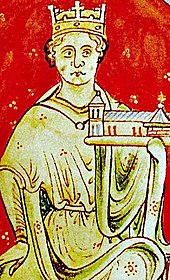

Hubert Walter

Hubert Walter (c. 1160 – 13 July 1205) was an influential royal adviser in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries in the positions of Chief Justiciar of England, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor.

Walter was not noted for his holiness in life or learning, but historians have judged him one of the most outstanding government ministers in English history.

Walter served King Henry II of England in many ways, not just in financial administration, but also including diplomatic and judicial efforts.

Modern historians have discounted this, as the list also includes benefactors, not just students; other evidence points to the fact that Walter had a poor grasp of Latin, and did not consider himself to be a learned man.

[1][b] The medieval chronicler Gervase of Canterbury said that during Henry II's reign, Walter "ruled England because Glanvill sought his counsel".

[15] At the same time he was administering York, Walter founded a Premonstratensian house of canons on purchased property at West Dereham, Norfolk in 1188.

[17] In 1187 Walter, along with Glanvill and King Henry II, attempted to mediate a dispute between the Archbishop of Canterbury, Baldwin of Forde, and the monks of the cathedral chapter.

The dispute centred on the attempt by Baldwin to build a church dedicated to Saint Thomas Becket, just outside the town of Canterbury.

The elevation of so many new bishops was probably meant to signal the new king's break with his father's habit of keeping bishoprics empty to retain the revenues of the sees.

[31] Walter subsequently led the English army back to England after Richard's departure from Palestine, but in Sicily he heard of the king's capture, and diverted to Germany.

[4] The historian Doris Stenton wrote that the Pipe Rolls, or financial records, during Walter's time as justiciar "give the impression of a country taxed to the limit".

[45] Walter's chief administrative measures were his instructions to the itinerant justices of 1194 and 1198, his ordinance of 1195, an attempt to increase order in the kingdom, and his plan of 1198 for the assessment of a land tax.

[47] Although he probably did not take part in the decision to set up a special exchequer for the collection of Richard's ransom, Walter did appoint the two escheators,[48] or guardians of the amounts due,[49] who were Hugh Bardulf in the north of England and William of Sainte-Mère-Eglise in the south.

[4][53] Walter was probably the originator of the custom of keeping an archival copy of all charters, letters, patents and feet of fines, or record of agreements reached in the royal courts, in the chancery.

His use of the knights, who appear for the first time in political life, is the first sign of the rise of this class who, either as Members of Parliament (MPs) or justices of the peace, later became the mainstay of English government.

[64] At the monastic cathedral of Worcester, he disciplined the monks between the death of Henry de Sully and the election of John of Coutances, as was his right as the archbishop of the province.

He promised that the new foundation's canons would not be allowed to vote in archiepiscopal elections nor would the body of Saint Thomas Becket ever be moved to the new church, but the monks of his cathedral chapter were suspicious and appealed to the papacy.

[68] Another council was held at London in 1200 to legislate the size and composition of clerical retinues,[69] and also ruled that the clergy, when saying Mass, should speak clearly and not speed up or slow down their speech.

[4][73] A dispute in December 1197, over Richard's demand that the magnates of England provide 300 knights to serve in France, led to renewed grumbling among the clergy and barons.

[76] On 27 May 1199 Walter crowned John, supposedly making a speech that promulgated, for the last time, the theory of a king's election by the people.

W. L. Warren, historian and author of a biography of John, says of Walter that "No one living had a firmer grasp of the intricacies of royal government, yet even in old age his mind was adaptable and fecund with suggestions for coping with new problems.

[55][78] In his relations with other officers, Walter worked closely with the justiciar Geoffrey Fitz Peter, on the collection of taxation, and both men went to Wales in 1203 on a diplomatic mission.

[4] Another joint action of the two men concerned a tax of a seventh part of all movables collected from both lay and ecclesiastical persons.

[12] In 1201 Walter went on a diplomatic mission to Philip II of France, which was unsuccessful, and in 1202 he returned to England as regent while John was abroad.

This council set forth 14 canons, or decrees, which dealt with a number of subjects, including doctrinal concerns, financial affairs, and the duties of the clergy.

[97] Walter was not a holy man, although he was, as John Gillingham, a historian and biographer of Richard I, says, "one of the most outstanding government ministers in English History".

[99] The studies of James Holt and others have shown that Richard was highly involved in government decisions, and that it was more a partnership between the king and his ministers.

[102] Walter was the butt of jokes about his lack of learning,[103] and was the target of a series of tales from the pen of the chronicler Gerald of Wales.

[105] Walter employed several canon lawyers who had been educated at Bologna[106] in his household, including John of Tynemouth, Simon of Southwell,[107] and Honorius of Kent.

[111] W. L. Warren advances the theory that either Walter or Geoffrey Fitz Peter, instead of Ranulf Glanvill, was the author of Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Angliae, a legal treatise on the laws and constitutions of the English.