Hypothesis

A scientific hypothesis must be based on observations and make a testable and reproducible prediction about reality, in a process beginning with an educated guess or thought.

Working hypotheses are frequently discarded, and often proposed with knowledge (and warning) that they are incomplete and thus false, with the intent of moving research in at least somewhat the right direction, especially when scientists are stuck on an issue and brainstorming ideas.

[7] In this sense, 'hypothesis' refers to a clever idea or a short cut, or a convenient mathematical approach that simplifies cumbersome calculations.

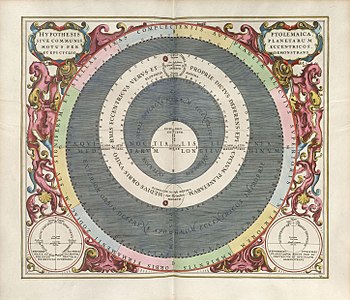

[8] Cardinal Robert Bellarmine gave a famous example of this usage in the warning issued to Galileo in the early 17th century: that he must not treat the motion of the Earth as a reality, but merely as a hypothesis.

[9] In common usage in the 21st century, a hypothesis refers to a provisional idea whose merit requires evaluation.

[clarification needed] In entrepreneurial setting, a hypothesis is used to formulate provisional ideas about the attributes of products or business models.

Karl Popper, following others, has argued that a hypothesis must be falsifiable, and that one cannot regard a proposition or theory as scientific if it does not admit the possibility of being shown to be false.

Other philosophers of science have rejected the criterion of falsifiability or supplemented it with other criteria, such as verifiability (e.g., verificationism) or coherence (e.g., confirmation holism).

The scientific method involves experimentation to test the ability of some hypothesis to adequately answer the question under investigation.

In contrast, unfettered observation is not as likely to raise unexplained issues or open questions in science, as would the formulation of a crucial experiment to test the hypothesis.

Only in such cases does the experiment, test or study potentially increase the probability of showing the truth of a hypothesis.

A trial solution to a problem is commonly referred to as a hypothesis—or, often, as an "educated guess"[14][2]—because it provides a suggested outcome based on the evidence.

[17] Like all hypotheses, a working hypothesis is constructed as a statement of expectations, which can be linked to the exploratory research purpose in empirical investigation.

Notably, Imre Lakatos and Paul Feyerabend, Karl Popper's colleague and student, respectively, have produced novel attempts at such a synthesis.

[22] Conventional significance levels for testing hypotheses (acceptable probabilities of wrongly rejecting a true null hypothesis) are .10, .05, and .01.