Huia

[3] It was already a rare bird before the arrival of Europeans, confined to the Ruahine, Tararua, Rimutaka and Kaimanawa mountain ranges in the south-east of the North Island.

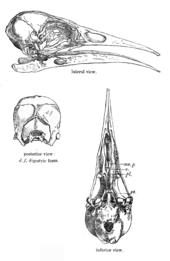

[4][5] It was remarkable for its pronounced sexual dimorphism in bill shape; the female's beak was long, thin and arched downward, while the male's was short and stout, like that of a crow.

The huia is one of New Zealand's best-known extinct birds because of its bill shape and beauty, as well as its special place in Māori culture and oral tradition.

[10] A molecular study of the nuclear RAG-1 and c-mos genes of the three species within the family proved inconclusive, the data providing most support for either a basally diverging kōkako or huia.

[16][4] Immature huia had small pale wattles, duller plumage flecked with brown, and a reddish-buff tinge to the white tips of the tail feathers.

The difference was not only in the bone; the rhamphotheca grew way past the end of the bony maxilla and mandible to produce a pliable implement able to deeply penetrate holes made by wood-boring beetle larvae.

[13] Subfossil deposits and midden remains reveal that the huia was once widespread in both lowland and montane native forest throughout the North Island,[4] extending from the northernmost tip at Cape Reinga[5] to Wellington and the Aorangi Range in the far south.

[5] The huia vanished from the northern and western North Island following Māori settlement in the 14th century, due to over-hunting, forest clearance, and introduced kiore preying on nests.

The species was observed in native vegetation including mataī (Prumnopitys taxifolia), rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum), kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides), northern rātā (Metrosideros robusta), maire (Nestegis), hinau (Elaeocarpus dentatus), tōtara (Podocarpus totara), rewarewa (Knightia excelsa), māhoe (Melicytus ramiflorus), and taraire (Beilschmiedia tarairi), and at sea level in karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus) trees at Cape Turakirae.

[25] Like the surviving New Zealand wattlebirds, the saddleback and the kōkako, the huia was a weak flier and could only fly for short distances, and seldom above tree height.

[25] More often it would use its powerful legs to propel it in long leaps and bounds through the canopy or across the forest floor,[4] or it would cling vertically to tree trunks with its tail spread for balance.

[16] The huia, with the previously endangered saddleback, were the two species of classic bark and wood probers in the arboreal insectivore guild in the New Zealand avifauna.

Woodpeckers do not occur east of Wallace's line; their ecological niche is filled by other groups of birds that feed on wood-boring beetle larvae, albeit in rotting wood.

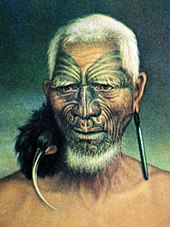

[19] In Māori culture, the "white heron and the Huia were not normally eaten but were rare birds treasured for their precious plumes, worn by people of high rank".

[15][18] Māori attracted the huia by imitating its call and then captured it with a tari (a carved pole with a noose at the end) or snare, or killed it with clubs or long spears.

[25] Although the huia's range was restricted to the southern North Island, its tail feathers were valued highly and were exchanged among tribes for other valuable goods such as pounamu and shark teeth, or given as tokens of friendship and respect.

[25] Businesses include the public swimming pool in Lower Hutt, a Marlborough winery, and Huia Publishers, which specialises in Māori writing and perspectives.

[18] After European settlement the huia's numbers began to decline more quickly, due mainly to two well-documented factors: widespread deforestation and over-hunting.

Massive deforestation occurred in the North Island at this time, particularly in the lowlands of southern Hawkes Bay, the Manawatū and the Wairarapa, as land was cleared by European settlers for agriculture.

[12][18] The destruction of this part of its habitat would have undoubtedly had a severe impact on huia populations, but its removal would have been particularly dire if they did in fact descend to the lowlands as a winter refuge to escape snow at higher altitudes[18][42] as some researchers including Oliver have surmised.

Due to its pronounced sexual dimorphism and its beauty, huia were sought after as mounted specimens by wealthy collectors in Europe[53] and by museums all over the world.

[18][25] These individuals and institutions were willing to pay large sums of money for good specimens, and the overseas demand created a strong financial incentive for hunters in New Zealand.

Austrian taxidermist Andreas Reischek took 212 pairs as specimens for the Natural History museum in Vienna over a period of 10 years,[18] while New Zealand ornithologist Walter Buller collected 18 on just one of several expeditions to the Rimutaka Ranges in 1883.

[25] While we were looking at and admiring this little picture of bird-life, a pair of Huia, without uttering a sound, appeared in a tree overhead, and as they were caressing each other with their beautiful bills, a charge of No.

The incident was rather touching and I felt almost glad that the shot was not mine, although by no means loth to appropriate 2 fine specimens.The rampant and unsustainable hunting was not just financially motivated: it also had a more philosophical, fatalistic aspect.

[55] This assumption of inevitable doom led to a conclusion that the conservation of native biota was pointless and futile; Victorian collectors instead focused their efforts on acquiring a good range of specimens before the rare species disappeared altogether.

[18] There were successive sharp declines in numbers of huia in the 1860s[7] and in the late 1880s, prompting the chiefs of the Manawatū and the Wairarapa to place a rāhui on the Tararua Range.

[25] The species was abundant in a few places in the early 20th century between Hawke's Bay and the Wairarapa;[7] a flock of 100–150 birds was reported at the summit of the Akatarawa–Waikanae track in 1905; they were still "fairly plentiful" in the upper reaches of the Rangitikei River in 1906[7] – and yet, the last confirmed sighting came just one year later.

A man familiar with the species reported seeing three huia in Gollans Valley behind York Bay (between Petone and Eastbourne on Wellington Harbour), an area of mixed beech and podocarp forest well within the bird's former range, on 28 December 1922.

[57][58] The tribe Ngāti Huia agreed in principle to support the endeavour, which would be carried out at the University of Otago, and a California-based Internet start-up volunteered $100,000 of funding.