Human rights in the Soviet Union

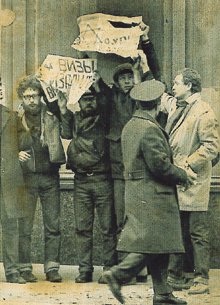

[9]: 117 Human rights activists in the Soviet Union were regularly subjected to harassment, repressions and arrests.

[8] The USSR and other countries in the Soviet Bloc had abstained from affirming the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), saying that it was "overly juridical" and potentially infringed on national sovereignty.

[15][16][17] Sergei Kovalev recalled "the famous article 125 of the Constitution which enumerated all basic civil and political rights" in the Soviet Union.

But when he and other prisoners attempted to use this as a legal basis for their abuse complaints, their prosecutor's argument was that "the Constitution was written not for you, but for American Negroes, so that they know how happy the lives of Soviet citizens are".

Defense lawyers, who had to be party members, were required to take their client's guilt for granted..."[13] In the 1930s and 1940s, political repression was widely practiced by the Soviet secret police services, OGPU and NKVD.

[20] An extensive network of civilian informants – either volunteers, or those forcibly recruited – was used to collect intelligence for the government and report cases of suspected dissent.

Art, literature, education, and science were placed under strict ideological scrutiny, since they were supposed to serve the interests of the victorious proletariat.

Many scientific disciplines, such as genetics, cybernetics, and comparative linguistics, were suppressed in the Soviet Union during some periods, condemned as "bourgeois pseudoscience".

Some scientists worked as prisoners in "Sharashkas" (research and development laboratories within the Gulag labor camp system).

Historian Robert Conquest described the Soviet electoral system as "a set of phantom institutions and arrangements which put a human face on the hideous realities: a model constitution adopted in a worst period of terror and guaranteeing human rights, elections in which there was only one candidate, and in which 99 percent voted; a parliament at which no hand was ever raised in opposition or abstention.

[26] Many forms of private trade with the intent of gaining profit were considered "speculation" (Russian: спекуляция) and banned as a criminal offense to be punished with fines, imprisonment, confiscation and/or corrective labor.

[33] All political youth organizations, such as Pioneer movement and Komsomol served to enforce the policies of the Communist Party.

Toward that end, the Communist regime confiscated church property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated atheism in the schools.

[34][35][36][37] Many Orthodox (along with peoples of other faiths) were also subjected to psychological punishment or torture and mind control experimentation in an attempt to force them give up their religious convictions (see Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union).

[35][36][38][39] Practicing Orthodox Christians were restricted from prominent careers and membership in communist organizations (e.g. the party and the Komsomol).

In the Soviet Criminal Code, a refusal to return from abroad was treason, punishable by imprisonment for a term of 10–15 years, or by death with confiscation of property.

In several cases, only the public profile of individual human rights campaigners such as Andrei Sakharov helped prevent a complete shutdown of the movement's activities.

Over the next two years the Helsinki Groups would be harassed and threatened by the Soviet authorities and eventually forced to close down their activities, as leading activists were arrested, put on trial and imprisoned or pressured into leaving the country.

In February 1987 KGB Chairman Victor Chebrikov reported to Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev that 288 people were serving sentences for offenses committed under Articles 70, 190-1 and 142 of the RSFSR Criminal Code; a third of those convicted were being held in psychiatric hospitals.

Just as glasnost did not represent "freedom of speech", so attempts by activists to hold their own events and create independent associations and political movements met with disapproval and obstruction from Gorbachev and his Politburo.

[50] As they conceded more and more of the rights over which the Communists had established their monopoly in the 1920s, events and organisations not initiated or overseen by the regime were frowned on and discouraged by the supposedly liberal authorities of the brief and ambivalent period of perestroika and official glasnost.

The authorities formed units of riot police OMON to deal with the mounting protests and rallies across the USSR.