Heterosis

[3] The physiological vigor of an organism as manifested in its rapidity of growth, its height and general robustness, is positively correlated with the degree of dissimilarity in the gametes by whose union the organism was formed … The more numerous the differences between the uniting gametes — at least within certain limits — the greater on the whole is the amount of stimulation … These differences need not be Mendelian in their inheritance … To avoid the implication that all the genotypic differences which stimulate cell-division, growth and other physiological activities of an organism are Mendelian in their inheritance and also to gain brevity of expression I suggest … that the word 'heterosis' be adopted.Heterosis is often discussed as the opposite of inbreeding depression, although differences in these two concepts can be seen in evolutionary considerations such as the role of genetic variation or the effects of genetic drift in small populations on these concepts.

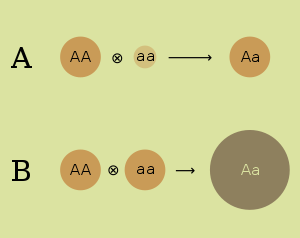

Inbreeding depression occurs when related parents have children with traits that negatively influence their fitness largely due to homozygosity.

Inbred strains tend to be homozygous for recessive alleles that are mildly harmful (or produce a trait that is undesirable from the standpoint of the breeder).

In the early 20th century, after Mendel's laws came to be understood and accepted, geneticists undertook to explain the superior vigor of many plant hybrids.

Two competing hypotheses, which are not mutually exclusive, were developed:[7] Dominance and overdominance have different consequences for the gene expression profile of the individuals.

If overdominance is the main cause for the fitness advantages of heterosis, then there should be an over-expression of certain genes in the heterozygous offspring compared to the homozygous parents.

[12] Population geneticist James Crow (1916–2012) believed, in his younger days, that overdominance was a major contributor to hybrid vigor.

[13] According to Crow, the demonstration of several cases of heterozygote advantage in Drosophila and other organisms first caused great enthusiasm for the overdominance theory among scientists studying plant hybridization.

Crow wrote: The current view ... is that the dominance hypothesis is the major explanation of inbreeding decline and [of] the high yield of hybrids.

[16] Such findings demonstrate that heterosis effects, with a genome dosage-dependent epigenetic basis, can be generated in F1 offspring that are genetically isogenic (i.e. harbour no heterozygosity).

The mechanism involves acetylation or methylation of specific amino acids in histone H3, a protein closely associated with DNA, which can either activate or repress associated genes.

Breeding between more genetically distant individuals decreases the chance of inheriting two alleles that are the same or similar, allowing a more diverse range of peptides to be presented.

Heterotic groups are created by plant breeders to classify inbred lines, and can be progressively improved by reciprocal recurrent selection.

Hybrid breeding methods are used in maize, sorghum, rice, sugar beet, onion, spinach, sunflowers, broccoli and to create a more psychoactive cannabis.

Dr. Beal's work led to the first published account of a field experiment demonstrating hybrid vigor in corn, by Eugene Davenport and Perry Holden, 1881.

Donald F. Jones at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, New Haven invented the first practical method of producing a high-yielding hybrid maize in 1914–1917.

Jones' method produced a double-cross hybrid, which requires two crossing steps working from four distinct original inbred lines.

[citation needed] Hybrid rice sees cultivation in many countries, including China, India, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

[18] Compared to inbred lines, hybrids produce approximately 20% greater yield, and comprise 45% of rice planting area in China.

The hybrid vigor produced allows the production of uniform birds at a marketable carcass weight at 6–9 weeks of age.

Results vary wildly, with some studies showing benefit and others finding the mixed breed dogs to be more prone to genetic conditions.

[29][30][31] Michael Mingroni has proposed heterosis, in the form of hybrid vigor associated with historical reductions of the levels of inbreeding, as an explanation of the Flynn effect, the steady rise in IQ test scores around the world during the 20th century, [citation needed] though a review of nine studies found that there is no evidence to suggest inbreeding has an effect on IQ.