Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The refinement of moveable type and the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg c. 1440 changed the nature of book publishing, and the mechanism by which information could be disseminated to the public.

In the 16th century, both the churches and governments in most European countries attempted to regulate and control printing because it allowed for the rapid and widespread circulation of ideas and information.

The 1551 Edict of Châteaubriant comprehensively summarized censorship positions to date, and included provisions for unpacking and inspecting all books brought into France.

Historian Eckhard Höffner claims that copyright laws and their restrictions acted as a barrier to progress in those countries for over a century, since British publishers could print valuable knowledge in limited quantities for the sake of profit.

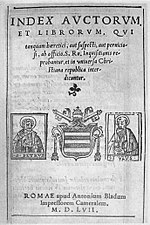

[21][22][page needed] The first list of the kind was not published in Rome, but in Catholic Netherlands (1529); Venice (1543) and Paris (1551) under the terms of the Edict of Châteaubriant followed this example.

Both church and government held to a belief in censorship, but the publishers continually pushed back on the efforts to ban books and shut down printing.

[note 2] Among the inclusions was the Libri Carolini, a theological work from the 9th-century court of Charlemagne, which was published in 1549 by Bishop Jean du Tillet and which had already been on two other lists of prohibited books before being inserted into the Tridentine Index.

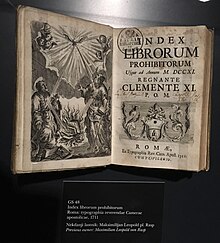

[29] Subsequent editions of the Index were more sophisticated; they graded authors according to their supposed degree of toxicity, and they marked specific passages for expurgation rather than condemning entire books.

The Congregation of the Index was merged with the Holy Office in 1917, by the motu proprio Alloquentes Proxime of Pope Benedict XV; the rules on the reading of books were again re-elaborated in the new Codex Iuris Canonici.

[34] Among the denounced works of the period was the Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, and the fundamentals of the Christian religion".

After gaining access to the Vatican Apostolic Archive church historian Hubert Wolf discovered that Mein Kampf had been studied for three years but the Holy Office decided that it should not go on the Index because the author was a head of state.

[31] On 7 December 1965, Pope Paul VI issued the motu proprio Integrae servandae that reorganized the Holy Office as the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

[39] Members of religious institutes require the imprimi potest ('it can be printed') of their major superior to publish books on matters of religion or morals.

[42] Spain had its own Index Librorum Prohibitorum et Expurgatorum, which corresponded largely to the Church's,[43] but also included a list of books that were allowed once the forbidden part (sometimes a single sentence) was removed or "expurgated".

[44] On 14 June 1966, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith responded to inquiries it had received regarding the continued moral obligation concerning books that had been listed in the Index.

In a letter of 31 January 1985 to Cardinal Giuseppe Siri, regarding the book The Poem of the Man-God, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (then Prefect of the Congregation, who later became Pope Benedict XVI), referred to the 1966 notification of the Congregation as follows: "After the dissolution of the Index, when some people thought the printing and distribution of the work was permitted, people were reminded again in L'Osservatore Romano (15 June 1966) that, as was published in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis (1966), the Index retains its moral force despite its dissolution.

A decision against distributing and recommending a work, which has not been condemned lightly, may be reversed, but only after profound changes that neutralize the harm which such a publication could bring forth among the ordinary faithful.

Writings by Antonio Rosmini-Serbati were placed on the Index in 1849 but were removed by 1855, and Pope John Paul II mentioned Rosmini's work as a significant example of "a process of philosophical enquiry which was enriched by engaging the data of faith".

[50] Noteworthy figures on the Index include Simone de Beauvoir, Nicolas Malebranche, Jean-Paul Sartre, Michel de Montaigne, Voltaire, Denis Diderot, Victor Hugo, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, André Gide, Nikos Kazantzakis, Emanuel Swedenborg, Baruch Spinoza, Desiderius Erasmus,[citation needed] Immanuel Kant, David Hume, René Descartes, Francis Bacon, Thomas Browne, John Milton, John Locke, Nicolaus Copernicus, Niccolò Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei, Blaise Pascal, and Hugo Grotius.