Hyperbolic angle

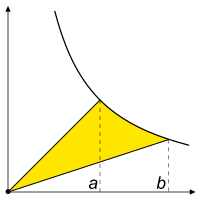

In geometry, hyperbolic angle is a real number determined by the area of the corresponding hyperbolic sector of xy = 1 in Quadrant I of the Cartesian plane.

The hyperbola xy = 1 is rectangular with semi-major axis

First define: Note that, because of the role played by the natural logarithm: Finally, extend the definition of hyperbolic angle to that subtended by any interval on the hyperbola.

By the result of Gregoire de Saint-Vincent, the hyperbolic sectors determined by these angles have the same area, which is taken to be the magnitude of the angle.

The idea of addition of angles, basic to science, corresponds to addition of points on one of these ranges as follows: Circular angles can be characterized geometrically by the property that if two chords P0P1 and P0P2 subtend angles L1 and L2 at the centre of a circle, their sum L1 + L2 is the angle subtended by a chord P0Q, where P0Q is required to be parallel to P1P2.

It thus makes sense to define the hyperbolic angle from P0 to an arbitrary point on the curve as a logarithmic function of the point's value of x.

[1][2] Whereas in Euclidean geometry moving steadily in an orthogonal direction to a ray from the origin traces out a circle, in a pseudo-Euclidean plane steadily moving orthogonally to a ray from the origin traces out a hyperbola.

In Euclidean space, the multiple of a given angle traces equal distances around a circle while it traces exponential distances upon the hyperbolic line.

[3] Both circular and hyperbolic angle provide instances of an invariant measure.

For the hyperbola the turning is by squeeze mapping, and the hyperbolic angle magnitudes stay the same when the plane is squeezed by a mapping There is also a curious relation to a hyperbolic angle and the metric defined on Minkowski space.

Just as two dimensional Euclidean geometry defines its line element as the line element on Minkowski space is[4] Consider a curve embedded in two dimensional Euclidean space, Where the parameter

The arclength of this curve in Euclidean space is computed as: If

defines a unit circle, a single parameterized solution set to this equation is

Now doing the same procedure, except replacing the Euclidean element with the Minkowski line element, and defining a unit hyperbola as

Just as the circular angle is the length of a circular arc using the Euclidean metric, the hyperbolic angle is the length of a hyperbolic arc using the Minkowski metric.

The quadrature of the hyperbola is the evaluation of the area of a hyperbolic sector.

It can be shown to be equal to the corresponding area against an asymptote.

The quadrature was first accomplished by Gregoire de Saint-Vincent in 1647 in Opus geometricum quadrature circuli et sectionum coni.

As an example of a transcendental function, the logarithm is more familiar than its motivator, the hyperbolic angle.

Nevertheless, the hyperbolic angle plays a role when the theorem of Saint-Vincent is advanced with squeeze mapping.

Circular trigonometry was extended to the hyperbola by Augustus De Morgan in his textbook Trigonometry and Double Algebra.

Clifford used the hyperbolic angle to parametrize a unit hyperbola, describing it as "quasi-harmonic motion".

In 1894 Alexander Macfarlane circulated his essay "The Imaginary of Algebra", which used hyperbolic angles to generate hyperbolic versors, in his book Papers on Space Analysis.

[7] The following year Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society published Mellen W. Haskell's outline of the hyperbolic functions.

[8] When Ludwik Silberstein penned his popular 1914 textbook on the new theory of relativity, he used the rapidity concept based on hyperbolic angle a, where tanh a = v/c, the ratio of velocity v to the speed of light.

He wrote: Silberstein also uses Lobachevsky's concept of angle of parallelism Π(a) to obtain cos Π(a) = v/c.

[9] The hyperbolic angle is often presented as if it were an imaginary number,

But in the Euclidean plane we might alternately consider circular angle measures to be imaginary and hyperbolic angle measures to be real scalars,

These relationships can be understood in terms of the exponential function, which for a complex argument

or if the argument is separated into real and imaginary parts