Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka

They predominantly descend from workers sent during the British Raj from Southern India to Sri Lanka in the 19th and 20th centuries to work in coffee, tea and rubber plantations.

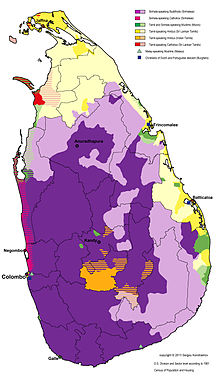

These Tamil speakers mostly live in the central highlands, also known as the Malayakam or Hill Country, yet others are also found in major urban areas and in the Northern Province.

[10] However, the ethnic conflict has led to the growth of a greater sense of common Tamil identity, and the two groups are now more supportive of each other.

According to Professor Bertram Bastianpillai, workers around the Tamil Nadu cities of Thirunelveli, Tiruchi, Madurai and Tanjore were recruited in 1827[13] by Governor Sir Edward Barnes on the request of George Bird, a pioneering planter.

[15] As soon as these migrant workers were brought to Mannar, the port at which they landed on their arrival by boat from South India, they were moved via Kurunegala to camps in the town of Matale.

They joined hands with the Lanka Sama Samaja (or Trotskyist) Party, which carried the message of a working-class struggle for liberation from the exploitation by the mainly-British plantation companies.

According to opposition parties he was also influenced by segments of the majority Sinhalese population who felt their voting strength was diluted due to Indian Tamils.

Although since the introduction of universal franchise in 1931, strong traditions of social welfare in Sri Lanka have given the island very high indicators of physical well-being.

Page 57 of the report proposed: In the first place we consider it very desirable that a qualification of five years residence in the Island (allowing the temporary absence not exceeding eight months in all during the five years period) should be introduced in order that the privilege of voting should be confined to those who have an abiding interest in the country or who may be regarded as permanently settled in the Island... this condition will be of particular importance in its application to the Indian immigrant population.

Governor Stanley, by an order in council introduced restrictions on the citizenship of Indian workers to make the Donoughmore proposals acceptable to the Ceylonese leaders.

Thus the first state council of 1931, which consisted of many Tamil and Sinhalese members, agreed to not to enfranchise the majority of the Indian estate workers.

[18] D. S. Senanayake had led the 1941 talks with Sir G. S. Bajpai of India and had reached agreement on modalities of repatriation and citizenship, although they were finally not ratified by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Although this worried the Kandyans, the main reason for Senanayake and others to review their attitude to Indian workers was the growing threat of Marxist infiltration into estate trade unions.

In this he had won the concurrence of G. G. Ponnambalam for the second citizenship act, which required ten years of residence in the island as a condition for becoming citizens of the new nation.

Senanayake, who had been very favourable to easy citizenship for Indian workers had increasingly modified his views in the face of Marxist trade union activity.

The colonial government responded to the agitation of the leftists by imprisoning N. M. Perera, Colvin R. de Silva and other left leaders.

However, this was in effect a continuation of the older, somewhat harsher status quo of the Indian workers in the 1930s, prior to the Donoughmore constitution, which called for only five years' residence.

[20] As the president of the Ceylon Indian Congress (CIC), S. Thondaman had contested the Nuwara Eliya seat in the 1947 general election and won.

Even at that time, Thondaman was the leader of the Ceylon Workers Congress, the party of the Hill Country Tamils, and had become a skilful player of minority-party politics.

He had avoided joining with the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) resolutions of 1974, which had continued with the policies of the ITAK.

The Sirima-Shastri Pact of 1964 and Indira-Sirimavo supplementary agreement of 1974 paved the way for the repatriation of 600,000 persons of Indian origin to India.

An educated middle class made up of teachers, trade unionists and other professional began to make its appearance.

[11] In 1984–85, to stop India's intervention in Sri Lankan affairs, the UNP government granted citizenship right to all stateless persons.

The late Savumiamoorthy Thondaman was instrumental in using this electoral strength in improvement of the socioeconomic conditions of Hill Country Tamils.

The office adjoins this and these are surrounded by the quarters of the staff members such as clerks, tea makers, conductors, petty accountants or kanakkupillais, and supervisors.

The traditional musical instruments such as thappu and parai are used and folk dances such as the kavadi, kummi and karaga attam are performed.

Furthermore, a minority of the Indian Tamils- 7.6 percent are converts to Christianity, with their own places of worship and separate cultural lives.

Devotees of the plantation sector walk from the tea estates and hometowns they live in to Kathirkamam, a place considered sacred by both Buddhists and Hindus, in the South of Sri Lanka, where Murugan is worshipped in the form of Skanda.

Deities such as Madasamy, Muniandi, Kali, Madurai Veeran, Sangili Karuppan, Vaalraja, Vairavar, Veerabathran, Sudalai Madan, and Roda Mini are also worshipped.

Other NGOs work towards the development of the plantation communities such as Shining Life Children's Trust and Hanguranketha Women's Foundation.