In situ

Biological field research examines organisms in their natural habitats, revealing behavioral patterns and ecological interactions that laboratory settings cannot replicate.

In chemistry and experimental physics, in situ techniques enable the observation of substances and reactions under native conditions, facilitating the documentation of dynamic processes.

Space exploration utilizes in situ planetary research methods, conducting direct observational studies and data collection on celestial bodies, thereby avoiding the complexities inherent in sample-return missions.

Archaeological investigations preserve the spatial relationships and environmental conditions of artifacts at excavation sites, enabling more precise historical analysis.

This contextual placement establishes a methodological framework that emphasizes the relationship between artistic works and their environmental or cultural settings.

In aerospace structural health monitoring, in situ inspection denotes diagnostic methodologies that evaluate components within their operational environments—eliminating the need for disassembly or service interruption.

The nondestructive testing (NDT) techniques employed for in situ damage detection include: infrared thermography, which measures thermal emissions to identify structural anomalies; speckle shearing interferometry (also known as shearography), which analyzes surface deformation patterns; and ultrasonic testing, which uses sound wave propagation to detect internal defects in composite materials.

Infrared thermography exhibits reduced effectiveness on low-emissivity materials,[5] shearography requires carefully controlled environmental conditions,[6] and ultrasonic testing protocols can be time-intensive for large structural components.

[4] An additional approach involves the use of alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) sensor arrays in real-time monitoring applications, facilitating in situ detection of structural degradation phenomena—including matrix discontinuities, interlaminar delaminations, and fiber fracture mechanisms—through quantitative analysis of electrical resistance and capacitance variations within composite laminate configurations.

The systematic documentation of spatial coordinates, stratigraphic position, and associated matrices of in situ materials enables the reconstruction of historical processes and cultural practices.

While artifacts frequently require extraction for analytical purposes, archaeological features—including hearths, postholes, and architectural foundations—necessitate comprehensive in situ documentation to preserve contextual data during stratigraphic excavation.

Contemporary archaeological practice incorporates advanced digital technologies, including 3D laser scanning, photogrammetry, unmanned aerial vehicles, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), to capture complex spatial relationships.

[9] Materials recovered from secondary contexts (ex situ), including those displaced through non-professional excavation activities, demonstrate diminished interpretive value; however, such assemblages may provide diagnostic indicators regarding the spatial distribution and typological characteristics of unexcavated in situ deposits, thereby informing subsequent excavation plans.

The extraction of artifacts from these submerged environments and subsequent exposure to atmospheric conditions typically accelerates deterioration processes, most notably in the oxidation of ferrous materials.

[12]: 5 In archaeological contexts involving burial sites, in situ documentation encompasses the systematic recording and cataloging of human remains in their original depositional positions, often within complex matrices that incorporate sediments, clothing, and other associated artifacts.

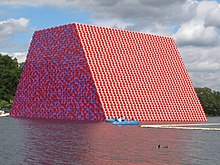

[13] The concept of in situ in contemporary art emerged as a critical framework during the late 1960s and 1970s, designating artworks conceived and executed for specific spatial contexts.

[14]: 160–162 This methodology stands in contrast to autonomous artistic production, wherein works maintain independence from their eventual display locations.

The approach to in situ practice underwent further development through the land art movement, wherein practitioners such as Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer integrated their works directly into terrestrial environments, forging inextricable relationships between artistic intervention and geographical context.

[15] Within contemporary aesthetic discourse, the term in situ has evolved into a theoretical construct, denoting artistic methodologies predicated on the essential unity of work and site.

In biology and biomedical engineering, in situ means to examine the phenomenon exactly in place where it occurs (i.e., without moving it to some special medium).

For instance, an example of biomedical engineering in situ involves the procedures to directly create an implant from a patient's own tissue within the confines of the Operating Room.

It has tremendous applications for cancer treatment, vaccination, diagnosis, regenerative medicine, and therapies for loss-of-function genetic diseases.

The differences in the soil properties for supporting building loads, accepting underground utilities, and infiltrating water persist indefinitely.

A use of the term in-situ that appears in Computer Science focuses primarily on the use of technology and user interfaces to provide continuous access to situationally relevant information in various locations and contexts.

[20][21] Examples include athletes viewing biometric data on smartwatches to improve their performance,[22] a presenter looking at tips on a smart glass to reduce their speaking rate during a speech,[23] or technicians receiving online and stepwise instructions for repairing an engine.

[citation needed] In physical geography and the Earth sciences, in situ typically describes natural material or processes prior to transport.

External stimuli in in situ TEM/STEM experiments include mechanical loading and pressure, temperature changes, electrical currents (biasing), radiation, and environmental factors—such as exposure to gas, liquid, and magnetic field—or any combination of these.

[30][31] CIS is a critical term in early cancer diagnosis, as it signifies a non-invasive stage, allowing for more targeted interventions before potential progression.

[34] In situ refers to recovery techniques which apply heat or solvents to heavy crude oil or bitumen reservoirs beneath the Earth's crust.

The most common type of in situ petroleum production is referred to as SAGD (steam-assisted gravity drainage) this is becoming very popular in the Alberta Oil Sands.