Ibn al-Nafis

[6][7][8] As an early anatomist, Ibn al-Nafis also performed several human dissections during the course of his work,[9] making several important discoveries in the fields of physiology and anatomy.

[14] Ibn al-Nafis was born between 1210 and 1213 to an Arab family[15] probably at a village near Damascus named Karashia, after which his Nisba might be derived.

He was contemporary with the famous Damascene physician Ibn Abi Usaibia and they both were taught by the founder of a medical school in Damascus, Al-Dakhwar.

Ibn al-Nafis was appointed as the chief physician at al-Naseri hospital which was founded by Saladin, where he taught and practiced medicine for several years.

Ibn al-Nafis lived most of his life in Egypt, and witnessed several pivotal events like the fall of Baghdad and the rise of Mamluks.

He even became the personal physician of the sultan Baibars and other prominent political leaders, thus showcasing himself as an authority among practitioners of medicine.

While it did not prove to be as popular as his medical encyclopedia in the Islamic circles, the book is of great interest today specially for science historians who are mostly concerned with its celebrated discovery of the pulmonary circulation.

It starts with a preface in which Ibn al-Nafis talks about the importance of the anatomical knowledge for the physician, and the vital relationship between anatomy and physiology.

What distinguish the book most is the confident language which Ibn al-Nafis shows throughout the text and his boldness to challenge the most established medical authorities of the time like Galen and Avicenna.

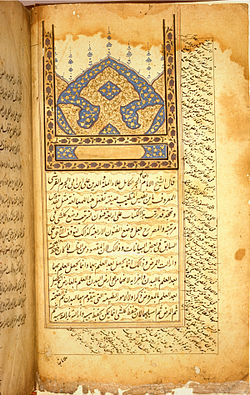

Based on evidence from commentaries such as this one, modern scholars know that physicians in this era received a license when they completed a particular part of their training.

[22] Ibn al-Nafis also wrote a number of books and commentaries on different topics including on medicine, law, logic, philosophy, theology, grammar and environment.

In 1924, Egyptian physician, Muhyo Al-Deen Altawi, discovered a manuscript entitled, Sharh tashrih al-qanun li’ Ibn Sina, or "Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon" in the Prussian State Library in Berlin while studying the history of Arabic Medicine at the medical faculty of Albert Ludwig's University.

Based on animal dissection, Galen hypothesized porosity in the septum in order for blood to travel within the heart as well as additional help on the part of the lungs.

“Ibn al-Nafīs's critiques were the result of two processes: an intensive theoretical study of medicine, physics, and theology in order to fully understand the nature of the living body and its soul; and an attempt to verify physiological claims through observation, including dissection of animals.”[27] Ibn al-Nafis rejected Galen's theory in the following passage:[27][28] The blood, after it has been refined in the right cavity, must be transmitted to the left cavity where the (vital) spirit is generated.

Instead, Ibn al-Nafis hypothesized that blood rose into the lungs via the arterial vein and then circulated into the left cavity of the heart.

The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa (pulmonary artery) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa (pulmonary vein) to reach the left chamber of the heart, and there form the vital spirit....[29][30]Elsewhere in this work, he said: The heart has only two ventricles...and between these two there is absolutely no opening.

He stated that "there must be small communications or pores (manafidh in Arabic) between the pulmonary artery and vein,"[32] a prediction that preceded the discovery of the capillary system by more than 400 years.

The venous artery, on the other hand, has thin substance in order to facilitate the reception of the transsuded [blood] from the vein in question.

And for the same reason there exists perceptible passages (or pores) between the two [blood vessels].Ibn al-Nafis also disagreed with Galen's theory that the heart's pulse is created by the arteries’ tunics.

He believed that "the pulse was a direct result of the heartbeat, even observing that the arteries contracted and expanded at different times depending upon their distance from the heart.

"[27] Ibn al-Nafis was also one of the few physicians at the time, who supported the view that the brain, rather than the heart, was the organ responsible for thinking and sensation.

Step one which he calls "the stage of presentation for clinical diagnosis" was to give the patient information on how it was to be performed and the knowledge it was based on.

The novel touches upon a variety of philosophical subjects like cosmology, empiricism, epistemology, experimentation, futurology, eschatology, and natural philosophy.

Ibn al-Nafis described his book Theologus Autodidactus as a defense of "the system of Islam and the Muslims' doctrines on the missions of Prophets, the religious laws, the resurrection of the body, and the transitoriness of the world."

He presents rational arguments for bodily resurrection and the immortality of the human soul, using both demonstrative reasoning and material from the hadith corpus to prove his case.

[46][47] In Alpago's 1547 A.D. publication of Libellus de removendis nocumentis, quae accident in regimime sanitatis, there is a Latin translation containing part of Ibn al-Nafis' commentary on pharmacopeia.

[48] Ibn al-Nafis’ mastery of medical sciences, his prolific writings, and also his image as a devout religious scholar left a positive impression on later Muslim biographers and historians, even among conservative ones like al-Dhahabi.

[50][51] George Sarton, in his "Introduction to the History of Science", written about the time Ibn al-Nafis's theory had just been discovered, said: If the authenticity of Ibn al-Nafis' theory is confirmed his importance will increase enormously; for he must then be considered one of the main forerunners of William Harvey and the greatest physiologist of the Middle Ages.

[52]In 2023, Egyptian publishing house "Dar Al-Sherouk" published "The Papermaker" or (in Arabic: الوراق)[53], a novel by Egyptian writer Youssef Zidane, the novel tell the real story of Ibn a-Nafis life, following The Crusades campaign against Damietta and northern Egypt, the Mongol invasion and the fall of Baghdad at the hands of Hulagu, the power struggles between the last generation of Ayyubids and the first generation of Mamluk rulers, the fierce clashes between Qutuz, Baybars and Qalawun... and "Al-Ala Ibn al-Nafis" between all that, who was close to all of that, as he was the personal physician of al-Zahir Baybars, and the chief physician of Egypt and the Levant.