In situ

By contrast, ex situ methods involve the removal or displacement of materials, specimens, or processes for study, preservation, or modification in a controlled setting, often at the cost of contextual integrity.

In chemistry and experimental physics, in situ techniques allow scientists to observe substances and reactions as they occur, capturing dynamic processes in real time.

Space exploration relies on in situ research methods to conduct direct observational studies and data collection on celestial bodies, eliminating the challenges of sample-return missions.

[1] The usage of the term in scientific literature expanded steadily from the late 19th century onward, initially in medicine and engineering, including geological surveys and petroleum extraction.

For observations or photographs of living animals, in situ indicates that the organism was documented in its natural environment, without being relocated to another setting, such as an aquarium or laboratory.

For instance, an example of biomedical engineering in situ involves the procedures to directly create an implant from a patient's own tissue within the confines of the Operating Room.

In aerospace structural health monitoring, in situ inspection involves diagnostic techniques that assess components within their operational environments, eliminating the need for disassembly or service interruptions.

The nondestructive testing (NDT) methods commonly used for in situ damage detection include infrared thermography, which measures thermal emissions to identify structural anomalies but is less effective on low-emissivity materials;[10] speckle shearing interferometry (shearography), which analyzes surface deformation patterns but requires carefully controlled environmental conditions;[11] and ultrasonic testing, which uses sound waves to detect internal defects in composite materials but can be time-intensive for large structures.

Differences in soil properties affect structural support, underground utilities, and water infiltration, with implications for long-term site stability.

In computer science, in situ refers to the use of technology and user interfaces to provide continuous access to situationally relevant information across different locations and contexts.

[16][17] Examples include athletes viewing biometric data on smartwatches to improve their performance,[18] a presenter looking at tips on a smart glass to reduce their speaking rate during a speech,[19] or technicians receiving online and stepwise instructions for repairing an engine.

More broadly, asynchronous data transfers and background tasks can be considered in situ, as they operate without disrupting the primary user interface and typically notify completion through a callback mechanism.

An example is weathering, whereby rocks undergo physical or chemical disintegration in situ,[22] as opposed to erosion, which entails the removal and relocation of materials by agents such as wind, water, or ice.

These measurements provide real-time data about environmental conditions, offering insights into natural processes that remote methods cannot fully replicate.

Satellite remote sensing is used for mapping and monitoring forest health on a large scale, for example, by capturing spatial and temporal patterns; however, its accuracy depends on in situ verification, which is often inconsistent.

These measurements are typically obtained through shipboard surveys using instruments such as a CTD device, which records parameters such as salinity, temperature, pressure, and biogeochemical properties like oxygen saturation.

Historically, oceanographers used reversing thermometers to measure temperature at specific depths, while Niskin or Nansen bottles were employed to collect water samples for further physical, chemical, and biological analysis.

[4]: 1534 In situ, for example, describes the study of a sample maintained in a steady-state[b] condition within a controlled environment, where specific parameters such as temperature or pressure are regulated.

Examples include a sample held at a fixed temperature inside a cryostat, an electrode material operating within an electric battery, or a specimen enclosed within a sealed container to protect it from external influences.

External stimuli in in situ TEM/STEM experiments include mechanical loading and pressure, temperature changes, electrical currents (biasing), radiation, and environmental factors—such as exposure to gas, liquid, and magnetic field—or any combination of these.

[6][28] CIS is a critical term in early cancer diagnosis, as it signifies a non-invasive stage, allowing for more targeted interventions before potential progression.

[31] In archaeology, the term in situ refers to artifacts and other materials that remain in their original depositional context, undisturbed since their initial placement.

Recording the exact spatial coordinates, stratigraphic position, and surrounding matrix of in situ materials is crucial for reconstructing past human activities and historical processes.

Current archaeological practice incorporates advanced digital technologies, including 3D laser scanning, photogrammetry, unmanned aerial vehicles, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), to capture complex spatial relationships.

However, these displaced materials can still provide clues about the spatial distribution and typological characteristics of unexcavated in situ deposits, guiding future excavation efforts.

[32]: 558 [36]: 13 This policy is based on the unique conditions of underwater environments, where low oxygen levels and stable temperatures help preserve artifacts over long periods.

Before identifying individuals or determining causes of death, archaeologists must carefully document spatial relationships and contextual details to preserve forensic and historical information.

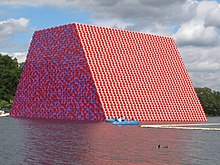

[38] In contemporary aesthetic discourse, in situ has expanded into a broader theoretical construct, describing artistic practices that reinforce the fundamental unity between a work and its site.

[41] In situ refers to recovery techniques which apply heat or solvents to heavy crude oil or bitumen reservoirs beneath the Earth's crust.

The most common type of in situ petroleum production is referred to as SAGD (steam-assisted gravity drainage) this is becoming very popular in the Alberta Oil Sands.