Icelandic horse

In their native Iceland they have few afflictions or diseases, thus national laws are in place preventing foreign-born horses from being imported into the country, while exported animals are not permitted to return.

Centuries of selective breeding have developed the Icelandic horse into its modern physical form, with natural selection having also played a role in overall hardiness and disease resistance; the harsh Icelandic climate likely eliminated many weaker horses early on due to exposure and malnourishment, with the strongest passing on their genes.

[6][7] Another theory suggests that the breed's weight, bone structure, rideability and weight-carrying abilities mean it can be classified as a horse, rather than a pony.

[12] As a result of their isolation from other horses, diseases in the breed on the island of Iceland are virtually unknown, albeit with the exception of certain kinds of internal parasites.

The low prevalence of disease in Iceland is attributed to strict Icelandic law preventing horses which have been exported out of the country from being returned, and by requiring that all equine equipment brought into the country be either brand-new and unused, and/or fully disinfected.

Hence, Iceland-born horses have no acquired immunity to many diseases; an infection on the island would likely be devastating to the entire breed.

[3] These later settlers arrived with the ancestors of what would elsewhere become Shetland, Highland, and Connemara ponies, which were crossed with the previously imported animals.

[17] Other breeds with similar characteristics include the Faroe pony of the Faeroe Islands[18] and the Norwegian Fjord horse.

[20][21][22] Mongolian horses are believed to have been originally imported from Russia by Swedish traders; this imported Mongol stock subsequently contributed to the Fjord, Exmoor, Scottish Highland, Shetland and Connemara breeds, all of which have been found to be genetically linked to the Icelandic horse.

[23][24] The early Germanic peoples, including those living in Scandinavia, venerated horses and slaughtered and ate them at blóts throughout the Viking Age.

[3] Horses play a significant part in Nordic mythology with many, including Odin's eight-footed pacer named Sleipnir, allowing gods and other beings to travel between realms and across the sky.

According to the book, a chieftain named Seal-Thorir founded a settlement at the place where Skalm stopped and lay down with her pack.

[27] Indispensable to warriors, war horses were sometimes buried alongside their fallen riders,[12] and stories were told of their deeds.

Icelanders also arranged for bloody fights between stallions; these were used for entertainment and to pick the best animals for breeding, and they were described in both literature and official records from the Commonwealth period of 930 to 1262 AD.

[3] Stallion fights were an important part of Icelandic culture, and brawls, both physical and verbal, among the spectators were common.

However, not all human fights were serious, and the events provided a stage for friends and even enemies to battle without the possibility of major consequences.

[28] Natural selection played a major role in the development of the breed, as large numbers of horses died from lack of food and exposure to the elements.

Between 874 and 1300 AD, during the more favorable climatic conditions of the medieval warm period,[29] Icelandic breeders selectively bred horses according to special rules of color and conformation.

The eruption lasted eight months, covered hundreds of square miles of land with lava, and rerouted or dried up several rivers.

[2] Icelandics were exported to Great Britain before the 20th century to work as pit ponies in the coal mines, because of their strength and small size.

[27] Great Britain's first official imports were in 1956, when a Scottish farmer, Stuart McKintosh, began a breeding program.

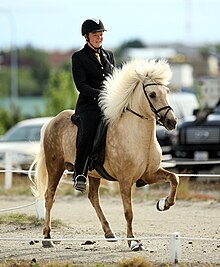

[12] The Agricultural Society of Iceland, along with the National Association of Riding Clubs, organizes regular shows with a wide variety of classes.

[2] Farmers still use the breed to round up sheep in the Icelandic highlands, and tourism is a growing industry, but most horses are used for competition and leisure riding.

[36] The FEIF was founded on 25 May 1969, with six countries as original members: Austria, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

[39] The registry contains information on the pedigree, breeder, owner, offspring, photo, breeding evaluations and assessments, and unique identification of each horse registered.