Film speed

A closely related system, also known as ISO, is used to describe the relationship between exposure and output image lightness in digital cameras.

Emulsions that were less sensitive were deemed "slower" as the time to complete an exposure was much longer and often usable only for still life photography.

Lower sensitivities, which require longer exposures, will retain more viable image data due to finer grain or less noise, and therefore more detail.

The Warnerke Standard Sensitometer consisted of a frame holding an opaque screen with an array of typically 25 numbered, gradually pigmented squares brought into contact with the photographic plate during a timed test exposure under a phosphorescent tablet excited before by the light of a burning magnesium ribbon.

[5] The concept, however, was later built upon in 1900 by Henry Chapman Jones (1855–1932) in the development of his plate tester and modified speed system.

The system was later extended to cover larger ranges and some of its practical shortcomings were addressed by the Austrian scientist Josef Maria Eder (1855–1944)[3] and Flemish-born botanist Walter Hecht [de] (1896–1960), (who, in 1919/1920, jointly developed their Eder–Hecht neutral wedge sensitometer measuring emulsion speeds in Eder–Hecht grades).

It grew out of drafts for a standardized method of sensitometry put forward by the Deutscher Normenausschuß für Phototechnik[10] as proposed by the committee for sensitometry of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für photographische Forschung[11] since 1930[12][13] and presented by Robert Luther [de][13][14] (1868–1945) and Emanuel Goldberg[14] (1881–1970) at the influential VIII.

Originally the sensitivity was written as a fraction with 'tenths' (for example "18/10° DIN"),[16] where the resultant value 1.8 represented the relative base 10 logarithm of the speed.

When BS 935:1941 was published during World War II, specifying exposure tables for negative materials, it employed the same fixed-density speed criterion used in the German DIN 4512:1934 system.

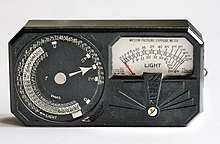

The meter and film rating system were invented by William Nelson Goodwin, Jr.,[25][26] who worked for them[27] and later received a Howard N. Potts Medal for his contributions to engineering.

Prior to the establishment of the ASA scale[31] and similar to Weston film speed ratings another manufacturer of photo-electric exposure meters, General Electric, developed its own rating system of so-called General Electric film values (often abbreviated as G-E or GE) around 1937.

For some while, ASA grades were also printed on film boxes, and they saw life in the form of the APEX speed value Sv (without degree symbol) as well.

ASA PH2.5-1960 was revised as ANSI PH2.5-1979, without the logarithmic speeds, and later replaced by NAPM IT2.5–1986 of the National Association of Photographic Manufacturers, which represented the US adoption of the international standard ISO 6.

The standard for color negative film was introduced as ASA PH2.27-1965 and saw a string of revisions in 1971, 1976, 1979, and 1981, before it finally became ANSI IT2.27–1988 prior to its withdrawal.

[35][36] It was used in the former Soviet Union since October 1951,[citation needed] replacing Hurter & Driffield (H&D, Cyrillic: ХиД) numbers,[35] which had been used since 1928.

Determining speed for color negative film is similar in concept but more complex because it involves separate curves for blue, green, and red.

For example, a photographer may rate an ISO 400 film at EI 800 and then use push processing to obtain printable negatives in low-light conditions.

Another example occurs where a camera's shutter is miscalibrated and consistently overexposes or underexposes the film; similarly, a light meter may be inaccurate.

Fast films, used for photographing in low light or capturing high-speed motion, produce comparatively grainy images.

[74] Kodak and Fuji also marketed E6 films designed for pushing (hence the "P" prefix), such as Ektachrome P800/1600 and Fujichrome P1600, both with a base speed of ISO 400.

Some camera designs provide at least some EI choices by adjusting the sensor's signal gain in the digital realm ("expanded ISO").

A few camera designs also provide EI adjustment through a choice of lightness parameters for the interpretation of sensor data values into sRGB; this variation allows different tradeoffs between the range of highlights that can be captured and the amount of noise introduced into the shadow areas of the photo.

Faster microprocessors, as well as advances in software noise reduction techniques allow this type of processing to be executed the moment the photo is captured, allowing photographers to store images that have a higher level of refinement and would have been prohibitively time-consuming to process with earlier generations of digital camera hardware.

The Recommended Exposure Index (REI) technique, new in the 2006 version of the standard, allows the manufacturer to specify a camera model's EI choices arbitrarily.

The choices are based solely on the manufacturer's opinion of what EI values produce well-exposed sRGB images at the various sensor sensitivity settings.

The CIPA DC-004 standard requires that Japanese manufacturers of digital still cameras use either the REI or SOS techniques, and DC-008[78] updates the Exif specification to differentiate between these values.

The factor 78 is chosen such that exposure settings based on a standard light meter and an 18-percent reflective surface will result in an image with a grey level of 18%/√2 = 12.7% of saturation.

In all cases, the camera should indicate for the white balance setting for which the speed rating applies, such as daylight or tungsten (incandescent light).

Following the publication of CIPA DC-004 in 2006, Japanese manufacturers of digital still cameras are required to specify whether a sensitivity rating is REI or SOS.

APS- and 35 mm-sized digital image sensors, both CMOS and CCD based, do not produce significant noise until about ISO 1600.