I. A. Richards

Four years later, when the Faculty of English at Cambridge was formally established, he was awarded a permanent post as a university lecturer.

[5] Eventually tiring of academic life at Cambridge, in 1939 he accepted an offer to teach in the school of education at Harvard University.

In 1974, he returned to Cambridge, having retained his fellowship at Magdalene, and lived in Wentworth House in the grounds of the college until his death five years later.

Richards' travels, especially in China, effectively situated him as the advocate for an international program, such as Basic English.

As an instructor in English literature at Cambridge University, Richards tested the critical-thinking abilities of his pupils; he removed authorial and contextual information from thirteen poems and asked undergraduates to write interpretations, in order to ascertain the likely impediments to an adequate response to a literary text.

That experiment in the pedagogical approach—critical reading without contexts—demonstrated the variety and depth of the possible textual misreadings that might be committed, by university students and laymen alike.

To that end, effective critical work required a closer aesthetic interpretation of the literary text as an object.

To substantiate interpretive criticism, Richards provided theories of metaphor, value, and tone, of stock response, incipient action, and pseudo-statement; and of ambiguity.

To establish critical precision, Richards examined the psychological processes of writing and reading poetry.

By their usages, compiled from experience, people decide and determine meaning by "how words are used in a sentence", in spoken and written language.

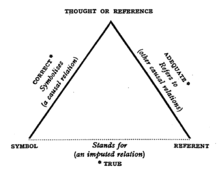

[11] Richards and Ogden created the semantic triangle to deliver an improved understanding of how words come to mean.

[13] The Oxford English Dictionary records that Richards coined the term feedforward in 1951 at the Eighth Macy Conferences on cybernetics.

Existing in all forms of communication,[14] feedforward acts as a pretest that any writer can use to anticipate the impact of their words on their audience.

They all admitted the value of his seminal ideas but sought to salvage what they considered his most useful assumptions from the theoretical excesses they felt he brought to bear in his criticism.