Immigration to Japan

Due to geographic remoteness and periods of self-imposed isolation, the immigration, cultural assimilation and integration of foreign nationals into mainstream Japanese society has been comparatively limited.

The demands of small business owners and demographic shifts in the late 1980s, however, gave rise for a limited period to a wave of tacitly accepted illegal immigration from countries as diverse as the Philippines and Iran.

[3] Production offshoring in the 1980s also enabled Japanese firms in some labor-intensive industries such as electronic goods manufacture and vehicle assembly to reduce their dependence on imported labor.

In 2009, with economic conditions less favorable, this trend was reversed as the Japanese government introduced a new program that would incentivize Brazilian and Peruvian immigrants to return home with a stipend of $3000 for airfare and $2000 for each dependent.

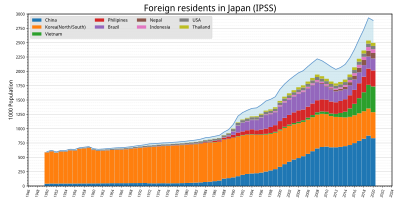

[5] The years 2022–23 have seen rising immigration after policy changes seemingly in reaction to labour shortages, particularly in retail and hospitality industries.

The granting of permanent residence status is at the discretion of the Immigration Bureau and dependent on satisfaction of a number of detailed criteria such as length of stay, ability to make an independent living, record of tax payments and documented contributions to Japan in terms of public service or professional activities.

The country therefore has made a commitment to offer protection to people who seek asylum and fall into the legal definition of a refugee, and moreover, not to return any displaced person to places where they would otherwise face persecution.

[34] Between 2010 and January 2018, a rise in the number of asylum seekers in Japan was attributed in part to a legal loophole related to the government administered Technical Intern Training Program.

[27] In 2015, 192,655 vocational trainees mainly from developing economies were working in Japan in factories, construction sites, farms, food processing and in retail.

Permits enabling legal employment six months after application for refugee status were discontinued by the Justice Ministry in January 2018.

Workplace inspections and illegal immigration deportation enforcement activities were subsequently stepped up aimed at curbing alleged abuse of the refugee application system.

[39] Illegal immigrant numbers had peaked at approximately 300,000 in May 1993,[citation needed] but have been gradually reduced through a combination of stricter enforcement of border controls, workplace monitoring and an expansion of government-run foreign worker programs for those seeking a legal route to short term employment opportunities in Japan.

Border controls at ports of entry for foreign nationals include examination of personal identification documentation, finger printing and photo recording.

Historically the bulk of those taking Japanese citizenship have not been new immigrants but rather Special Permanent Residents; Japan-born descendants of Koreans and Taiwanese who remained in Japan at the end of the Second World War.

[48] In 2005, future Prime Minister Tarō Asō described Japan as being a nation of "one race, one civilization, one language and one culture"[49] and in 2012, this claim was repeated by former Governor of Tokyo Shintaro Ishihara.

[citation needed] In 1993, 64% of respondents supported allowing firms facing labor shortages to hire unskilled foreign workers.

[51] A 2017 poll by Gallup shows a similar attitude 24 years later, with Japan middling among developed countries in terms of public positivity towards immigration, ranking close to France, Belgium and Italy.

[57] However, a large poll of 10,000 native Japanese conducted later that year, between October and December 2015, found more opposition to increasing foreign immigration.

[59] On the other hand, one of the common arguments for restricting immigration is based on safeguarding security, including public order, protecting welfare mechanisms, cultural stability, or social trust.