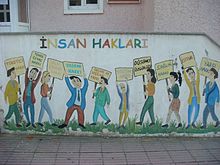

Human rights in Turkey

In March 2017, the United Nations accused the Turkish government of "massive destruction, killings and numerous other serious human rights violations" against the ethnic Kurdish minority.

Zana, who had been recognized as prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International and had been awarded the Sakharov Prize by the European Parliament, had been jailed in 1994, allegedly for being a member of the outlawed PKK, but officiously for having spoken Kurdish in public during her parliamentary oath.

[26] The mass violations of human rights in the mainly Kurdish-populated southeast and eastern regions of Turkey in the 1990s took the form of enforced disappearances and killings by unknown perpetrators which the state authorities showed no willingness to solve.

[28] A parliamentary commission to research killings by unknown perpetrators (faili meçhul cinayetleri araştırma komisyonu) was founded in 1993 and worked for about two years.

Most of the cases followed the same pattern: the missing persons had allegedly been arrested at their homes on charges of belonging to the PKK and taken to the police station but their detention was later denied by the authorities.

[4] Their communities mainly exist in Istanbul with Armenian and Greek-Orthodox Christians; in southeastern Turkey other groups like the Syriacs and Yazidi (a syncretistic faith) can be found.

According to the human rights organization Mazlumder, the military charged individuals with lack of discipline for activities that included performing Muslim prayers or being married to women who wore headscarves.

[75] On 3 July 2020, in a high-profile trial, a Turkish court sentenced the honorary chair of Amnesty International Turkey, Taner Kilic, to six years and three months in jail, accusing him for being a member of terror organization.

Human rights organizations claimed that holding individuals charged with terrorism offenses in prolonged pre-trial detention continued to be widely used in Turkey and raised concerns regarding it becoming a form of summary punishment.

One of the amendments was a revision of the criminal code that establishes sentences of up to three years in prison for “publicly disseminating false information” on digital platforms.

Her arrest was linked to a statement she made in the press on the occasion of a conference she gave in Germany on 19 October 2022, about allegations of the use of chemical weapon by Turkey in Kurdistan regional federation of Iraq.

[81] In 2017, the CPJ identified 81 jailed journalists in Turkey (including the editorial staff of Cumhuriyet, Turkey's oldest newspaper still in circulation), all directly held for their published work (ranking first in the world in 2017, with more journalists in prison than in Iran, Eritrea or China);[82] while in 2015 Freemuse identified nine musicians imprisoned for their work (ranking third in that year after Russia and China).

[84][85] The restrictions were imposed in the context of the purges that followed the coup attempt, a few weeks after a significant constitutional referendum, and following more selective partial blocking of Wikipedia content in previous years.

The purge was criticized internationally, including by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, who also condemned the coup attempt.

[91] The government has alleged affiliation with the Gülen movement or with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (also listed as a terrorist organization) as a reason for firings and arrests.

[citation needed]In a related case, journalist Perihan Mağden was tried and acquitted by a Turkish court for supporting Tarhan and advocating conscientious objection as a human right.

After serving a few months in the Armed Forces he claimed that he had experienced disrespectful interference with his religious practice, as well as indoctrination about Turkey's three-decade-old war with Kurdish insurgents.

Further instances of imprisonment included The Council of Europe and the United Nations have regularly called upon Turkey to legally recognise the right to conscientious objection.

"[106] Nevertheless, Amnesty International stated in 2009 that the right to freedom of peaceful assembly was denied, and law enforcement officials used excessive force to disperse demonstrations.

They included Idil Eser, head of Amnesty International Turkey, Peter Steudtner, a hotel owner and a Swedish and German trainee.

Activists detained included Ilknur Üstün of the Women's Coalition, lawyer Günal Kursun and Veli Acu of the Human Rights Agenda Association.

Political parties closed by the Constitutional Court For the number of associations, trade unions, political parties and cultural centres that were closed down or raided the Human Rights Association presented the following figure for the years 1999 to 2008:[121] Though Turkey is a land of vast ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity – home not only to Turks, Kurds and Armenians, but also, among others, Alevis, Ezidis, Assyrians, Laz, Caferis, Roma, Greeks, Caucasians and Jews, the history of the state is one of severe repression of minorities in the name of nationalism.

Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, some Kurdish tribes, which were still feudal (manorial) communities led by chieftains (agha), became discontent about certain aspects of Atatürk's reforms aiming to modernise the country, such as secularism (the Sheikh Said rebellion, 1925)[126] and land reform (the Dersim rebellion, 1937–1938),[127] and staged armed revolts that were put down with military operations.

[138][139] Many judgments are related to cases such as civilian deaths in aerial bombardments,[140] torturing,[141] forced displacements,[142] destroyed villages,[143][144][145] arbitrary arrests,[146] murdered and disappeared Kurdish journalists, activists and politicians.

Nevertheless, in Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia regions, older attitudes prevail among the local Kurdish, Turkish and Arab populations, where women still face domestic violence, forced marriages, and so-called honor killings.

[173] In 2008, critics have pointed out that Turkey has become a major market for foreign women who are coaxed and forcibly brought to the country by international mafia to work as sex slaves, especially in big and touristic cities.

[185] On 21 May 2008 Human Rights Watch published a 123-page report documenting a long and continuing history of violence and abuse based on sexual orientation and gender identity in Turkey.

Human Rights Watch conducted more than 70 interviews over a three-year period, documenting how gay men and transgender people face beatings, robberies, police harassment, and the threat of murder.

[197] Around a million people became displaced from towns and villages in south-eastern Turkey during the 1980s and 1990s as a result of the insurgent actions of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the counter-insurgency policies of the Turkish government.

The Labor Act of 2003 established a 45-hour workweek, banned discrimination based on sex, religion, or political affiliation, and entitlement to compensation in case of termination without valid cause.