Indian natural history

These studies would today be considered under field of ecology but in former times, such research was undertaken mainly by amateurs, often physicians, civil servants and army officers.

[3] The swamp deer or barasingha was found in Mehrgarh in Baluchistan till 300 BC and probably became locally extinct due to over-hunting and loss of riverine habitat to cultivation.

[4] The Vedas represent some of the oldest historical records available (1500 – 500 BC) and they list the names of nearly 250 kinds of birds besides many other notes on various other fauna and flora.

[6] A notable piece of information mentioned in the Vedas is the knowledge of brood parasitism in the Indian koel, a habit known well ahead of Aristotle (384 – 322 BC).

The first empire to provide a unified political entity in India, the attitude of the Mauryas towards forests, its denizens and fauna in general is of interest.

[13] Another work from this period was Mriga Pakshi Shastra, a treatise on mammals and birds written in the 13th century by a Jain poet, Hamsadeva.

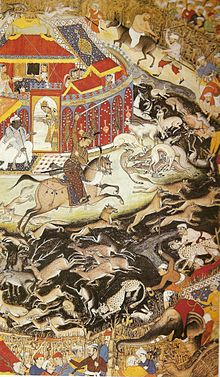

A wolf certainly would not require 20 or 30 arrows to kill it.Ustad Mansur, a 17th-century court artist of Jehangir,[19] was the first man to accurately paint the Siberian crane.

...;and, secondly, that as Great Britain possesses such vast territories in Asia, colonies in Africa and the West Indies, and is now cultivating extensive connections with both North and South America, (not to mention the entire possession of that extensive and interesting country New Holland), a fine opportunity is afforded for forming Collections of rare and beautiful Insects, as well as enriching those already made; and especially as these objects of Natural History are admitted into this country free of all duty.

Many persons, therefore, who have been hitherto deterred from consigning to their friends valuable Collections of Insects, may now gratify them at a trifling cost; and we would anxiously impress upon our readers who may visit or reside in foreign countries, the great importance of attending to this subject, as we are persuaded that some of the choicest Collections in England have received their most rare and novel specimens from such well-timed and pleasing donations.With cabinets of curiosity already popular in European homes, trade and movement of natural history specimens around the world grew with the growth of shipping.

The Indian Civil Services, whose selection procedure included tests in the knowledge of botany, zoology and geology, brought many British naturalists to India.

This was subsequently studied by John Edward Gray (1800–1875) and led to the publication of Illustrations of Indian zoology: chiefly selected from the collection of Major-General Hardwicke and consisted of 202 colour plates.

[26][27][28][29][30][31] A large and growing number of naturalists with an interest in sharing observations led to the founding of the Bombay Natural History Society in 1883.

The work of this generation of geologists led to globally significant discoveries including support for continental drift and the idea of a Gondwana supercontinent.

The whole of this collection, amounting to 60,000 skins, besides a very large number of nests and eggs, has now been presented by Mr. Hume to the British Museum; and as the same building contains the collections of Colonel Sykes, the Marquis of Tweeddale (Viscount Walden), Mr. Gould, and, above all, of Mr. Hodgson, the opportunities now offered for the study of Indian birds in London are far superior to those that have ever been presented to students in India.The famous names in the ornithology of the Indian subcontinent during this era include Several comprehensive works were written by Jerdon, Hume, Marshall and E. C. S. Baker.

Those who joined the Indian Civil Services in later years had access to these works and this period was mostly dominated by their short notes in journals published by organisations such as the BNHS, Asiatic Society and the BOU.

In 1904 Captain Glen Liston of the Indian Medical Service read a paper on Plague, Rats and Fleas in which he noted the lack of information on rodents.

Other notable mammalologists included Richard Lydekker (1849–1915), Robert Armitage Sterndale, Stanley Henry Prater (1890–1960) and Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800–1894).

In 1901 His Highness Sir Prabhu Narani Singh, Bahadur, G.C.I.E., Maharajah of Benares, who promised a supply of Indian elephants when required was elected an Honorary Member of the Society.

Major contributions to the study of species and their distributions were made by Patrick Russell (1726–1805), the father of Indian ophiology, Colonel R. H. Beddome (1830–1911), Frank Wall (1868–1950), Joseph Fayrer (1824–1907) and H. S. Ferguson (1852–1921).

Entomologists who left a mark include William Stephen Atkinson (1820–1876), E. Brunetti (1862–1927), Thomas Bainbrigge Fletcher (1878–1950), Sir George Hampson (1860–1936), H. E. Andrewes (1863–1950), G. M. Henry (1891–1983), Colonel C. T. Bingham (1848–1908), William Monad Crawford (1872–1941), W. H. Evans (1876–1956), Michael Lloyd Ferrar, F. C. Fraser (1880–1963), Harold Maxwell-Lefroy (1877–1925), Frederic Moore (1830–1907), Samarendra Maulik (1881–1950), Lionel de Nicéville (1852–1901), Ronald A. Senior-White ( 1891–1954), Edwin Felix Thomas Atkinson (1840–1890) and Charles Swinhoe (1836–1923).

[44] Numerous officers including James Sykes Gamble (1847–1925), Alexander Gibson and Hugh Francis Cleghorn in the Indian Forest service added information on the flora of India.

Several amateurs also worked alongside from other civil services and they were assisted by professional botanists such as Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817–1911), John Gerard Koenig (1728–1785), Robert Wight (1796–1872),[45] Nathaniel Wallich (1786–1854) and William Roxburgh (1751–1815), the Father of Indian Botany.

A. Dunbar-Brander (Conservator of Forests in the Central Provinces), Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887), Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765–1837), Charles McCann (1899–1980), Hugh Falconer( 1808–1865), Philip Furley Fyson (1877–1947), Lt. Col. Heber Drury, William Griffith (1810–1845), Sir David Prain (1857–1944), J. F. Duthie, P. D. Stracey, Richard Strachey (1817–1908), Thomas Thomson (1817–1878), J. E. Winterbottom, W. Moorcroft and J.F.

Other notable museum curators and workers include Alfred William Alcock (1859–1933), John Anderson (1833–1900), George Albert Boulenger (1858–1937), W. L. Distant (1845–1922), Frederic Henry Gravely (1885–?

), John Gould (1804–1881), Albert C. L. G. Günther (1830–1914), Frank Finn (1868–1932), Charles McFarlane Inglis (1870–1954), Stanley Wells Kemp (1882–1945), James Wood-Mason (1846–1893), Reginald Innes Pocock (1863–1947), Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847–1909), Malcolm A. Smith (1875–1958) and Nathaniel Wallich (1786–1854).

Post independence ornithology was dominated by Salim Ali and his cousin Humayun Abdulali who worked with the Bombay Natural History Society.

Salim Ali worked with American collaborators like Sidney Dillon Ripley and Walter Norman Koelz to produce what is still the most comprehensive handbook of Indian ornithology.

B. S. Haldane, the British scientist who encouraged field biology in India on the basis that it was useful while at the same time requiring low investment unlike other branches of science.

In southern India M. Krishnan who was a pioneering black-and-white wildlife photographer and artist wrote articles on various aspects of natural history in Tamil and English.

Of this newsletter, Horace Alexander wrote:[49] Now, twenty-five years after independence, the delightful Bulletin for Birdwatchers, produced each month by Zafar Futehally is mainly written by Indian ornithologists: and the western names that appear among its contributors are not all British.Wildlife photography has also helped in popularizing natural history.