Icon

[6] Aside from the legend that Pilate had made an image of Christ, the 4th-century Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Church History, provides a more substantial reference to a "first" icon of Jesus.

Saint Irenaeus, (c. 130–202) in his Against Heresies (1:25;6) says scornfully of the Gnostic Carpocratians: They also possess images, some of them painted, and others formed from different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at that time when Jesus lived among them.

At the Spanish non-ecumenical Synod of Elvira (c. 305) bishops concluded, "Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and adoration".

have thought it to represent Aesculapius, the Greek god of healing, but the description of the standing figure and the woman kneeling in supplication precisely matches images found on coins depicting the bearded emperor Hadrian (r. 117–138) reaching out to a female figure—symbolizing a province—kneeling before him.

When asked by Constantia (Emperor Constantine's half-sister) for an image of Jesus, Eusebius denied the request, replying: "To depict purely the human form of Christ before its transformation, on the other hand, is to break the commandment of God and to fall into pagan error.

This recognition of a religious apparition from likeness to an image was also a characteristic of pagan pious accounts of appearances of gods to humans, and was a regular topos in hagiography.

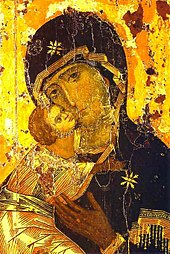

[19][20] This remained in the possession of the Angevin dynasty who had it inserted into a much larger image of Mary and the Christ child, which is presently enshrined above the high altar of the Benedictine Abbey church of Montevergine.

[21][20] This icon was subjected to repeated repainting over the subsequent centuries, so that it is difficult to determine what the original image of Mary's face would have looked like.

According to Reformed Baptist pastor John Carpenter, by claiming the existence of a portrait of the Theotokos painted during her lifetime by the evangelist Luke, the iconodules "fabricated evidence for the apostolic origins and divine approval of images.

Though by this time opposition to images was strongly entrenched in Judaism and Islam, attribution of the impetus toward an iconoclastic movement in Eastern Orthodoxy to Muslims or Jews "seems to have been highly exaggerated, both by contemporaries and by modern scholars".

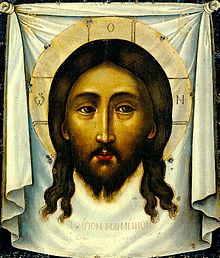

Like icons believed to be painted directly from the live subject, they therefore acted as important references for other images in the tradition.

As can be judged from such items, the first depictions of Jesus were generic, rather than portrait images, generally representing him as a beardless young man.

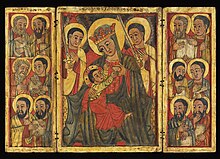

In icons of Jesus and Mary, Jesus wears red undergarment with a blue outer garment (representing God becoming human) and Mary wears a blue undergarment with a red overgarment (representing a human who was granted gifts by God), and thus the doctrine of deification is conveyed by icons.

This is because icon painting is rooted in the theology of the Incarnation (Christ being the eikon of God) which did not change, though its subsequent clarification within the Church occurred over the period of the first seven Ecumenical Councils.

[citation needed] Eastern Orthodox believe these qualify as icons, in that they were visible images depicting heavenly beings and, in the case of the cherubim, used to indirectly indicate God's presence above the Ark.

According to John of Damascus, anyone who tries to destroy icons "is the enemy of Christ, the Holy Mother of God and the saints, and is the defender of the Devil and his demons".

Les Bundy, "The Ecumenical Counciliar dogmatic decrees on icons refer, in fact, to all religious images including three-dimensional statues.

After 1453, the Byzantine tradition was carried on in regions previously influenced by its religion and culture—in the Balkans, Russia, and other Slavic countries, Georgia and Armenia in the Caucasus, and among Eastern Orthodox minorities in the Islamic world.

In the Greek-speaking world Crete, ruled by Venice until the mid-17th century, was an important centre of painted icons, as home of the Cretan School, exporting many to Europe.

For ease of transport, Cretan painters specialized in panel paintings, and developed the ability to work in many styles to fit the taste of various patrons.

El Greco, who moved to Venice after establishing his reputation in Crete, is the most famous artist of the school, who continued to use many Byzantine conventions in his works.

From that time Greek icon painting went into a decline, with a revival attempted in the 20th century by art reformers such as Photis Kontoglou, who emphasized a return to earlier styles.

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in 988 AD.

In the mid-17th century, changes in liturgy and practice instituted by Patriarch Nikon of Moscow resulted in a split in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Only in the 15th century did production of painted works of art begin to approach Eastern levels, supplemented by mass-produced imports from the Cretan School.

In this century, the use of icon-like portraits in the West was enormously increased by the introduction of old master prints on paper, mostly woodcuts which were produced in vast numbers (although hardly any survive).

Following Gregory the Great, Catholics emphasize the role of images as the Biblia Pauperum, the "Bible of the Poor", from which those who could not read could nonetheless learn.

Lutherans, however, rejected the iconoclasm of the 16th century, and affirmed the distinction between adoration due to the Triune God alone and all other forms of veneration (CA 21).

Yet, Lutherans and Orthodox are in agreement that the Second Council of Nicaea confirms the christological teaching of the earlier councils and in setting forth the role of images (icons) in the lives of the faithful reaffirms the reality of the incarnation of the eternal Word of God, when it states: "The more frequently, Christ, Mary, the mother of God, and the saints are seen, the more are those who see them drawn to remember and long for those who serve as models, and to pay these icons the tribute of salutation and respectful veneration.

Certainly this is not the full adoration in accordance with our faith, which is properly paid only to the divine nature, but it resembles that given to the figure of the honored and life-giving cross, and also to the holy books of the gospels and to other sacred objects" (Definition of the Second Council of Nicaea).