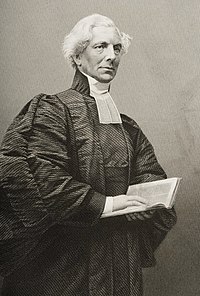

Hugh M'Neile

[8] M‘Neile was an influential, well-connected demagogue, a renowned public speaker, an evangelical cleric and a relentless opponent of "Popery",[9] who was permanently inflamed by the ever-increasing number of Irish Roman Catholics in Liverpool.

[13] Hugh Boyd M‘Neile, the younger son of Alexander M'Neile (1762–1838) and Mary M'Neile, née McNeale (?-1852), was born at Ballycastle, County Antrim on 17 July 1795, just three years before the Irish Rebellion of 1798; and, in 1798, M‘Neile was taken by his mother from Ballycastle to relatives in Scotland, in an open boat, to escape the dangers and atrocities of "the troubles" associated with the Irish Rebellion (Boyd, 1968).

M‘Neile's father owned considerable property (including the large farm at Collier's Hall), was a Justice of the Peace and served as the High Sheriff of the County of Antrim.

He almost completed his terms there as well when, around 1819, he decided to abandon the law as well as the political career that his family had anticipated for him and return to his studies in order to qualify for ordination.

In those days, Sarah Siddons, her brother John, and Eliza O'Neill (later Lady Wrixon-Becher) – all favourites of M‘Neile – were at their peak; and his later platform and pulpit performances drew very heavily on their example.

[30] Following his theological studies, M‘Neile was ordained in 1820 by his future father-in-law, William Magee (1766–1831) – who, at that time, was the Church of Ireland's Bishop of Raphoe – and served as a curate in Stranorlar, County Donegal from 1820 to 1821.

[32] Each of the Albury Conferences involved days full of close and laborious study of the prophetical books of the Bible; attempting to seek out as-yet-unfulfilled prophecies within them.

[34] In relation to the reputed prophecy, glossolalia and healing, M‘Neile became increasingly torn between his own developing view that they were not of the Holy Spirit of and his desire to remain loyal to Drummond who thought that they were.

Further, he most strongly objected "[that] it was not of God" when a female at one of Drummond's prayer sessions, which M‘Neile had "attended reluctantly", spoke in tongues – and, thus, "contradicting the biblical injunction against women teaching in church".

Prominent among them were the doctrine of the real presence in the Eucharist, the use of wafer bread, mixing water and wine in the chalice during the service, reservation, adoration, benediction, the eastward position of the celebrant, and the wearing of vestments including albs, chasubles and coloured stoles.

[36] Once installed at St Jude's, M‘Neile's eloquence attracted the attention of the Bishop of Chester – John Sumner (1780–1862), later Archbishop of Canterbury – who appointed him as an honorary canon of his cathedral.

Later, at St Paul's, a 2,000 plus seat church specifically built for him and consecrated on 2 March 1848 by John Bird Sumner, then Archbishop of Canterbury elect (it closed in 1974) he enjoyed a large income.

Individual Roman Catholics were not to be persecuted, because, in his view, they were victims of a cruel deception who needed the love and compassion of Christians to help them find true religion.

He also received £1,500 per annum in pew rents: "He had a large following, and his capacity to imbue popular prejudice against Roman Catholicism with the dignity of a spiritual crusade gave him enormous and explosive influence on Merseyside.

In April 1845, when speaking in the House of Commons on the Maynooth Endowment Bill, Thomas Macaulay characterized M‘Neile as "the most powerful representative of uncompromising Protestant opinion in the country" (McNeile, 1911, p. 265).

"[43] A "big, impetuous, eloquent Irishman with a marvellously attractive personality and a magnificent voice",[44] he had a considerable influence on the developing religious and political life of Liverpool: When he came to be Curate-in-charge of St. Jude's in 1834, the Town Council had just decided that the Corporation schools should no longer be opened with prayer, that the Bible should be banished, and a book of Scripture Extracts substituted, taken largely from the Douay [rather than the King James] Version, and that no further religious instruction should be given during schoolhours.

A circular to the parents next persuaded them to withdraw their children; and north and south the Corporation schools were left almost empty, while the temporary buildings which the Churchmen had taken were crowded to the doors.

New schools began to arise as fast as sites could be found, and the Town Council with its great majority had to own itself defeated by one who was almost a perfect stranger to the city.

The defeat of the Liberal parliamentary candidates in the general election of 1837, followed by a long period of Conservative predominance in Liverpool politics, was largely due to his influence.

[42] But with all our respect and admiration for Dr. M‘Neile, we do not consider him to be a deep thinker: there is great talent, but little profundity, in his verbal discourses; and, popular as he is, we venture to say that he shines less in the pulpit than on the platform.

[On the platform] he is at home; for, released from those trammels which the clergyman must feel around him in the pulpit, he can give a loose rein to his impetuous temper, and allow his eloquence to take broader and bolder flights.

Who that has seen him on the platform of Exeter Hall, and there witnessed his form dilate, and his eye kindle, as he launched forth the thunderbolts of his eloquent indignation against the Romish Church, will not agree with us in thinking that, great as he is in his church at Liverpool, he is still greater as the orator of the public meeting … "His eloquence was grave, flowing, emphatic – had a dignity in delivery, a perfection of elocution, that only John Bright equalled in the latter half of the 19th century.

[51] His sermons routinely lasted 90 minutes;[52] and were never measured, structured appeals to reason – they were outright, impassioned histrionic performances intentionally directed at the emotions of his audience: M‘Neile was well known for his flawed hermeneutics; viz., his inaccurate interpretation of Biblical texts.

[57] Within his sermon – regarded, overall, as a "most melancholy, wretched, and most degrading composition"[58] – M‘Neile moved to speak of "The Prince in all his beauty", mapping Prince Albert's laying of a foundation stone onto a text from Isaiah (33:17) "Thine eyes shall see the King in his beauty"[59] There were many protests at his equation of "the Saviour of the world" with a "colonel of hussars" and his implicit assertion that Albert held "title-deeds to… divinity" (Anon, 1847h).

[62] On the morning of 8 December 1850, when throwing "thunderbolts" at one of his favourite targets, the evils of the Roman Catholic confessional,[63] M‘Neile made a series of outrageous statements of which, immediately after his sermon had been delivered, he denied any knowledge of ever having uttered; and, for which he specifically apologized at the evening service, and withdrew without reservation, as the following newspaper account relates: The frenzied vehemence of bigotry has reached its climax.

Dr. M‘Neile, the notorious platform orator, uttered a sentence last Sunday morning, in the pulpit in St. Paul’s Church, Prince’s Park, which, we are sure, was never surpassed by the cruel ferocity of Popish intolerance, in the worst days of the Inquisition.

Dr. M‘Neile, on the same Sunday evening, went into his reading desk, and pronounced before his congregation the following apology:— In 1851, these events were also presented as a classic example of "the dangers of extempore preaching" (Gilbert, 1851, p. 10).

[72] M'Neile was in close sympathy with the philanthropic work, as well as the religious views, of the Earl of Shaftesbury, who tried hard to persuade Lord Palmerston to make him a bishop.

You must be aware how desirous the Queen is generally to sanction the recommendations you make for the disposal of the patronage of the Crown, and that it is most unwillingly her Majesty demurs on the present occasion.

The Queen would ask whether his appointment is not likely to stir up a considerable amount of ill-feeling among the Roman Catholics, and in the minds of those who sympathise with them, which will more than counter-balance the advantage to be gained by the promotion of an able advocate of the Royal supremacy.