Legitimacy (family law)

"[3] Under English law, a bastard could not inherit real property and could not be legitimized by the subsequent marriage of father to mother.

[12] Still, children born out of wedlock may not be eligible for certain federal benefits (e.g., automatic naturalization when the father becomes a US citizen) unless the child has been legitimized in the appropriate jurisdiction.

Countries which ratify it must ensure that children born outside marriage are provided with legal rights as stipulated in the text of this convention.

[23] More recently, the laws of England have been changed to allow illegitimate children to inherit entailed property, over their legitimate brothers and sisters.

[citation needed] Despite the decreasing legal relevance of illegitimacy, an important exception may be found in the nationality laws of many countries, which do not apply jus sanguinis (nationality by citizenship of a parent) to children born out of wedlock, particularly in cases where the child's connection to the country lies only through the father.

[25] In the UK, the policy was changed so that children born after 1 July 2006 could receive British citizenship from their father if their parents were unmarried at the time of the child's birth; illegitimate children born before this date cannot receive British citizenship through their father.

For example, Elizabeth I succeeded to the throne though she was legally held illegitimate as a result of her parents' marriage having been annulled after her birth.

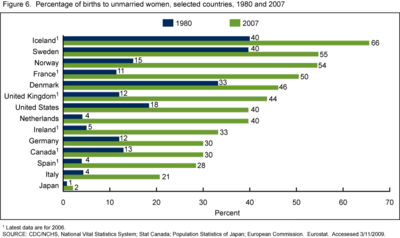

The proportion of children born outside marriage has been rising since the turn of the 21st century in most European Union countries,[49][50] North America, and Australia.

[61] One of the reasons for the lower prevalence of non-marital births in the metropolis is the high number of immigrants from conservative world regions.

[64] Traditionally conservative Catholic countries in the EU now also have substantial proportions of non-marital births, as of 2016 (except where otherwise stated):[56] Portugal (52.8% [65]), Spain (45.9%), Austria (41.7%[66]), Luxembourg (40.7%[56]) Slovakia (40.2%[67]), Ireland (36.5%),[68] Malta (31.8%[67]) The percentage of first-born children born out of wedlock is considerably higher (by roughly 10%, for the EU), as marriage often takes place after the first baby has arrived.

Frequencies as high as 30% are sometimes assumed in the media, but research[79][80] by sociologist Michael Gilding traced these overestimates back to an informal remark at a 1972 conference.

[88][89][90] Before the dissolution of Marxist–Leninist regimes in Europe, women's participation in the workforce was actively encouraged by most governments, but socially conservative regimes such as that of Nicolae Ceausescu practiced restrictive and natalist policies regarding family reproduction, such as total bans on contraception and abortion, and birth rates were tightly controlled by the state.

[58] Far-right regimes such as those of Francoist Spain and Portugal's Estado Novo also fell, leading to the democratization and liberalization of society.

This [indicates] clear changes in [people's] value orientations [...] and less social pressure for marriage.Certainty of paternity has been considered important in a wide range of eras and cultures, especially when inheritance and citizenship were at stake, making the tracking of a man's estate and genealogy a central part of what defined a "legitimate" birth.

The ancient Latin dictum, "Mater semper certa est" ("The [identity of the] mother is always certain", while the father is not), emphasized the dilemma.

In other cases nonmarital children have been reared by grandparents or married relatives as the "sisters", "brothers" or "cousins" of the unwed mothers.

Fathers of illegitimate children often did not incur comparable censure or legal responsibility, due to social attitudes about sex, the nature of sexual reproduction, and the difficulty of determining paternity with certainty.

In the early 1970s, a series of Supreme Court decisions abolished most, if not all, of the common-law disabilities of non-marital birth, as being violations of the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Before this, the mother and father of many children had been unable to marry each other because one or the other was already legally bound, by civil or canon law, in a non-viable earlier marriage that did not permit divorce.

[102][103] Some persons born outside of marriage have been driven to excel in their endeavors, for good or ill, by a desire to overcome the social stigma and disadvantage that attached to it.

Nora Titone, in her book My Thoughts Be Bloody, recounts how the shame and ambition of actor Junius Brutus Booth's two actor sons born outside of marriage, Edwin Booth and John Wilkes Booth, spurred them to strive, as rivals, for achievement and acclaim—John Wilkes, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, and Edwin, a Unionist who a year earlier had saved the life of Lincoln's son, Robert Todd Lincoln, in a railroad accident.

[105] The Swedish artist Anders Zorn (1860–1920) was similarly motivated by his non-marital birth to prove himself and excel in his métier.

"[97] Another biographer, John E. Mack, writes in a similar vein: "[H]is mother required of him that he redeem her fallen state by his own special achievements, by being a person of unusual value who accomplishes great deeds, preferably religious and ideally on an heroic scale.

Lawrence's capacity for invention and his ability to see unusual or humorous relationships in familiar situations come also... from his illegitimacy.

He was not limited to established or 'legitimate' solutions or ways of doing things, and thus his mind was open to a wider range of possibilities and opportunities.

[112] In more recent times, Steve Jobs' adoption due to the nonmarried status of his biological parents influenced his life and career.

Women who have given birth under such circumstances are often subjected to violence at the hands of their families; and may even become victims of so-called honor killings.

[115][116][117] These women may also be prosecuted under laws forbidding sexual relations outside marriage and may face consequent punishments, including stoning.

[118] Illegitimacy has for centuries provided a motif and plot element to works of fiction by prominent authors, including William Shakespeare, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Fielding, Voltaire, Jane Austen, Alexandre Dumas, père, Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Wilkie Collins, Anthony Trollope, Alexandre Dumas, fils, George Eliot, Victor Hugo, Leo Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Thomas Hardy, Alphonse Daudet, Bolesław Prus, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, E. M. Forster, C. S. Forester, Marcel Pagnol, Grace Metalious, John Irving, and George R. R. Martin.

Some pre-20th-century modern individuals whose unconventional "illegitimate" origins did not prevent them from making (and in some cases helped inspire them to make) notable contributions to humanity's art or learning have included Leone Battista Alberti[119] (1404–1472), Leonardo da Vinci[120] (1452–1519), Erasmus of Rotterdam[121] 1466–1536), Jean le Rond d'Alembert[122] (1717–1783), Alexander Hamilton (1755 or 1757–1804), James Smithson[123] (1764–1829), John James Audubon[124] (1785–1851), Alexander Herzen[125] (1812–1870), Jenny Lind[126] (1820–1887), and Alexandre Dumas, fils[127] (1824–1895).