History of Cologne

The city became an influential merchant stronghold in the early Middle Ages due to its location on the Rhine, which allowed the most seasoned Cologne wholesalers to control the flow of goods from northern Italy to England.

[2] In the following centuries, dynamic growth of Cologne was driven by enhanced merchant activities on river Rhine; in addition, the town became seat of an influential archbishop.

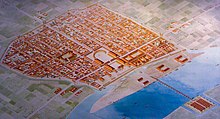

[12] In 39 BC the Germanic tribe of the Ubii entered into an agreement with the forces of the Roman General Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and settled on the left bank of the Rhine.

In 50 AD the Cologne-born Agrippina the Younger, wife of the Emperor Claudius, asked for her home village to be raised to the status of a colonia — a city under Roman law.

Ten years later, the colonia became the capital of the Roman province of Lower Germany, Germania Inferior, with a total population of 45,000 people[citation needed][dubious – discuss] occupying 96.8 hectares.

Cologne passed to East Francia but was soon reconquered by Henry the Fowler, deciding its fate as a city of the Holy Roman Empire (and eventually Germany) rather than France.

Since the archbishop refrained to abide by the financial agreements he had entered into when elected in 1463, the cathedral chapter appointed Landgrave Hermann IV of Hesse as diocesan administrator in 1473.

Perceived as insubordination, the archbishop in consequence asked for military assistance from the powerful Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, ruler of Flanders and Dutch regions.

Within months, the citizenry succeeded in persuading Emperor Friedrich III to intervene with an imperial army; their arrival before Neuss forced the Burgundian troops to withdraw from the siege.

[23] Overall, Cologne prospered as merchant city until the middle of the 16th century, which continued to control the flow of goods across the Rhine from London to Italy and at the same time linked them with west-east trade routes to Frankfurt and Leipzig.

As an indirect result of the Cologne Diocesan Feud, in 1477 heir Maximilian of Austria had married Maria, Duchess of Burgundy, thus enabling Habsburg access to the rich Burgundian lands of Flanders and the Netherlands.

The council, dominated by these circles, tried to maintain the city's solvency by raising indirect taxes – especially on food and wine – in order to assure the debt service.

[30] In 1481, councilor Werner von Lyskirchen, who was descended from one of Cologne's old patrician families, used the latent discontent in cooperative circles (Gaffeln) and guilds to attempt a coup.

[31] In the course of a dispute in 1512, the small circles in the council were tempted to bend the law and commit fraud in order to defend their privileges, at least from the point of view of rival citizens.

[32] New rules of conduct, intended to contain the re-emergence of oligarchic structures, were codified by December 1513 in an amendment letter (Transfixbrief), which supplemented the city constitution (Verbundbrief) in force since 1396.

The most sophisticated mastery of Cologne late Gothic sculpture is realized in the rood screen of St. Pantaleon Church, attributed to Master Tilman, and donated by Abbot Johannes Lüninck around 1502.

[52] In 1524, Quentel published an edition in Low German language of Luther’s New Testament translation; from the late 1520s, however, the printing and distribution of Lutheran books was banned by the Cologne Council.

[53] By developing into a leading publishing place for Latin-language works Cologne gained an exceptional position compared to all other book printing centers of the empire.

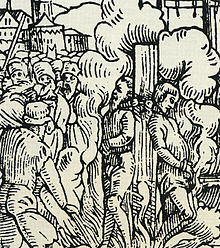

The driver of this anti-Jewish action was Johannes Pfefferkorn, a Jew convert to Catholic Christianity who was apparently supported by the Cologne Dominican Order;[56] the Dominican theologian Jacob van Hoogstraaten, prior to the convent of Cologne, and acting as a papal inquisitor, flanked the anti-Jewish religious propaganda with expert opinions and prohibitory pamphlets, which were mainly directed against Johannes Reuchlin, a leading humanist and Hebraist.

[69] The town hall’s extension, called Löwenhof (Lion‘s Courtyard), was built in 1540 by Laurenz Cronenberg blending elements in late Gothic and Renaissance style.

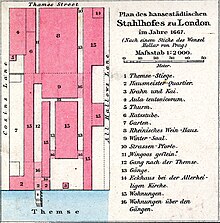

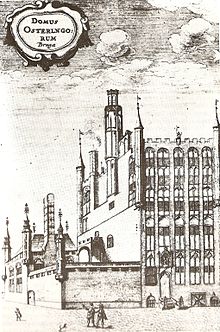

[76] In order to strengthen its traditional business branches – especially wine and cloth – Cologne became intensively involved in the Hanseatic League and in 1556 created the role of a syndic, a kind of secretary-general in an institution that until then had not known any representative.

Because of the tensions, many refugees left Antwerp and settled in Cologne; among the most illustrious were Jan Rubens, father of the subsequently famous painter Peter Paul, and Anna of Saxony, wife of William of Orange, who eventually became governor of the united Dutch provinces.

[86] The cartographer Arnold Mercator drew up the plan at a scale of 1:2450, striving for a work that satisfied cartographic-scientific standards; the map was based on a comparatively accurate survey of the city's topography and showed the building tracts in the aim to create a spatial effect with a skillful mixture of elevation and bird's-eye view.

To pacify the disputes in the provinces, which formally still were part of the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Rudolf II, the brother-in-law of the Spanish king, sought a negotiated settlement.

The so-called Pacification Day took place in Cologne from April to November 1579, because the imperial city, as a strategically important metropolis, could be accepted as a neutral location and provide the necessary infrastructure for the delegations.

As powerful electors, the archbishops repeatedly challenged Cologne's free status during the 17th and 18th centuries, resulting in complicated legal affairs, which were handled by diplomatic means, usually to the advantage of the city.

Konrad Adenauer, mayor of Cologne from 1917 until 1933 and a future West German chancellor, acknowledged the political impact of this approach, especially that the British opposed French plans for a permanent Allied occupation of the Rhineland.

The trade fair grounds next to the Deutz train station were used to herd the Jewish population together for deportation to the death camps and for disposal of their household goods by public sale.

The destruction of the famous twelve Romanesque churches, including St. Gereon's Basilica, Great St. Martin, St. Maria im Kapitol and about a dozen others during World War II, meant a tremendous loss of cultural substance to the city.

The rebuilding of these churches and other landmarks like the Gürzenich was not undisputed among leading architects and art historians at that time, but in most cases, civil intention[clarification needed] prevailed.

Cologne Cathedral