Vice President might be the nominee, began to attack him, describing his positions as socialistic and reminding voters that Southern Democrats once considered him a "wild-eyed liberal".

[40] He won his largest share of delegates during a six-week period after May 10, when the Vietnam War was briefly removed as a campaign issue due to the delicate peace talks with Hanoi.

[44] The next month, Humphrey's rival Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles, prompting the Vice President to return to his home in Minnesota and "think about the next stage".

Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson described the response as ironic, given that Humphrey was booed at the 1948 Democratic National Convention after advocating a civil rights plank.

[43] At the end of June, Republican Senator Mark Hatfield of Oregon assessed the race, arguing that Humphrey would be the party's nominee for president but criticized him for being too closely aligned with Johnson's policies.

[57] As former Vice President Richard Nixon gained the Republican Party nomination, Humphrey held what he thought was a private meeting with 23 college students in his office.

[46] On August 10, just two weeks prior to the convention opening, South Dakota Senator George McGovern entered the race, casting himself as the standard-bearer of the Robert Kennedy legacy.

[52] Humphrey also narrowly won the party plank in support of the Vietnam War, although his officials pleaded with Johnson to accept a compromise with the doves, which he refused.

[68] Observers noted the selection of the Senator, active in civil rights and labor and on neither side of the war issue, was a move to appeal to liberals while not upsetting establishment Democrats.

[77] In Missouri, in preparation for a meeting with former President Harry Truman, Muskie tried to defend his running mate from connections made by the Nixon campaign to the Johnson administration.

[78] Muskie was renowned for his speaking ability, and was known to turn around hostile crowds including one well publicized event when he asked an anti-war protester to join him on the stage.

[5] On September 30, hoping to separate himself from the policies of the Johnson administration at the advice of O'Brien who noted that he needed the anti-war vote to win in New York and California,[82] Humphrey delivered a televised speech in Salt Lake City to a nationwide audience, and announced that if he was elected, he would put an end to the bombing of North Vietnam, and called for a ceasefire.

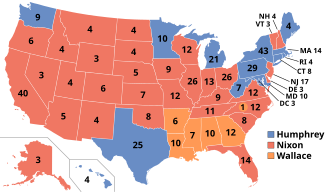

[93] Both the Humphrey and Nixon campaigns were concerned that Wallace would take a sizable number of states in the electoral college and force the House of Representatives to decide the election.

Humphrey, with Muskie by his side, fielded questions from a live studio audience and a phone bank of celebrities including Frank Sinatra and Paul Newman.

The Nixon telecast featured no interaction with anyone other than sports personally Bud Wilkinson who read queries from index cards beside rows of volunteers taking calls.

Nixon tried to reverse Humphrey's boost from the bombing halt by stating that he had been advised that "tons of supplies"[103] were being sent along the Ho Chi Minh Trail by the North Vietnamese, a shipment that could not be stopped.

[106] This discrepancy was connected to the tough Democratic primary election that caused some former McCarthy, Kennedy or McGovern supporters to vote for Nixon or Wallace as a protest.