Import substitution industrialization

The term primarily refers to 20th-century development economics policies, but it has been advocated since the 18th century by economists such as Friedrich List[2] and Alexander Hamilton.

[10]: 164–165 In contrast to ISI policies, the Four Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) have been characterized as government intervention to facilitate "export-oriented industrialization".

Import substitution was heavily practiced during the mid-20th century as a form of developmental theory that advocated increased productivity and economic gains within a country.

Mass poverty is defined as "the dominance of agricultural and mineral activities – in the low-income countries, and in their inability, because of their structure, to profit from international trade.

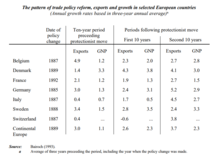

[15] Going further, in his book Kicking Away the Ladder, the South Korean economist Ha-Joon Chang also argues based on economic history that all major developed countries, including the United Kingdom, used interventionist economic policies to promote industrialization and protected national companies until they had reached a level of development in which they were able to compete in the global market.

The first steps in import substitution were less theoretical and more pragmatic choices on how to face the limitations imposed by recession even though the governments in Argentina (Juan Domingo Perón) and Brazil (Getúlio Vargas) had the precedent of Fascist Italy (and, to some extent, the Soviet Union) as inspirations of state-induced industrialization.

The officials, many of whom rose to power, like Perón and Vargas, considered industrialization (especially steel production) to be synonymous with "progress" and naturally placed as a priority.

[19] Prebisch came to the conclusion that the participants in the free-trade regime had unequal power and that the central economies (particularly, Britain and the United States) that manufactured industrial goods could control the price of their exports.

[21] To overcome the difficulties of implementing ISI in small-scale economies, proponents of the economic policy, some within UNECLAC, suggested two alternatives to enlarge consumer markets: income redistribution within each country by agrarian reform and other initiatives aimed at bringing Latin America's enormous marginalized population into the consumer market and regional integration by initiatives such as the Latin American Free Trade Association (ALALC), which would allow for the products of one country to be sold in another.

Against most opinions, one historian argued that ISI was successful in fostering a great deal of social and economic development in Latin America: "By the early 1960s, domestic industry supplied 95% of Mexico's and 98% of Brazil's consumer goods.

[23]: 124 Early attempts at ISI were stifled by colonial neomercantilist policies of the 1940s and the 1950s that aimed to generate growth by exporting primary products to the detriment of imports.

The metropolitan governments aimed to offset colonial expenditures and attain primary commercial products from Africa at a significantly reduced rate.

[24]: 206–215 That was successful for British commercial interests in Ghana and Nigeria, which increased 20 times the value of foreign trade between 1897 and 1960 because of the promotion of export crops such as cocoa and palm oil.

Marxist historians such as Walter Rodney contend that the gross underdevelopment in social services were a direct result of colonial economic strategy, which had to be abandoned to generate sustainable development.

The culmination of the political and economic issues necessitated the adoption of ISI, as it rejected the colonial neo-mercantilist policies that they believed had led to underdevelopment.

To achieve that, some newly independent states pursued African socialism to build indigenous growth and break free from capitalist development patterns.

[35] In line with that economic vision, Tanzania engaged in the nationalization of industry to create jobs and to produce a domestic market for goods while it maintained an adherence to African socialist principles exemplified through the ujamaa program of villagization.

Tom Mboya, the first minister for economic development and planning, aimed to create a growth-oriented path of industrialization, even at the expense of traditional socialist morals.

Economic historians such as Ralph Austen argue that the openness to western enterprise and technical expertise led to a higher GNP in Kenya than comparative socialist countries such as Ghana and Tanzania.

[40] In all of the countries that adopted ISI, the state oversaw and managed its implementation, designing economic policies that directed development towards the indigenous population, with the aim of creating an industrialised economy.

The 1972 Nigerian Enterprises Promotion Decree exemplified such control, as it required foreign companies to offer at least 40% of their equity shares to local people.

[41] That correlates with the theory of neo-patrimonialism, which claims that post-colonial elites used the coercive powers of the state to maintain their political positions and to increase their personal wealth.

[42] Ola Olson opposes that view by arguing that in a developing economy, the government is the only actor with the financial and political means to unify the state apparatus behind an industrialization process.

[45] A 1982 World Bank report stated, "There exists a chronic shortage of skills which pervades not only the small manufacturing sector but the entire economy and the over-loaded government machine.

Learning and adopting the technological resources and skills was a protracted and costly process, something that African states were unable to capitalise on because of the lack of domestic savings and poor literacy rates across the continent.

In response to the underdeveloped economies in the region, the IMF and the World Bank imposed a neo-classical counter-revolution in Africa through Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) from 1981.

[47] For the IMF and the World Bank, the solution to the failure of import substitution was a restructuring of the economy towards strict adherence to a neoliberal model of development throughout the 1980s and the 1990s.

The theory of comparative advantage shows how countries within the model gain from trade, however, this concept has received criticism for its misguided underlying assumptions and inapplicability to modern production.