Indian Ocean Dipole

The IOD is one aspect of the general cycle of global climate, interacting with similar phenomena like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in the Pacific Ocean.

[12] A 2009 study by Ummenhofer et al. at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Climate Change Research Centre has demonstrated a significant correlation between the IOD and drought in the southern half of Australia, in particular the south-east.

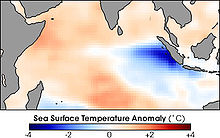

In the IOD-positive phase, the pattern of ocean temperatures is reversed, weakening the winds and reducing the amount of moisture picked up and transported across Australia.

[14][15][16] A positive IOD is linked to higher than average rainfall during the East African Short Rains (EASR) between October and December.

[18] This higher than average rainfall has resulted in a high prevalence of flooding in the countries of Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Somalia and South Sudan.

[20][21][22][23] It is expected that the Western Indian ocean will warm at accelerated rates due to climate change[24][25] leading to an increasing occurrence of positive IODs.

[27] A 2018 study by Hameed et al. at the University of Aizu simulated the impact of a positive IOD event on Pacific surface wind and SST variations.