Hujum

By abolishing Central Asian societal norms and heralding in women's liberation, the Soviets believed they could clear the way for the construction of socialism.

The campaign's purpose was to rapidly change the lives of women in Muslim societies so that they would be able to actively participate in public life, formal employment, education, and ultimately membership in the Communist Party.

[2] In contrast to how it was presented to the populace, Hujum was seen by Muslims as a campaign through which outsiders (i.e., Slavs) sought to force their cultural values onto the indigenous Turkic populations.

Thus, the veil inadvertently became a marker of cultural identity;[2] wearing it became an act of pro-Islamic political defiance as well as a sign of support for ethnic nationalism.

[2] However, over time, the campaign was a success: the rate of female literacy increased, while polygamy, honour killings, child marriages, and veiling diminished.

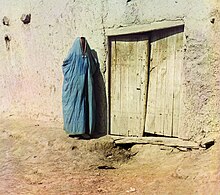

Prior to Soviet rule, Nomadic Kazakh, Kirgiz, and Turkmen women used a yashmak, a veil that covered only the mouth.

Only settled Uzbeks,Tajiks and people of Caucasus had strict veiling practices, which Tamerlane and Mongols supposedly initiated.

Cultural mores strongly condemned unveiling as it was thought to lead to premarital or adulterous sex, a deep threat to Central Asian conceptions of family honor.

Arrayed against the traditional practices stood the Jadids, elite Central Asians whose support for women's education would help spur Soviet era unveiling.

[15] The Tsarist government, while critical of veiling, kept separate laws for Russians and Central Asians in order to facilitate a peaceful, financially lucrative empire.

[16] Separate laws allowed prostitution in Russian zones, encouraging veiling as a firm way for Central Asian women to preserve their honor.

[18] Faced with this synthesis of Islamic and western practice, Central Asian women began to question, if not outright attack, veiling.

[20] Initial central control was so weak that Jadids, acting under the communist banner, provided the administrative and ruling class.

[22] Moscow did not press the case; it was more interested in reviving war-ravaged Central Asia than altering cultural norms.

Earlier, Soviet pro-nationality policies encouraged veil wearing as a sign of ethnic difference between Turkmen and Uzbeks.

In accordance with the Soviet pro-nationality policy, the TASSR was split into five republics: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

The post-Jadid, more explicitly communist government encouraged women's activism but ultimately was not strong enough to enact widespread change, either in settled or nomadic communities.

Throwing off the veil in public (an individual act of emancipation) was expected to correspond with (or catalyze) a leap upward in women's political consciousness and a complete transformation in her cultural outlook.

The campaigns aimed to completely and swiftly eradicate the veils (paranji) that Muslim women wore in the presence of unrelated males.

To eradicate the intended target (that is, the paranji), the Zhenotdel workers designated their time to organizing public demonstrations on a grand scale, where fiery speeches and inspirational tales would speak for women's liberation.

By aligning collectivization with the hujum, the idea was that the Soviets could more easily control and intervene in the everyday life of the Uzbeks.

The idea was that only after this portion of the campaign demonstrated the change in these families would it be spread to non-Communists, like trade-union members, factory workers, and schoolteachers.

They utilized the weapons of the weak: protests, speeches, public meetings, petitions against the government, or a simple refusal to practice the laws.

Some welcomed the campaign, but these supporters often faced unrelenting insults, threats of violence, and other forms of harassment that made life especially difficult.

Those brave enough to partake in the unveiling campaign were often ostracized, attacked, or even killed for their failure to defend tradition and Muslim law (shariah).

These murders were not spontaneous eruptions, but premeditated attacks designed to demonstrate that the local community held more authority over women's actions than did the state.

These laws, deeming attacks on unveiling as "counterrevolutionary" and as "terrorist acts" (meriting the death penalty),[40] were designed to help local authorities defend women from harassment and violence.

Modernization's effects were clear in Uzbekistan: education was made available for most Uzbek regions, literacy rose, and health care was vastly improved.