Idrimi

Idrimi would have succeeded in gaining the throne of Alalakh with the assistance of a group known as the Habiru,[6] founding the kingdom of Mukish as a vassal to the Mitanni state.

Jacob Lauinger considers Idrimi as a historical character, king of Alalakh around 1450 BC, in Late Bronze Age, but suggests his statue and inscriptions can be dated from c. 1400 to 1350 BC, and be related to a Mesopotamian pseudo-autobiography (called narû-literature), in which kings apparently leave records of their misadventures as a lesson for future generations.

Lauinger also comments that the inscriptions try to legitimate the rule of Alalakh only by acknowledging the supremacy of Mitanni, and the text(s) may have had an audience coeval to politics of that time.

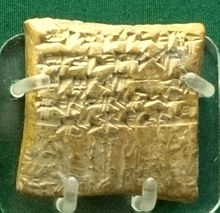

The inscription bears 104 lines "written in a provincial dialect of Akkadian,"[8] and records Idrimi's autobiographical vicissitudes on his statue's base found within a pit of a Level IB temple[9][10] at the site of Tell Atchana (Alalakh).

"[17] The second part of the inscription revealed major events in Idrimi's life including a campaign in Hurrian territory to reclaim Alalakh.

The inscription further stated: Idrimi built ships and likely gathered soldiers from Mukish, Amae, Nihi, and Alakah, which was enough to impress his own brothers to join him in reclaiming Alalakh.

Many scholars studying the inscription have suggested it to be a form of pseudo-history, possibly based on "exaggerations" of his campaigns,[5] or a moralizing story, composed 50-100 years after Idrimi's lifetime.

Jack M. Sasson of the University of North Carolina speculated that Idrimi didn't claim any relationship to Halab's rulers.

He argued that Ilim-Ilimma I, Idrimi's father, was either dethroned or had unsuccessfully attempted to usurp the throne of Halab from an unknown king.

According to Tremper Longman, lines 8b-9 of the autobiography indicate that Idrimi may have considered retaking his father's lost throne, and that he tried to involve his brothers in his cause.

Edward Greenstein and David Marcus' translation of the inscription on lines 29–34 revealed that following the storm-god Teshub's advice in a dream, Idrimi, and he adds that, This newfound alliance with local rulers, created by cattle exchanges, was just the beginning of the gradual restoration of Idrimi's royal status as the king of Alalakh.

He made his request to the throne peacefully by restoring Barattarna's estate and swore him an ultimate Hurrian loyalty oath, which was the first step to Idrimi regaining his power again.

Marc Van de Mieroop mentioned that Idrimi "captured" Alalakh implying a warfare approach that the inscription doesn't give.

He only allowed Idrimi limited independence of making his own military and diplomatic decisions just as long as it didn't interfere with Mitanni's overall policy.

[33] Lines 77-78 from Greenstein's and Marcus's translation of the statue inscription confirmed Collon's argument of what Idrimi did with his booty: The inscription from lines 78-86 of that same translation states, It is possible according to the statue text that Idrimi would have used his "spoils of war" from the seven Hittite towns, especially any valuable items, to help fund the rebuilding of his cities.

Jack M. Sasson of the University of North Carolina contended that Sharruwa wrote the inscription for selfish reasons to bolster his national pride.

Dominique Collon refuted his arguments by saying that many of the documents associated with Idrimi in the Level 4 Alalakh palace archives discovered by Woolley were associated with his reign in 1490–1460 BC, therefore giving some validity to Sharruwa's statements.

His seal represented his act of piety towards the Shutu people and to those who "had no settled abode," to show his generosity as a king and former Habiru refugee as he rebuilt his cities.

[38] Royal seals were frequently used in the Hittite Empire and Hurrian regions in northern Syria to demonstrate the king's power in Idrimi's time.

The failence was heated at a lower temperature so that the surface could have a glazed appearance, allowing them to be easily carved and cheaply produced.